If any immigrant or native aspires to develop a full understanding of the maddening contradictions that coalesce into the United States of America, and in doing so discover why the country manages to scintillate with the promise of sex, freedom and wealth, even while it horrifies any honest observer with its gluttonous appetite of self-destruction, all that is necessary is to study the triumphant and strange life of Elvis Presley.

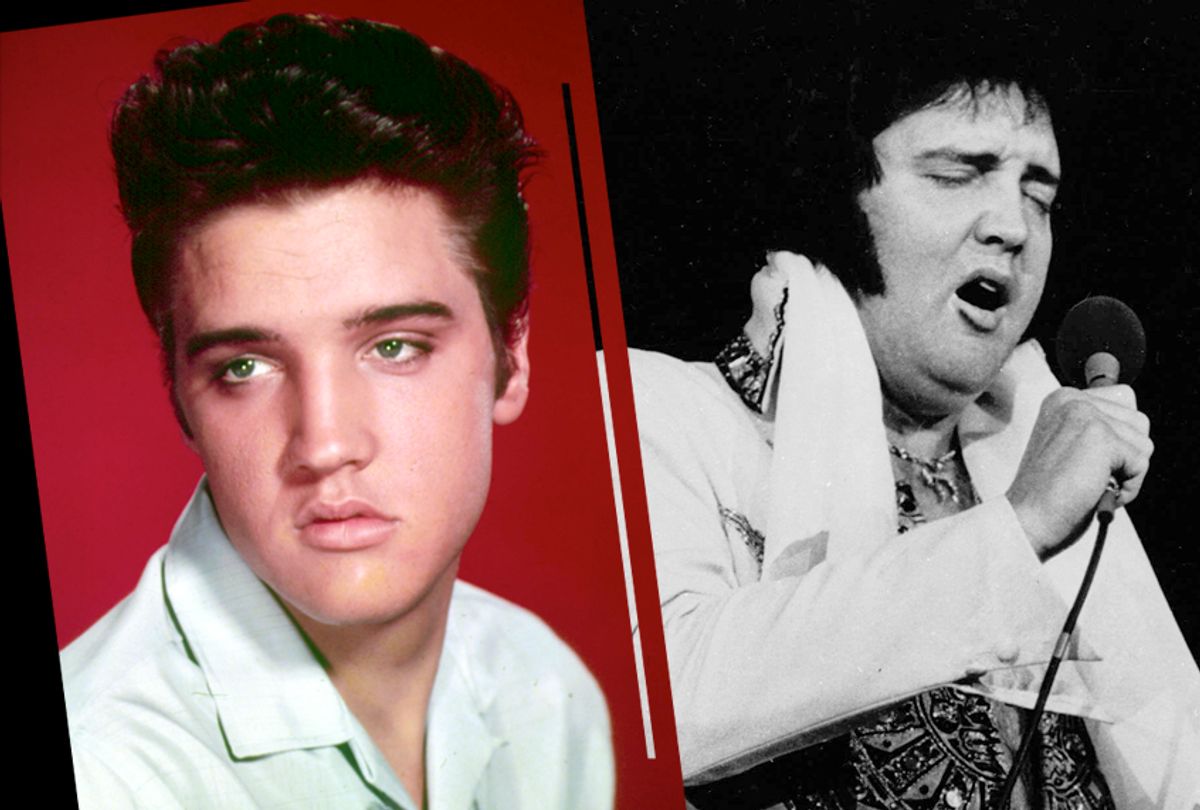

The pompadour, curled lip, and mutton-chop sideburns might have emblazoned themselves into a logo — instantly recognizable but hardly any different, to millions of people, from the golden arches or the red and white of Coca-Cola — but beneath the commercial aesthetic of kitsch beats the heart of an original artist who not only helped to change the world, but in his meteoric rise and Shakespearean fall, captures the best and worst qualities of his country.

Lester Bangs, the legendary rock and roll critic, eulogized Elvis with the declaration, “We will never agree on anything as we agreed on Elvis.”

For all the power of his intellect and might of his pen, the years subsequent to Elvis’ death have battered Bangs’ prediction. Out-of-shape and out-of-key Elvis impostors have frozen Elvis in the imagery of his final days, when he was a shadow of his former self, and in doing so, have encouraged many young people to see him as little more than a bad joke. The Guardian recently reported that young Brits who enjoy the music of their parents’ — or even grandparents’ — generation prefer the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan, not showing much curiosity in the man who inspired all of them.

Many others deride and dismiss Elvis as cultural pickpocket. Michael Eric Dyson charges Presley with “performing a derivative blackness,” while Kiana Fitzgerald, writing for Complex, sees Elvis’ music as nothing more than “watered down black blues.” The urban legend, long ago debunked by Jet magazine and other sources, that Elvis said black people were only good for “buying records and shining shoes” does not help matters.

Those who cite the academic catchphrase “cultural appropriation” expose an ignorance of Elvis’ music. What made his early years sufficiently magical to cast a spell over the youth of the world was the ease with which his songs evaded category. “That’s Alright,” his first hit, featured Elvis playing country-style guitar in the accompaniment of a blues and gospel vocal delivery. He followed up the success of his debut with a rockabilly version of the bluegrass song “Blue Moon of Kentucky.”

