To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here.

Teachers in red-state America are hard at work teaching us all a lesson. The American mythos has always rested on a belief that this country was born out of a kind of immaculate conception, that the New World came into being and has forever after been preserved as a land without the class hierarchies and conflicts that so disfigured Europe.

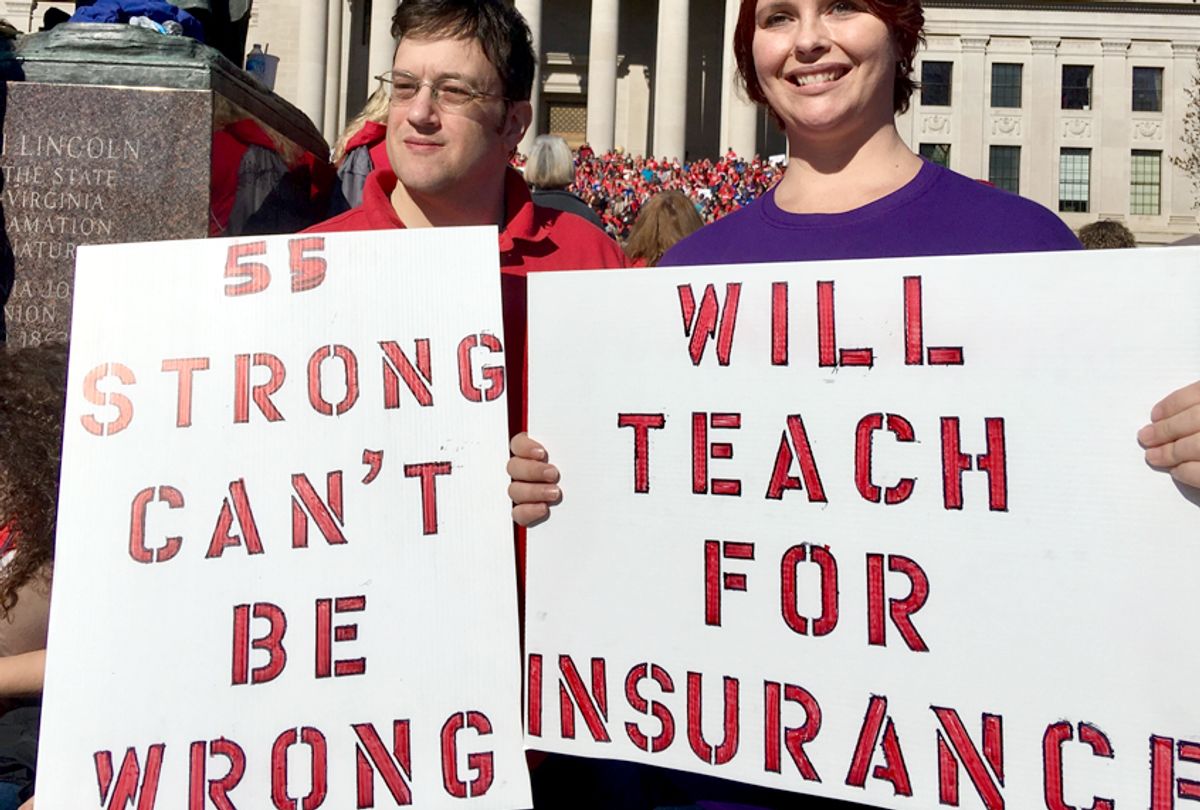

The strikes, rallies, and walkouts of public school teachers in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, soon perhaps Arizona, and elsewhere are a stunning reminder that class has always mattered far more in our public and private lives than our origin story would allow. Insurgent teachers are instructing us all about a tale of denial for which we’ve paid a heavy price.

Professionals or Proletarians?

Are teachers professionals, proletarians, or both? One symptom of our pathological denial of class realities is that we are accustomed to thinking of teachers as “middle class.” Certainly, their professional bona fides should entitle them to that social station. After all, middle class is the part of the social geography that we imagine as the aspirational homing grounds for good citizens of every sort, a place so all-embracing that it effaces signs of rank, order, and power. The middle class is that class so universal that it’s really no class at all.

