On February 20, 1998, Yahoo! Launch ran a piece about Elliott Smith's Oscar nomination–one of the first to appear anywhere in the mainstream media. Discussing Smith's contributions to Gus Van Sant's popular Hollywood film, the article's writer retroactively constructs a "star image" for Smith via the "narrative image" of Matt Damon's Will Hunting:

Maybe [Smith and Will Hunting] aren't so far apart; maybe Elliott Smith was so perfect for "Good Will Hunting" because, just like Will in the movie, while seen by society as a f**k-up, he's a genius working in obscurity who's suddenly given the chance to enter the mainstream. That is, if he can . . . and if he wants to.

A number of assumptions are passively enacted here; most notably, that Smith is "seen by society as a f**k-up." Who exactly sees Smith as a f**k-up is not specified—the narrative of Smith's meteoric and unprecedented ascent is, in a sense, already written: just as Sean Maguire acknowledged and elevated Will Hunting's scorned and untapped genius, we can all acknowledge and elevate Elliott Smith's. The problem, of course, is that Smith's genius was not all that untapped, nor his ascent all that meteoric or unprecedented. By and large, "society" didn't see Elliott Smith at all, and among those who did, he was well respected for his musical talent. Having already released an album on one major label and signed a contract with another, any claim to Smith's absolute "obscurity” is more than a little bit dubious. But the story of the unrecognized, "authentic” genius suddenly thrust into the national spotlight is an irresistible one.

On March 20, 1998, this "authentic genius" was introduced to the country at large; Smith was written up in an extensive USA Today article that reads as a kind of primer on the deferrals and paradoxes inherent to Smith's cultural positioning. As with the Yahoo! Launch piece, it introduces Smith as a singer "plucked out of obscurity and plunked smack into Oscar hubbub." The article goes on to say that Smith “has been described as an acerbic poet and street bohemian who writes sad folk songs." Smith's self-description as "pop . . . I like melodies" does little to drown out the unspecified throngs who apparently perceive him as an "acerbic poet.” Once again, an uncredited passive voice is used to describe Smith to an audience that is likely quite unfamiliar with his work. Needless to say, I have not been able to find a single article that explicitly names Smith as a “street bohemian."

An April 1998 article in the LA Times expounded a bit upon what exactly the life of a newly elevated "street bohemian" might look like:

A few weeks ago, Elliott Smith performed his Oscar-nominated song "Miss Misery" for more than 55 million on the Academy Awards telecast. A month earlier, he was playing the tiny L.A. Rock club Spaceland. A year ago he was trying to kill himself.

Here again, Smith's "authenticity" is posed as a direct counterpoint to the inauthentic Academy Awards. And, as would often be the case, allusions to suicide attempts–or heroin use–are offered as irrefutable proof of such authenticity. (Both of these subjects have long been used as rhetorical shortcuts to "authenticity" for many artists, writers, and musicians.) Doubtless, the fact that Smith broached these subjects in his lyrics made it all the more necessary for suicide and drug abuse to be constructed as an integral part of his life story, as his status as an “authentic" singer-songwriter was predicated upon his musical expression being "real" and "genuine." Besides, if the aestheticization and idolization of a singer's image–like that of Celine Dion–render an artist shallow and false, then what could be more "authentic" than utter self-annihilation?

In her article “Art Versus Commerce: Deconstructing a (Useful) Romantic Illusion," Deena Weinstein suggests that drug use and suicide are common discursive tools for constructing the romantic myth of the artist:

Critics celebrate romantic rock deaths because they affirm the myth of the artist. A drug overdose, a shotgun suicide, or a gangland gangsta slaying; these deaths show, rhetorically, that the romantic artist was authentic, not merely assuming a (Christlike) pose. The right kind of death is the most powerful authenticity effect, the indefeasible outward sign of inward grace. "The artist must be sacrificed to their art; like the bees they must put their lives into the sting they give," Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote . . . Death isn't the only authenticity effect embraced by rock writers. They also champion heroin-addicted musicians and rockers who are off their rockers . . . Addicts and insane are automatically authentic because their grip on rationality is too weak to allow them to "sell out."

Thus, in the wake of his Oscar performance, Smith's "star image," as articulated in the news media, was that of the sad, suicidal sap, suddenly (and perhaps unwantedly) thrust into the national spotlight. His extensive back catalog, its enthusiastic reception, and its modest commercial success often get entirely omitted. Reputable labels (Kill Rock Stars) and sizeable clubs (Spaceland) are suddenly "tiny." And—most troubling of all—Smith himself is positioned as a suicidal "f**k-up," whose "sudden" success as a musician is in no way the result of hard work, perseverance or–God forbid–ambition (I mean, the guy tried to kill himself!).

