“I know we can’t bridge it, but how do we help make it better?”

That’s how journalist Salena Zito posed the question of how to approach a public reckoning with the ever-increasing ideological and cultural split between progressive metropolitan areas and conservative small-town America — as a malady of modern society without a solution.

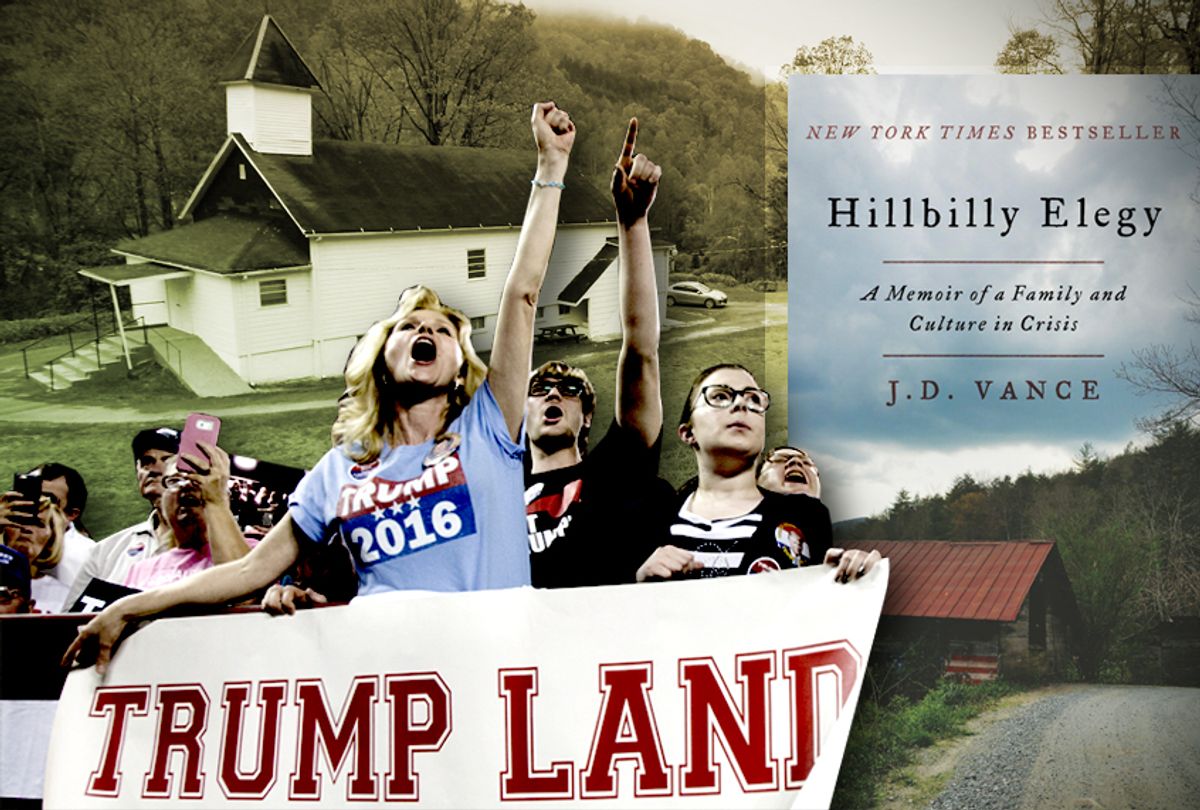

The veteran reporter and political analyst sat down in conversation with author J. D. Vance last week at an event in Raleigh, North Carolina entitled Hillbilly Elegy and the Urban-Rural Divide. The event was hosted by the Carolina Partnership for Reform, a public benefit think tank focused on research and education about conservative policy reforms. (The organization mostly takes the form of a blog and sparse Twitter feed run by longtime Republican operatives Robert Harris and Jeff Hyde.)

The night’s discussion was ostensibly about policy-oriented solutions that bridge differences in public opinion across urban and rural areas, yet the conversation offered little in the way of tangible action. Instead, the two speakers focused on their personal experiences overcoming the circumstances of their birth and musing on how and why popular sentiments have shifted over the course of their lifetimes.

One potential thread the two identified in navigating this territory: a sort of causal relationship between the decades-long decline in church-going nationwide and how television programs portray the American people.

“It’s pretty remarkable how much of a disconnect there is between basic lived experiences of people of faith and what you see in the media,” Vance said on stage. He said he worries that politics have become “a sort of civic religion.”

He recalled a conversation with a senior Obama official who described the president’s farewell address as having the emotional weight of a tent revival.

“If a farewell address has the feel of a religious ceremony, then who is God in that story?” he said. “That just really, really worries me — that the focus on and the importance of politics is becoming people’s identity.”