School teachers, however, have always been working-class stiffs. For a long time, they were also mainly women who would have instantly recognized the insecurities, struggles to get by, and low public esteem that plague today’s embattled teachers.

The women educators of yesteryear may have thought of their work as a profession or a “calling,” subject to its own code of ethics and standards of excellence, as well as an intellectual pursuit and social service. But whatever they thought about themselves, they had no ability to convince public authorities to pay attention to such aspirations (and they didn’t). As “women’s work,” school teaching done by “school marms” occupied an inherently low position in a putatively class-free America.

What finally lent weight to the incipient professional ideals of public school teachers was, ironically, their unionization; that is, their self-identification as a constituent part of the working class. The struggle to create teacher unions was one of the less heralded breakthroughs of the 1960s and early 1970s. A risky undertaking, involving much self-sacrifice and militancy, it was met with belligerent resistance by political elites everywhere. When victory finally came, it led to considerable improvements in the material conditions of a chronically underpaid part of the labor force. Perhaps no less important, for the first time it institutionalized the long-held desire of teachers for some respect, a desire embodied in tenure systems and other forms of professional recognition and protection.

Those hard-won teachers’ unions also paved the way for the large-scale organization of government workers of every sort. That was yet another world at odds with itself: largely white collar and well educated, with a powerful sense of professionalism, yet long mistreated, badly underpaid, and remarkably powerless, as if its denizens were… well, real life proletarians (which, of course, was exactly what they were).

Rebellion in the Land of Acquiescence and Austerity

Despite their past history of working-class rebelliousness, the sight of teachers striking (and sometimes even breaking the law to do so) still has a remarkable ability to shock the rest of us. Somehow, it just doesn’t fit the image, still so strong, of the mild-mannered, middle-class, law-abiding professionals that public school teachers are supposed to be.

What drives that shock even deeper is where all this uproar is happening. After all, for decades those “red states” have been the lands of acquiescence to the rule of big money and its political enablers. The state of Oklahoma, for example, had a legislature so craven, so slavishly in the service of the Koch brothers and the oil industry, that it prohibited the people’s representatives by law from passing new taxes with anything but a legislative supermajority. (A simple majority was, of course, perfectly sufficient when it came to cutting taxes.)

Arizona typically has had a "right-to-work" law since 1947 to fend off attempts to organize workers. Such laws are, in fact, a grotesque misnomer. Rather than guaranteeing employment, they ban unions from negotiating contracts requiring that all workers who benefit from the contract become members of the union and contribute dues to cover the costs of their representation. In all these states, teachers (along with other public employees) are prohibited or severely limited by law from striking.

Such concerted and contagious insurgency in the homelands of the bended knee was unimaginable… until, of course, it happened. Both acquiescence and the current explosive wave of resistance from teachers were the wages of austerity. Those particular Republican-run states were hardly the only ones to cut social services to the bone while muscling up on giveaways to corporate powerbrokers. (Plenty of Democrat-run state governments did the same.) But the abysmal conditions of public schools and the people who work in them in those states have made them the poster children for an age of austerity that’s lasted decades.

Oklahoma, for instance, cut funding per student by 30% over the past 10 years and led the nation when it came to education cutbacks since the 2008 recession. Meanwhile, Arizona has spent less per student than any other state. And that’s just to start down a list of red-state austerity measures in education. The nitty gritty result of such slash-and-burn tactics has meant classes with outdated textbooks, antiquated computers (if any at all), schoolhouses without heat, and sometimes even a four-day version of the usual five-day school week.

West Virginia’s teachers, the first to go out on strike, averaged salaries of $45,240 in 2016, which ranked them 47th in the nation in teacher pay. At $41,000, Oklahoma is even worse. Arizona’s teachers, now threatening to join the strike lines, are 43rd, while Kentucky does only a bit better at $52,000. At some point — always impossible to predict no matter how inevitable it may seem in hindsight — enough proved enough.