“When I was a kid I had records by Hank Williams, Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland, and Mario Lanza,” Elvis once told an interviewer; “I just love music.”

His voice and vision refused to adhere to the boundaries of any genre. The music emanating out of his heart and lungs was a homebrewed elixir. Ingredients he found in the black churches and blues clubs of Memphis were no more or no less important than those he collected from the country radio stations, barn dances and white churches in Mississippi.

Elvis is America because, contrary to kitsch, he is an avatar of individuality and diversity. He was a white hillbilly with a black influence, a sexual pioneer who was deeply religious, a comfortable inhabitant of the Southern fields and neon-lit city streets, an icon of masculine charisma who wore pink pants and eyeliner — unembarrassed, even in the 1950s, to display effeminacy.

He channeled the complexity and multiplicity of his experiences — from growing up dirt poor in Tupelo to sneaking into the clubs on Beale Street — into a creative energy allowing him to explore the diverse terrain of American music. He sang country, blues, folk, funk, black gospel, white gospel and rock and roll.

A new documentary premiering April 14 on HBO, appropriately titled "The Searcher," shows Elvis as musical explorer, and demonstrates what too many fans and critics have forgotten. He was not only one of America’s great singers, but also an “inventive” — to use BB King’s word — arranger and interpreter.

Elvis’ search for the “right sound,” as he once put it, symbolized creative excellence, but also freedom to an entire generation of people. If he felt like copying the dance moves he learned from a stripper on national television, he did. If he felt like singing “Peace in the Valley” as a tribute to his mother on the same program, he did. Bob Dylan said that the first time he heard Elvis, he felt like he had just “busted out of jail.” When teenagers in East Berlin protested against the shackles of Soviet authority, they carried placards and chanted his name — not George Washington or John Kennedy, but Elvis.

Walt Whitman said that America, because of its freedom and diversity, was a “new nation in need of new poets.” Not even a songwriter, Elvis became one of those poets — a man of multitudes who freely contradicted himself. Just as the American revolution inspired many subsequent revolutions, so did Elvis have many disciples and children.

Following the Civil War, Whitman’s enthusiasm waned. He wrote with worry that “genuine belief” had left America, and openly wondered if Americans were unfit for the heavy lifting of democracy.

If Bangs was correct in pointing out the universality of appreciation for Elvis in the 1950s, 1960s — even with all the bad movies — and early 1970s, when Elvis led the first international satellite broadcast, the "Aloha from Hawaii" concert, to become one of the most watched events in the history of television, on what could people agree about Elvis in 1977, the year of his death?

Elvis was bloated, drug addled, and despite flashes of brilliance on stage, unable to hit the high notes. A victim of his own ego and excess, he lived a lonely life within a fortress of self-containment. The gates of Graceland, originally meant to protect him from interlopers -- including Jerry Lee Lewis, who crashed his car into the entrance, and Bruce Springsteen, who climbed the fence in an attempt meet his hero -- had become the doors of a self-guarded prison.

Elvis died a sad mutation of his former self — unhappy and largely alone, finally crumbling in the toxic war he waged against his own body. As trust in its institutions crashes, and its people become increasingly isolated, so too does America tempt a dark fate.

With Donald Trump as president, Elvis’ tragic demise doubles as a cautionary tale for a country obsessed with material gain over all else, and too closed-minded to reconceive of itself and adjust to a rapidly changing world.

America now appears as Elvis did -- not at the beginning, when he became a rags to riches musical innovator and symbol of erotic and creative possibility, but at the end, when he worried his friends and alienated others with his descent into odd ideas and poor health.

Unlike America, however, “genuine belief” never left Elvis. Even in his final days, he continued to sing with passion and demonstrate the power of the promise of union. Elvis believed in bridges and not barriers. Far from building them, with every note, smirk, and shake of the hips, he tore down walls.

One of the tragic elements of Elvis’ end is that he still had great potential for further stages in his career. His last recordings, collected on the recent box set "Way Down in the Jungle Room," are full of amazing moments and performances. He didn’t have to, but he succumbed to addiction and loneliness.

Will America fall, “slumped against the drain with a whole lotta trouble running through its veins,” as Springsteen sang about Elvis in his song, “Johnny Bye Bye” or is it preparing to emerge for an encore?

One of Elvis’ most triumphant moments was his closing number to the marvelous 1968 Comeback Special. With the Vietnam War and race riots creating death and destruction at home and abroad, Elvis, in a white suit, chose to sing “If I Can Dream.” Written by Walter Earl Brown and inspired by Martin Luther King, the song acts as a prayer for peace, justice, and universal brother- and sisterhood.

Just two months after King’s assassination, which a girlfriend claims had Elvis weeping and singing hymns all night, Elvis thundered the words:

We're lost in a cloud

With too much rain

We're trapped in a world

That's troubled with pain

But as long as a man

Has the strength to dream

He can redeem his soul and fly

Forty-one years after his death, America cannot escape Elvis, because in our highest hopes and purest ambition, but also our saddest stumbles along the roads of missed opportunities, we are Elvis.

The dream is still alive. Will it come ever true?

Shares