If you could invest in superheroes the way you can invest in stocks or commodities, 1998 would have been the time to buy. Back then, superhero movies — the entire genre — seemed left for dead. Marvel Entertainment was a shell of its former self; having emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy, the cash-desperate comic-book publisher offered to sell most of its character roster to Sony for $25 million. As the Wall Street Journal reports, Sony thumbed its corporate nose at the chance to buy the full complement. It only wanted one property: Spider-Man.

Whoever at Sony turned down the chance to buy most of Marvel’s superhero movie rights at a bargain-basement price is probably still losing sleep over it. Over the past two decades, studios have fallen all over themselves to acquire superhero properties, which are now worth hundreds of millions. Disney spent $4 billion to acquire Marvel in 2009, though due to complicated contracts, movie rights for certain superheroes remained in the hands of Fox (X-Men, Fantastic Four) and Sony (Spider-Man and his universe). Recently, Disney bought most of 21st Century Fox for a cool $52.4 billion, bringing nearly all the Marvel superheroes under the Mouse’s thumb. Sony continues to milk its Spider-Man properties for all they are worth; in addition to an upcoming movie based around the supervillain Venom, the studio reportedly considered making a whole film about Spider-Man’s aunt, who has no superpowers whatsoever. (Not that that should be perceived as a slight against Aunt May; it merely shows the mundane depths of the corporate imagination.)

Something strange has happened since Marvel’s 1998 nadir. Superhero movies didn’t just increase in popularity; they did so in a specific way that is intimately tied to our political situation. Moreover, everyone in the past 20 years who predicted that pop culture had finally hit “peak superhero” turned out to be wrong. Indeed, it’s not just that superhero movies are popular; they are actually accelerating in popularity. To analogize to finance, superhero stocks are experiencing a long bull market.