Austerity is a politics of class overlordship, or (as we tend to say these days) the dominion of the 1%. It entails, however, far more than just the starving of the public sector, especially education. Those teacher’s salaries and the grim conditions of the deprived schools that go with them are just the budgetary expression of a deeper process of ruthless economic underdevelopment and cultural cruelty.

After all, over the last generation, the deindustrialization of America has paid handsome dividends to financiers, merger and acquisition speculators, junk bond traders, and corporations fleeing a unionized work force for the sweated labor of the global South. In the process, deindustrialization ravaged the economic and social landscape of working-class communities (including that of red-state teachers), turned whole cities into ghost towns, leaving millions on the down escalator of social mobility, and made opioids the dietary staple of the country’s rural and urban hinterlands.

In the process, deindustrialization dried up sources of industry-based tax revenues which had once helped maintain a modicum of social services, including ones as basic as public education. Tax givebacks, subsidies, or exemptions for the business world grew lush as roads, bridges, public transport, health care, and classrooms deteriorated.

Blaming the Victims

Scapegoats for this unfolding disaster were rounded up — the usual suspects, of course: the inherent laziness of the desperately poor and immigrants, all living off the public weal; liberal sentimentalists manning the welfare state; greedy unionized workers undermining American competitiveness; and above all, the racially disfavored.

Oh yes, and there was one extra, far more surprising miscreant in that line-up: those otherwise quintessentially respectable, law-abiding professionals teaching our kids. If those children failed to measure up, if they couldn’t read or write or do math, if they were scientific illiterates, if they grew up black or “undocumented” distrusting official authority, if they dropped out or were drugged out, if they seemed to exhibit an all-sided dysfunction and ill-discipline, it had to be the fault of their teachers. After all, they had cushy jobs, went home at three, had their summers off, and enjoyed immunity from public oversight thanks to their all-too-powerful unions.

Acquiescence and austerity breed cultural decline, a telling sign of which has been the blaming of teachers for a profound, many-sided social breakdown they were largely the brunt of, not the cause of. A country undergoing systemic underdevelopment like the United States can’t provide decent housing or health care, a non-toxic environment or reasonable child care, color-blind justice or well-equipped schoolhouses, no less rewarding work. The classroom inherits all those deficits.

Millions of children arrive at school burdened by the costs of secular decline before they ever enter their first class. Teachers try to cope, often heroically, but it’s a losing battle and they get stigmatized for the defeat. It matters not at all that many of them, like those staffing the school systems of West Virginia or Oklahoma, spend innumerable hours beyond the “normal” school day prepping and inventing ways to treat the wounds of social meanness. They even draw on their own spare resources to make up for yawning gaps in books, computers, paper (and not just notebook paper, but toilet paper) that state and local governments have refused to provide funds for.

In those children and those schools can be seen a vision of our society’s future and clearly it doesn’t work. Like so much else about American life of late, this is a world of “winners” and “losers” — and the kids, as well as the teachers, have been on the wrong side of that equation for far too long now.

How convenient it is for the powers-that-be to depict the striking teachers as the problem, as the “losers,” while whittling away at their salaries, supplies, tenure arrangements, and other union protections (when they’re fortunate enough to even have unions), while lengthening teaching hours, reducing vital prep periods, and subjecting them to the discipline of teaching to the test. Just to make ends meet, teachers in those red states often have to moonlight as waitresses or car-service drivers. In a word, until the recent strikes and walk-outs, they had been turned into powerless rather than empowered proletarians.

If Not Now, When?

Punishing and demoralizing as this regime has been, the teachers stood up. Though the urge to write “finally stood up” is there, no one should underestimate the courage and desperation it takes to do just that. Moreover, this moment of resistance to an American world of austerity overseen by plutocrats is not as surprising as it might seem.

