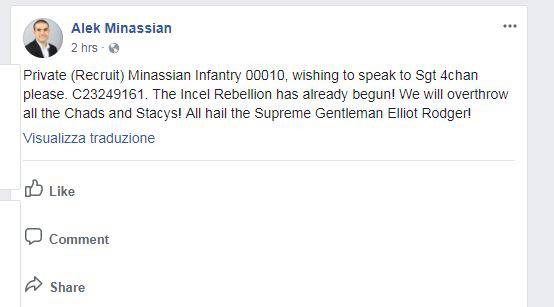

Another day, another spate of violence at the hands of a misogynist. Multiple news outlets and journalists confirmed on Tuesday that Alek Minassian, the 25-year-old man accused of killing 10 people with his van in Toronto on Monday afternoon, had written a Facebook post linking him to an insular online community of misogynists who identify as “incels,” short for “involuntary celibates.” This was reportedly the only post on Minassian’s Facebook page, posted shortly before the attack. (It has since been deleted.)

If this massacre was inspired by Minassian’s misogyny, as the post suggests, then his alleged crime needs to be firmly defined as a terrorist attack. Moreover, it is only the latest in a series of terrorist acts committed by misogynistic men whose violence must be understood as political, and linked to right-wing ideologies that deny the full rights and humanity of women.

The FBI definition of terrorism is “the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.” Misogynist violence is rarely talked about as terrorism, despite being rooted in a gender ideology and directed toward a clear “political or social objective,” the suppression or subjection of women. It’s time that changed.

Perhaps the best source of information on the internet about the incel community is a blog run by journalist David Futrelle called We Hunted the Mammoth, where Futrelle catalogs and reports on the variegated world of online misogyny. Incels are a small spin-off group from the “pick-up artist” community, which Futrelle defines as men “obsessed with mastering what they see as the ultimate set of techniques and attitudes — known as ‘Game’ — that will enable them to quickly seduce almost any woman they want.”

Incels are men who researched pick-up artistry and found that the techniques did not work as advertised. So they have become embittered and have organized a deeply misogynistic and strange online community who believe, as Futrelle explains, “that women who turn down incel men for dates or sex are somehow oppressing them.”

Incels differentiate themselves from “Chads and Stacys,” their contemptuous term for men and women who have heterosexual sex on a regular basis.

If the Facebook information is correct, as now seems almost certain, then this is the second mass murder committed by someone inspired by the incel community. The first, of course, was the spate of killings committed by a young man named Elliot Rodger near the University of California, Santa Barbara, campus in 2014.

Rodger had been a regular commenter on incel forums and explicitly imagined his massacre as an act of revenge. “I’ve been forced to endure a life of loneliness, rejection, and unfulfilled desires. All because girls have never been attracted to me,” he wrote in his so-called manifesto. Instead of responding to the murders with shame and regret, posters at incel communities have only grown more virulent and often speak of Rodger as a “saint” in their supposed movement.

Futrelle has long warned that “there will be more incel killings” because the community “appeals to young men consumed by bitterness who don’t think they have much to lose.” But incels are just one facet of a larger problem.

In 2009, George Sodini shot up an aerobics class outside Pittsburgh, killing three women in an apparent act of revenge against women in general. In the same year, Scott Roeder murdered abortion provider Dr. George Tiller, who was outspoken about his “trust women” philosophy. In 2015, a far-right ideologue named John Russell Houser murdered people watching the Amy Schumer movie “Trainwreck,” which many interpreted as an attack on the film’s perceived feminist agenda Also in 2015, Robert Dear killed three people at a Planned Parenthood clinic, apparently based on rumors that the organization sold fetal tissue for profit.

Even when misogyny isn’t the direct cause of mass-violence incidents, it’s often a causal or contributing factor. Virginia Tech shooter Seung-Hui Cho had been in trouble for stalking women in the past. Sandy Hook shooter Adam Lanza had kept a diary arguing that “females are inherently selfish.”

Then there are the domestic violence killings. Devin Patrick Kelley, who murdered 26 people in a church in Texas last year, is the most famous example of a man turning domestic violence into a full-scale massacre. But more than half of all mass shootings recorded by Everytown for Gun Safety have involved domestic violence. Indeed, Kelley’s killing spree last November came only a couple of months after a similar Texas episode, when Spencer Hight murdered eight people at a party hosted by his ex-wife.

If terrorism is violence used to force one’s political views on people, then it’s reasonable to ask why we don’t consider gendered violence a form of terrorism.

Part of the problem, no doubt, is that it’s so common for men to hurt and kill women to control them or punish them. Nearly three women in America are murdered by partners or former partners every day. Domestic violence has affected one in three women, and one in seven report having been stalked. One out of six women report experiencing rape or attempted rape. We think of “hate crimes” or “terrorism” as spectacular and rare events, not things that happen all the time.

Another aspect of the problem is that violence against women is generally understood as personal, not political. We think of the wife-beater or the rapist as a man who let his passions get the better of him, not a man motivated by an ideological view of a woman’s place and a willingness to use violence to enforce that view.

But as feminists have long argued, the personal is political. The violence and oppression women often feel in the home is related to larger political trends and ideological conflicts about gender.

Elliot Rodger openly argued that he was being deprived the sexual attention that was his due, and went on a killing spree to get revenge. What he shared with garden-variety rapists and domestic abusers wife was a sense that he was entitled to women’s bodies and attention, and a willingness to use violence to punish those, both women and men, who resisted this belief.

Gendered violence is a form of terrorism, and a highly effective one at that. Many women find their freedom circumscribed, their ambitions curtailed or their lives ended at the hands of a man who sees them as inferior by virtue of their sex. Painful as it is, we must consider the links between hair-raising acts of public violence, like this week’s Toronto killings, and the quieter forms of terrorism women all too often experience in private life. There is no way to end this epidemic of violence against women until we do.