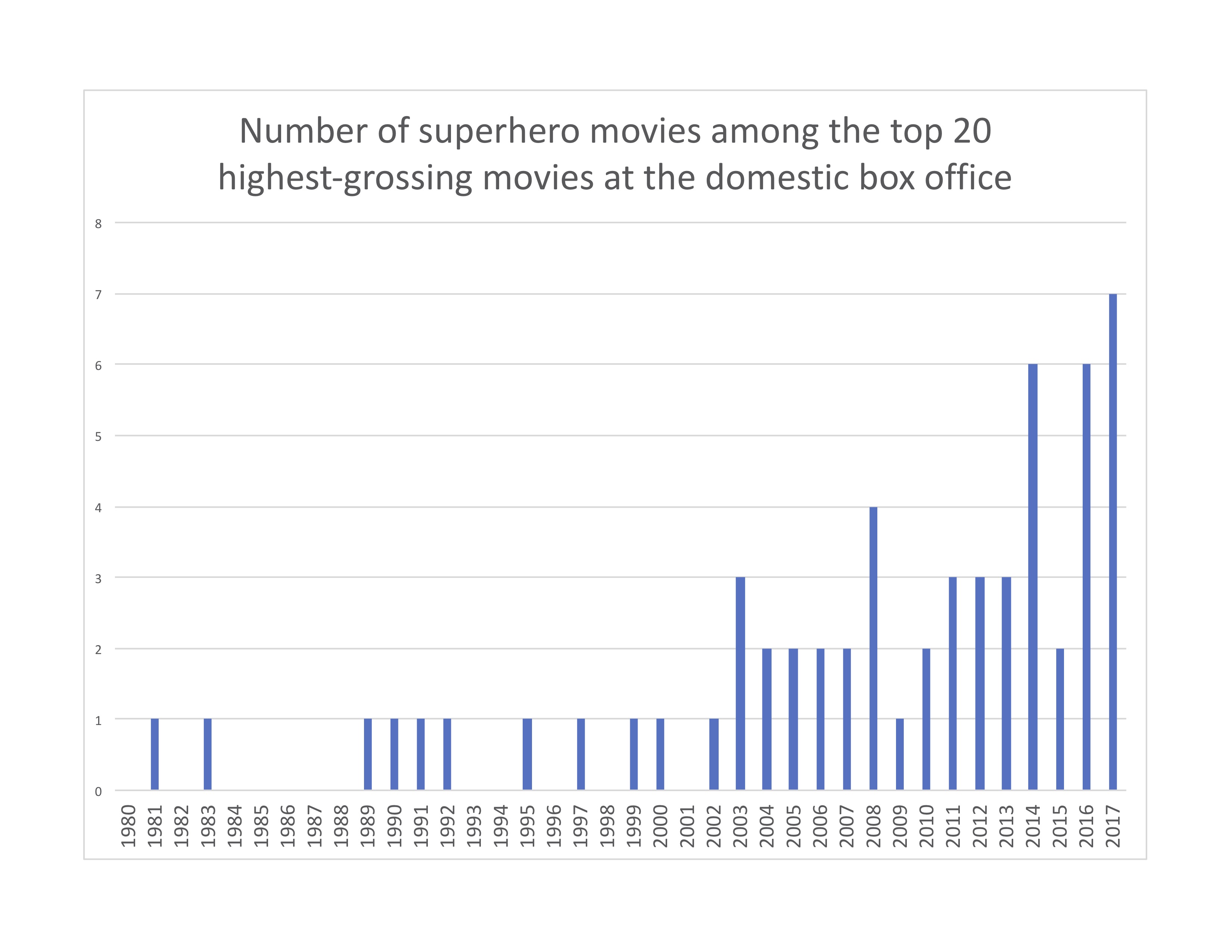

Consider the evidence: In 2017, seven of the 20 highest-grossing domestic films were superhero movies. As of this week in April, 26 percent of all domestic box office revenue thus far in 2018 had gone to a single superhero movie, “Black Panther.” This inequality in box office receipts is astounding: There have been 735 movies released in 2018 so far, and slightly more than one-fourth of all the box-office receipts went to a single one.

It’s a new-ish trend: go back in time more than a decade or two, and the popularity quickly diminishes. I built a chart, going back to 1980, counting how many superhero movies ranked in each year’s top 20 for box office revenue. Note the remarkable arc upward:

Chart shows the number of superhero films each year that ranked among the top 20 highest grossing films in the domestic box office. “Superhero” is interpreted liberally, and includes a few films, like “The Matrix” trilogy, that featured many of the tropes of the genre (flying superhumans with special powers!) and other movies that were clearly superhero movies yet which lacked the history of comic book serials (e.g., “Megamind” and “The Incredibles”). Note that the exponential-seeming arc would look even more dramatic without “The Matrix” trilogy (released 1999, 2003 and 2003) included. Data via BoxOfficeMojo.]

I don’t think the trend toward superhero movies — or the acceleration of their production — is mere coincidence. It is not simply that superhero movies are growing ever more popular; it is that their content and their themes are the ultimate reflection of this era in economic history, which we might call neoliberal capitalism.

Moreover, I would argue that superhero movies, and their increasingly expensive productions and complicated universes, are more than just reflective of our world: They are necessary to the perpetuation of neoliberal capitalism. Though the studios that pump them out almost certainly don’t know this, these movies are the political equivalent of an immune system response to a growing populist tide. The superhero genre embeds within itself the values and beliefs that make neoliberalism function.

Governance by supermen

If you have read one too many thinkpieces on the oft-hazy term “neoliberalism,” you can skip the next three paragraphs. If not, the term neoliberalism (sometimes called late capitalism, depending on the critic) refers to the specific epoch of Western capitalism that became ascendant in the 1980s, and especially so after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Specifically, it means an economic and cultural system characterized by sweeping privatization, the financialization of the economy, the rise of technocracy over democracy, and the normalization of itself as the only possible system of organizing society.

“So pervasive has neoliberalism become that we seldom even recognise it as an ideology,” writes George Monbiot in the Guardian. “We appear to accept the proposition that this utopian, millenarian faith describes a neutral force; a kind of biological law, like Darwin’s theory of evolution.”

