RCA Records made a radio spot for the release of "Transformer" that may have been amusing, disturbing or both to Reed. Over a medley of the most hard-rocking moments of the album, the announcer reads: “In the midst of all the make-believe madness, the mock depravity and the pseudo-sexual anarchists, Lou Reed is the real thing. Lou Reed: the original. He’s been one since the birth of the New York underground, and now he’s back with a new album: 'Transformer.'”

So Reed is advertised as honest, as opposed to all the phonies. In the process of capitalizing on his “real”-ness, he reaches an apex of phoniness which he will never match in all his career. Bowie, whether to his credit or discredit, took him there.

Together, they present an alternative to the future of rock music a million miles away from the likes of Three Dog Night. As music critic Ken Tucker put it: “In the face of the hippie era’s sincerity, intimacy and generosity, Bowie presented irony, distance and self-absorption.” In an era where nobody trusts anyone they hear on the radio or see on TV, it was refreshing to find someone who wasn’t pretending to be just like the regular folks in the audience.

Throughout his career Bowie aims to create distance between himself and his work, between himself and his audience. This is an aspect he noticed immediately in the Velvet Underground, and part of what made hearing them such a sea change moment for him. “The music [on "The Velvet Underground & Nico"] was savagely indifferent to my feelings,” he wrote in New York Magazine in 2003. “It didn’t care if I liked it or not. It could give a f**k.” But this distance from and indifference to the audience, which came so naturally to Lou Reed, became, in Bowie’s hands, a gateway to a pure artifice that had nothing to do with the Velvet Underground’s plainspoken, tough prose-poetry. Bowie wanted distance so he could create a fantasy, an artificial icon with the power to transfigure culture and make it less boring. Lou’s version of distance from the audience is understatement and lack of affect while he tells, essentially, the truth about himself and the world around him. Where Bowie wants to create his own dystopian world, Reed wants to shine a light on the dark places of the real one.

One might agree with what the RCA radio ad suggests: Bowie is a phony and Reed is authentic. This would be to overlook Reed’s dodgy, noncommittal career path as well as Bowie’s stunning moments of earned emotional sincerity. But if Bowie is one of the “pseudo-sexual anarchists” and Reed is “the real thing,” keep in mind that that doesn’t necessarily tell you which one of them makes better records.

This core difference between the two artists is thrown into stark relief when questions of queerness come up. Here’s David Bowie talking to NPR’s Terry Gross in 2002:

GROSS: So did you see the kind of gender aspects of your performance, you know, dressing—you know, sometimes wearing an evening gown, sometimes, you know—often wearing lipstick, dyeing your hair, lots of eye makeup. Did you see the gender stuff as being a statement about postmodernism or a statement about sexuality?

BOWIE: Well, neither—I think they were just devices to create this new distancing from the subject matter.

Bowie, as he has confessed more explicitly elsewhere, was faking his bisexuality and gender ambiguity. Reed was not. But as for showy femininity—makeup, glitter, etc.—that was pretty much a stage persona for both artists, one which, for Lou, clearly didn’t stick. A year later he’s looking pretty much masculine again, as he did in the sixties. He didn’t need a device to create distance. For one thing, sounding (and being) emotionally distant is his specialty; for another, his artistic goal is honesty, not artifice. In many ways, Lou Reed is fighting against his automatic tendency to dissemble. Most of his career is a quest to write a straightforward, three-chord song that tells the plain truth. And for that kind of an artist, Bowie’s theatrical version of rock is an uncomfortable fit.