We live in the era of both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. In their starkly different ways each of them is symptomatic of our moment — in Trump’s case of a pathological condition, in Sanders’s of the possibility of recovery from the disease of acquiescence and austerity. In both, you can see the established order losing its grip. Even before the Sanders campaign, there were signs that the winds were shifting, most dramatically in the Occupy Wall Street uprising (however short-lived that was). Today, thanks in part to the Sanders phenomenon, millennials who were especially drawn to the Vermont senator make up the most pro-union part of the general population.

Atmospheric change of this sort was abetted by elements closer to the ground. Irate teachers in the red states were generally either not in unions at all or only in union-like institutions with little power or influence. So they had to rely on themselves to mold a fighting force, an act of social creativity which happens rarely. When it does, however, it’s both captivating and inspiring, as the West Virginia uprising clearly proved to be in a surprising number of other red states.

Class matters as does its history. West Virginia wasn’t the only place where striking or protesting teachers entered the fray well aware and proud of their state’s long history of working class resistance to the predatory behavior of employers. In the case of West Virginia, it was the coal barons. Many of the strikers had families where memories of the mine wars were still archived.

Kentucky, most memorably “bloody Harlan County,” where strikes, bombings, and other forms of civil war between mine owners and workers went on for nearly a decade in the 1930s (requiring multiple interventions by state and federal troops), can say the same. Oklahoma, even when it was still a territory, had a vibrant populist movement and later a militant labor movement that included robust representation from the Industrial Workers of the World (the legendary “Wobblies”), a tradition of resistance that flared up again during the Great Depression.

Arizona was once similarly home to a militant labor tradition in its metal mining industries. Its grim history was most infamously acted out in Bisbee, Arizona, in 1917. At that time, copper miners striking against Phelps Dodge and other mining companies were rounded up by deputized vigilantes, hauled out to the New Mexican desert in fetid railroad boxcars, and left there to fend for themselves. Those mine wars against Phelps Dodge and other corporate goliaths continued well into the 1980s.

Memories like these helped stoke the will to resist and to envision a world beyond acquiescence and austerity. Under normal circumstances to be proletarian is to be without power. Before capital is an economic category, it’s a political one. If you have it, you’re obviously so much freer to do as you please; if you don’t, you’re dependent on those who do. Hiding in plain sight, however, is a contrary fact: without the collective work of those ostensibly powerless workers, nothing moves.

This is emphatically the case with skilled workers, which after all is what teachers are. Discovering this “fact” and acting on it requires a leap of moral imagination. That this happened to the beleaguered teachers of so many red states is reflected in the esprit de corps that numerous accounts of these rebellions have reported, including the likening of the strikes to an “Arab Spring for teachers.”

And keep in mind that many other parts of the modern labor force suffer from precarious conditions not so dissimilar from those of the public school teachers, including highly skilled “professionals” like computer techies, college teachers, journalists, and even growing numbers of engineers. So the recent strikes may portend similar recognitions of latent power in equally improbable zones where professionals are undergoing a process of proletarianization.

An imaginative leap of the sort those teachers have taken bears other fruit that nourishes victory. Instead of depicting their struggles as confined to their own “profession,” for instance, the teachers today are fashioning their movement to echo broader desires. In Oklahoma and West Virginia, for example, they have insisted on improvements not just in their own working lives, but in those of all school staff members. Oklahoma teachers refused to go back to school even after the legislature granted them a raise, insisting that the state adequately fund the education system as well. And everywhere these insurgencies have deliberately made common cause with the whole community that uses the schools — parents and students alike — while repeatedly expressing the desire that children not be sacrificed on the altar of austerity.

Nothing could be more at odds with the emotional logic of austerity and acquiescence, with a society that has learned to salute “winners” and give the back of the hand to “losers,” than the widening social sympathy that has been sweeping through the schoolhouses of red state America.

Class dismissed? It doesn’t look like it.

Shares