Both expressed fear about not only the implications this has for our country’s morality, but what may be replacing religious institutions and other cultural touchstones. A newly emboldened focus on American individualism makes us insular — if everything is political, he argued, we’re losing the spaces where we don’t have to be scared of our difference.

Vance called this trend “new,” “unique” and “troubling.”

But most scholars suggest that the history of bitterly divisive political discourse in America is not a new phenomena, but an essential feature in the democratic process, symptomatic of periods of profound social change – like the Civil War, the Industrial Revolution or the present digital and cultural disruptions. Susan Herbst, author of "Rude Democracy: Civility and Incivility in American Politics" argues that polarization, negativity and even rudeness are natural byproducts of conflict resolution in democracies. However, Zito and Vance argue that religion is the essential ingredient missing in the common glue that binds us.

A primary cause for this all-encompassing polarization, Zito said, is that churches don’t serve as our primary community centers anymore — suggesting that high school sports and Narcotics Anonymous meetings have replaced them in Appalachia.

While their argument about the profound loss of community and tradition resonates across the political spectrum, simplistic solutions based entirely on an ethos of individual choice obscure the historical consequences of unbridled extractive capitalism on the health of the individuals, families and communities of Appalachia.

What they’re talking about is social capital — the mutual trust and codependency that results from an interdependent web of civic engagements. This human potential is part of what makes all societies, but particularly democracies, work effectively. By tapping into these connections, Americans have historically enacted change through of the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness.

Vance is nearly right in lamenting the disappearance of the structure of the community church — the concept best exemplified through the revolutionary roles of institutions like the Black church in the civil rights movement or women’s social groups on the issue of suffrage.

But social capital is fueled by empathy, compassion, justice, trust and cooperative effort. It’s counter to the stifling self-interest that implies a stint in the military and a tug on the bootstraps are all that’s needed to dig one’s way out of a cycle of generations of circumstantial decisions. Circumstances often dictated by distant, powerful economic entities with few ties to local community, and interests focused on extracting short-term economic gain, not long-term investment in sustainable community institutions.

Throughout the country’s history, it is this distinct nuance of individualism over self-interest that seems to play the biggest role in democracy as a governmental function — i.e., motivation towards actually bridging divides through shared policy decisions.

The danger with subjectivity, though, is that lack of interest in the general public (others) can lead to apathy, and without public involvement a democracy has no guidance. As modern sociologists agree, a successful democracy depends on a public that is informed about the issues, aware of the ways in which they are discussed, and regularly debates those issues of the day.

In other words, people need to talk about current events in this social capacity, outside of the binary partisan arena of politics and in contexts where they can see themselves and their communities in order to better understand their own participation in society. Meaning: yes, technically the new politics of the recent Roseanne reboot are actually good for us, but not for the reasons Zito and Vance argue.

Zito cited that the top 20 markets for the new Roseanne show included places like Oklahoma, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh — New York and Los Angeles didn’t make the cut. Folks are watching characters that look like themselves.

“The reaction shouldn’t be 92 different kinds of Roseanne shows,” Zito said. “But it should be a recognition that you show middle class people in a more respectful and authentic way.”

Vance said he hasn’t seen the show yet, but he agrees with sentiment he has seen online that mainstream political discourse needs spaces that show political disagreements that aren’t the entirety of someone’s political identity.

To that way of thinking, Elizabeth Catte, author of “What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia,” offered a relevant criticism of Vance’s “Hillbilly Elegy” in an interview with Salon:

“I think it is aligned with his eagerness to deploy certain conservative politics and certain conservative outlooks. It kills me that this is a book that liberals, in particular, and college-educated people think, ‘Well, he set his politics aside just to write from the heart.’ They don’t understand, or perhaps they do and they dismiss it, but blaming poverty on poor people is a political opinion.”

Therein lies the fundamental mark that these commentators keep missing: we actually do need 92 different Roseanne’s. We need to see ourselves in our media. In Appalachia especially, we need to tell stories outside of the lens of “Hillbilly Elegy” and outside too of Elizabeth Catte’s worldview.

To bridge the divide is to engage in a public conversation with room for the lived experiences of folks faced with similar struggles, and listening to how they came to a different conclusion — reveling in these differences and mediating guilt and self-interest into productive, fruitful and functional conversation in our daily lives. The “problem” cannot be solved by way of a forced return to family values, church attendance or a monolithic narrative of middle America. The way forward starts with incremental, daily work within the communities in which we already find ourselves.

Lovey Cooper (@loveycooper) is a contributing editor with 100 Days in Appalachia, reporting on the intersection of politics and culture. Her work appears in The Atlantic, Vice, Rewire.News, Education Week and more.

Shares