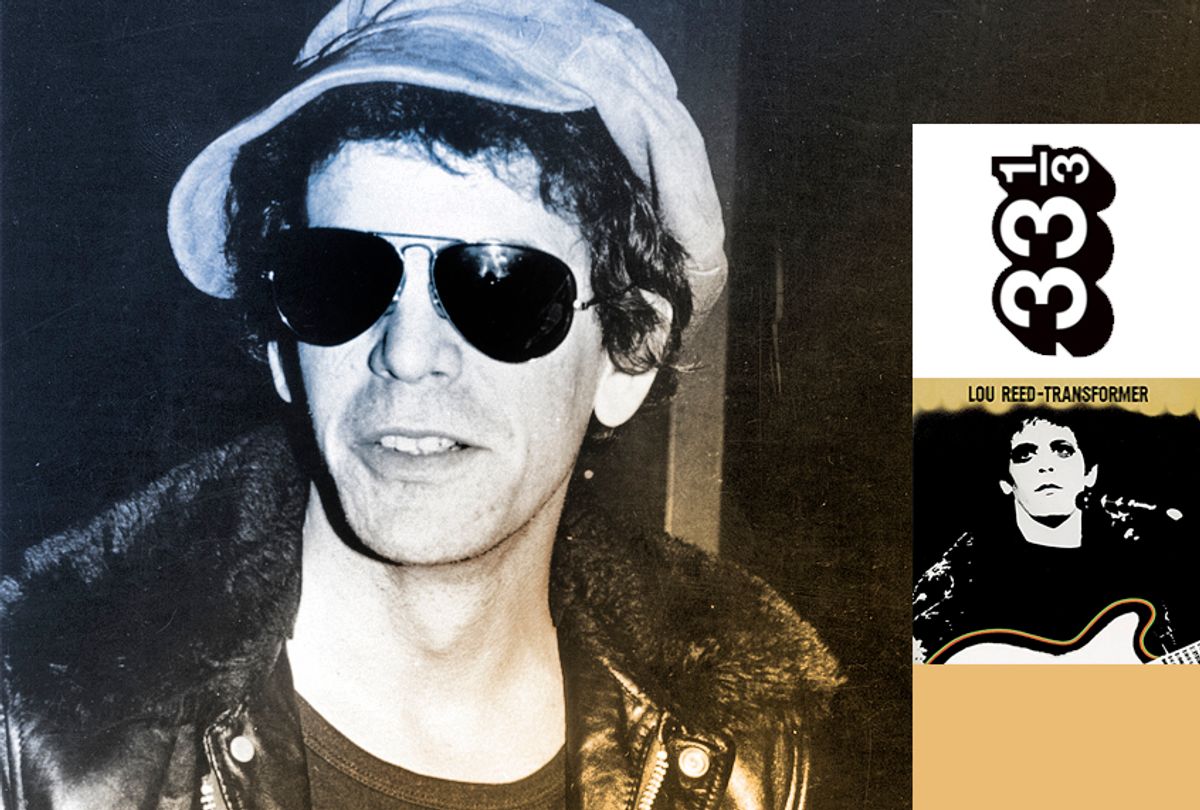

The Bowie superstar machine took Lou Reed and made him into an icon, amplifying and distorting him. What became famous was a stylized snapshot of Lou, not the man himself. It becomes almost impossible to pin down who the real Lou Reed is because, at least on "Transformer," he’s not cast as himself. He’s cast to play the pop culture version of himself, the Lou Reed his fans have imagined was behind his earlier records.

Admittedly, this is part of what celebrity is: turning a person into a symbol. Both Bowie and Reed appreciate this kind of iconography; after all, they’re both admirers of Andy Warhol. “I’d like to be a gallery / put you all inside my show,” Bowie sings in “Andy Warhol” (1971). “Andy Warhol looks a scream / Hang him on my wall.” To Bowie, Warhol represents the dehumanization of the artist into art piece, into celebrity icon. Warhol repurposed and distorted Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe into his material; Bowie used Andy Warhol, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed.

Lou Reed, of course, was an eager collaborator in this move, but dropped hints all along that he was conflicted about it, even in the songs themselves. If the album seems uneven or half-hearted, this is why: because the singer, watching himself move further than ever before into the artifice of celebrity, is not entirely sure he even wants to go through with it.

After "Transformer," Reed is left with the fallout of becoming a rock ’n’ roll symbol along with the dividends. He will be rich and famous. But he’ll also be plagued for the rest of his career by nosy and tone-deaf journalists, moronic fans, cheap imitators, and the impossible task of managing how the pop culture world sees him. “Watch me turn into Lou Reed before your very eyes!” he mocks on the epic rambling version of “Walk on the Wild Side” from 1978’s "Live: Take No Prisoners." “I do Lou Reed better than anybody so I thought I’d get in on it.” It’s the sound of an artist alienated from his famous persona and its uncontrollable mutations in a scene and ascendant genre he influenced more than anyone—and thus, one he can’t resist getting in on. Again he’s doing an imitation of an imitation of himself. But the real thing, in fleeting moments, still shines through.

Excerpted from "Lou Reed's Transformer" by Ezra Furman (Bloomsbury, 2018). Reprinted with permission from Bloomsbury Publishing.

Shares