Thus, the social welfare state in neoliberal economies becomes increasingly privatized, while politics consigns itself to debates over identity that mirror consumption habits. Websites like BuzzFeed, stores like Whole Foods, and social media and dating sites (all of them) epitomize the neoliberal notion of a “marketplace of identity,” where the consumer views their consumption as an innate part of their identity, and eventually even starts to see themselves as a consumable brand.

“Neoliberalism construes even non-wealth generating spheres — such as learning, dating, or exercising — in market terms, submits them to market metrics, and governs them with market techniques and practices,” scholar Wendy Brown said in an interview published in Dissent. “Above all, it casts people as human capital who must constantly tend to their own present and future value.”

In neoliberal economies, this obsession with individual consumer choice dramatically weakens democracy, as the market becomes the “real” place where politics are litigated — people vote with their dollar rather than with ballots. (You can see one glaring flaw already: If dollars are votes, it means those with more dollars have more say.) Moreover, individual consumers learn to obsess over their purchases and said purchases’ implications: Buying this product makes me more “green,” this product more of a “conservative,” etc. In the 2010s, these culture wars play out constantly in the internet-mediated media sphere, where every corporate decision, public figure or new product is immediately consigned to one “side” of an imagined debate. Neoliberalism “holds that the social good will be maximized by maximizing the reach and frequency of market transactions, and it seeks to bring all human action into the domain of the market,” writes David Harvey in his seminal book “A Brief History of Neoliberalism.”

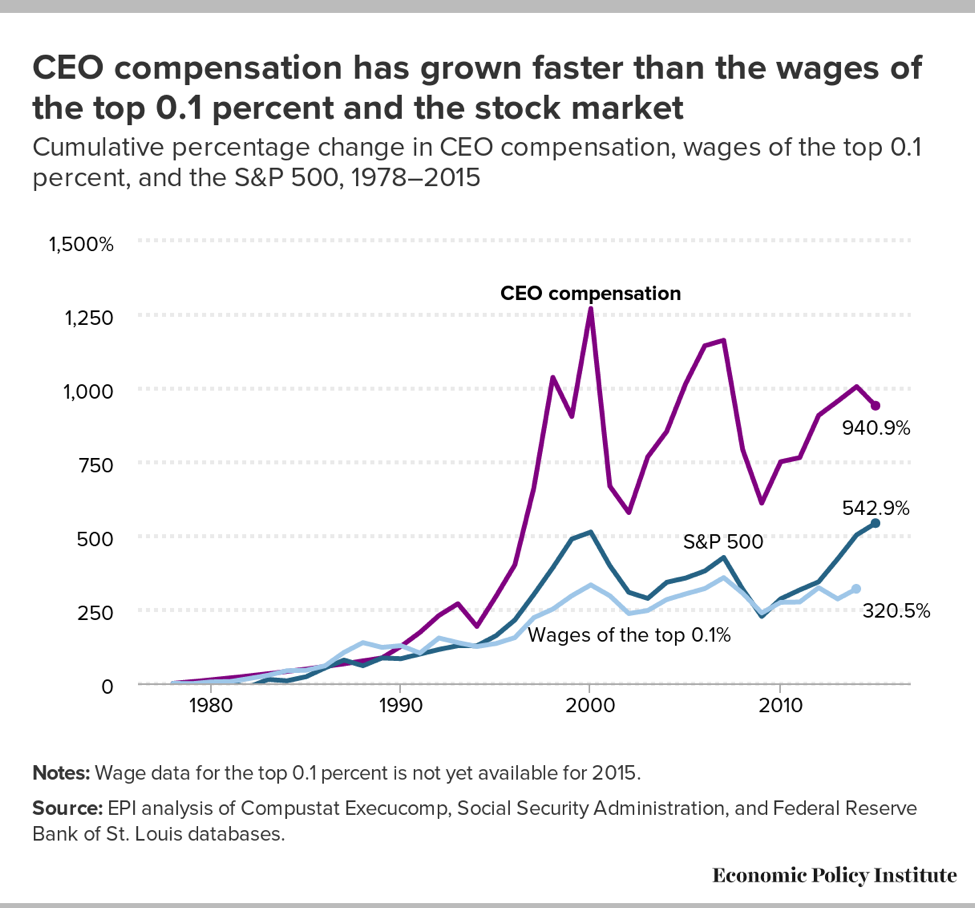

The doctrine of individualism played itself out in an attack on labor unions and a concomitant shrinking of the middle class. Historically, the percentage of unionized workers is directly correlated with income distribution. Hence, you can see through charts and graphs how neoliberalism has changed the economy. For instance, observe the evolution of CEO pay through the neoliberal epoch:

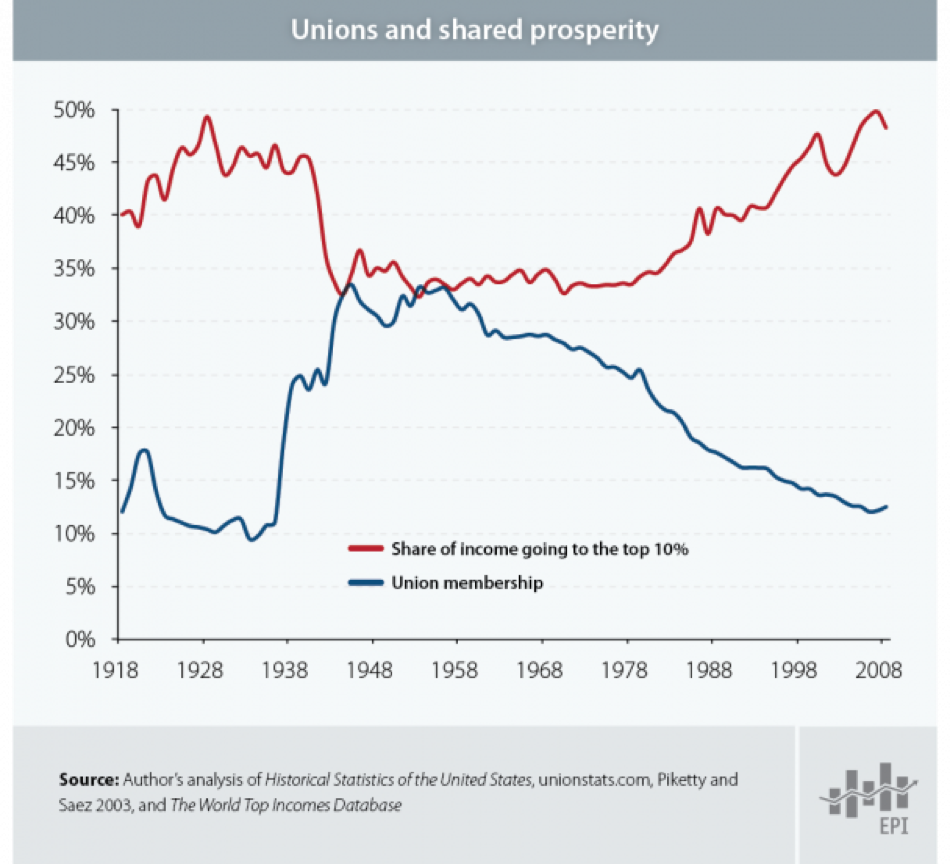

Or, consider income inequality and its relationship to union representation. Note the corresponding increase in income inequality that accelerated with the dawn of neoliberal economics:

The charts have intriguing parallels to the graph of high-gross superhero movie volume.

In any case, the result of the inherent income inequality that stems from neoliberal economic policies is that private actors gain more political power and are viewed almost as demigods by ordinary people. Politics are partly achieved by appealing to the largesse of the rich, the Gateses and the Musks and the Clinton Foundations of the world, rather than through voting or democratic participation.

Benjamin Kunkel, in a 2008 essay for Dissent, mused over neoliberalism’s predilection for producing dystopian narratives. “Every other month seems to bring the publication of at least one new so-called literary novel on dystopian or apocalyptic themes,” Kunkel wrote.