As Ellis suggested, however, such "star images" are incomplete without that star's texts. In both the Yahoo! Launch and LA Times pieces, "Good Will Hunting" itself is positioned as such a text. The May 30, 1998 UK release of "Either/Or" offered a preliminary glimpse of how Smith's music would be read against his newfound popular construction. A column in the UK's Times includes a near-hallucinatory reading of Smith's music, and its positioning against the "hysterical" artifice of Celine Dion:

You just don't meet Oscar-nominated songwriters who aren't Celine Dion. And, unlike Dion, her 17 producers and her hysterical 1,600-piece orchestra, “Miss Misery," like all Smith songs, is just Smith and his guitar. Finger-picked Nick Drake melancholia. Vague country-folk, washed in inky blue blues, like Simon and Garfunkel trying to be Big Stars.

The equation of Smith's music with "Nick Drake melancholia”—ostensibly in a review of an album thick with electric guitar, bass, drum, and keyboards— seems rooted in more in Smith's popular construction as a Nick Drake-esque folk antihero than in the music itself. A review in the London Independent tows a similar line, opening with a picture of Celine Dion and Smith standing side-by-side at the Academy Awards: "the glittery, coiffured diva and the nervous, slowly spoken singer who etched out his career playing in the quirky and eclectic underground scene of Portland, Oregon.” Once again, Nick Drake is invoked as a point of reference:

For someone who delivers haunting tales of truncated, druggy relationships set to a mostly acoustic soundscape and delivered in fragile whispering tones, Smith's rave notices in the US press have often harked on about Nick Drake or other folk or singer-songwriting legends. It's not something he seems to cherish.

This curiously anthropological-sounding observation ushers in an extensive quote from Smith, explaining that he is "neither folk nor singer-songwriter," and that he's always had a preference for "punk bands."

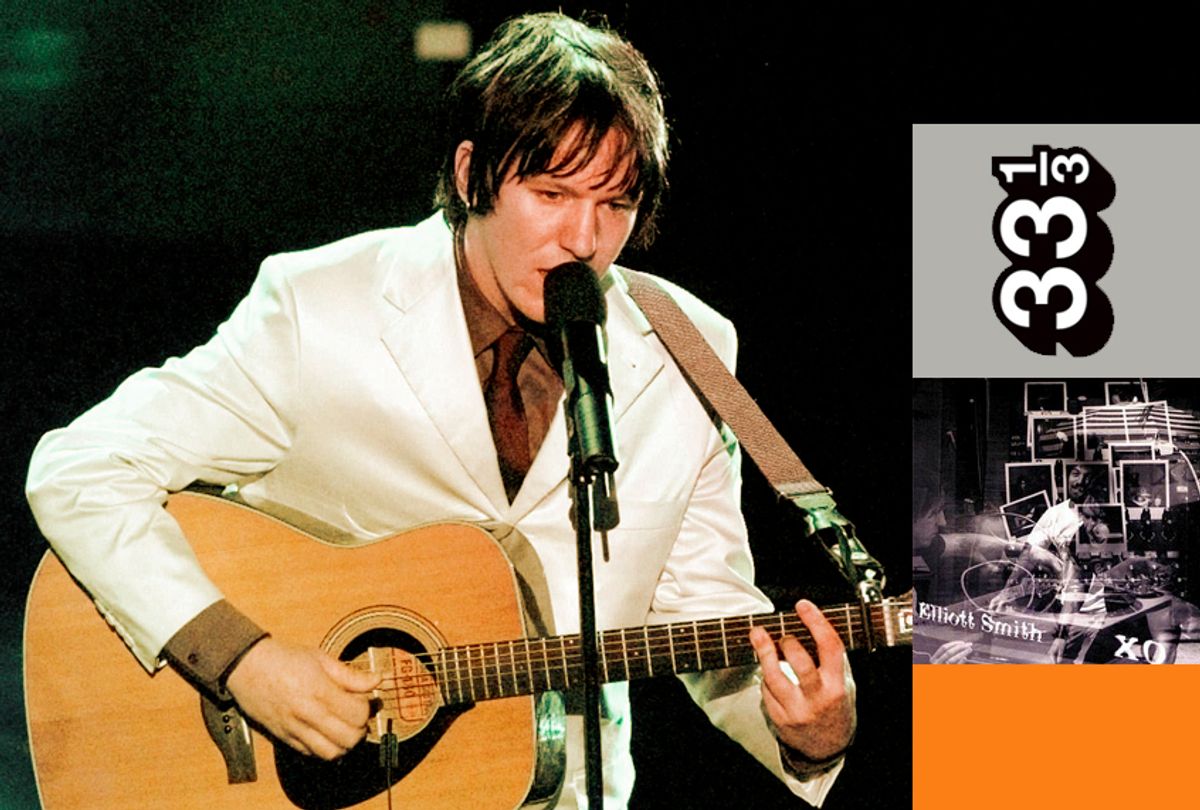

Excerpted from "Elliott Smith's XO" by Matthew LeMay (Continuum, 2009). Reprinted with permission from Bloomsbury Publishing.

Shares