Likewise, as scholar Fredric Jameson wrote in the New Left Review, “someone once said that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. … We can now revise that and witness the attempt to imagine capitalism by way of imagining the end of the world.” Here I diverge from both Jameson and Kunkel. It’s not just dystopian art that neoliberalism generates; it produces its own utopian narratives too. Those find their fullest expressions in superhero movies.

You can probably already see how the tenets of neoliberalism fit perfectly into the superhero genre. First, the anti-democratic view of society: In both neoliberalism and superhero movies, politics and big political decisions happen because the elite (politicians or superpeople or supervillains) make them happen. Society is ruled over by benevolent philosopher-kings (plutocrats or superheroes or both) who watch over us and aid only when needed; much of the superhero-movie narrative is devoted to litigating the benevolent philosopher-king’s specific ideals (“with great power comes great responsibility”), and how they might work out best for the people at large.

Obversely, this is precisely how politics functions in neoliberalism: Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump were presented as branded superheroes, who believed they knew what was best for us, and sought to install their elite wonks to enact their benevolent (to them) policies. There’s a relatively two-dimensional view of the world at work: there are good and bad people; they are generally born that way and seldom change. The state in neoliberalism and superhero movies is almost entirely devoted to oppression and surveillance. If the state overreaches, heroes must fix its excesses; if it fails to protect its citizenry, heroes must make up for its shortcomings. In either case, its social welfare function is invisible: because people are innately good or evil, there are no social workers or teachers or other welfare-state employees whose duties might prevent villainy (or supervillainy) through social work. Superheroes are, by definition, more powerful and more important than the state.

More importantly, the superheroes’ work may save lives, but it never inherently changes the relationships of production: If the people are poor, they’re likely to stay poor. They don’t participate in redistributive politics except to attack the sort of universally detested social relationships about which there is broad consensus — for instance, slavery. Superheroes can’t and won’t save the middle class; many of them are rich anyway and stand to benefit from the kinds of inherent economic injustices that, say, Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn fight against.

Evidently we never tire of these movies, even as they trot out the same old tired tropes about human nature, criminality, justice and the relationship of the elites to the rest of us. Regardless of the studio or the brand in question, superhero films all follow the same arc: a lone, self-made superhero, or a hero and their band of allies, will face an evil villain. Mid-movie, they will come close to defeating the villain and fail. The look of the villain may change slightly in the process, perhaps move to an ancillary character, or the villain will be humanized in a novel way. There is a “hope is lost” moment where things look impossible for the hero: He or she is lying face-down in a trash truck (“Deadpool”) or has lost his throne (“Black Panther”) or is about to die in space (“Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2”). The villain comes back to face the hero, sometimes with an army (“Black Panther” or “Captain America: Civil War” or the new Avengers movie), but somehow the villain and the hero will face each other alone, one-on-one, in the end. It must be this way. In an era defined by individualism and our individual identities, there is no “we,” only “I,” to paraphrase Ayn Rand or Margaret Thatcher. We have to do things alone, just as we are the superheroes of our own imagined story arcs.

Likewise, within superhero movies, there are a series of right-wing, Thatcherite myths about society that flicker through the script, as predictable as the sun’s arc through the sky. There will be a scene in which one character dangles off a (sometimes metaphorical) ledge at some point, symbolizing the individual’s struggle and perseverance. The United States government will sometimes have internally complicated politics within the movie, but is always ultimately a force for good. The moral of the superhero story always fits into a weak, inherently problematic liberalism: People are capable of living together in harmony — strong and weak, rich and poor, super- and non-supermen — though the innate antagonisms between the aforementioned classes are ignored. The democratic whims of the populace are ancillary at best; the big political and social decisions in the superhero narrative are made by elites — politicians or superheroes themselves or the royalist societies from which they spring.

This is why so many superheroes spring from nobility: from “Wonder Woman” to “Superman” to “Thor” to “Black Panther,” super-ness and individualistic societies are interlinked; there will never be a superhero who originates from a robust democracy or an anarchist commune, because those societies don’t create individual hero myths. Those kinds of societies favor collectivism over individualism — and collectivism is anathema to the superhero genre.

Big, sweeping changes in the world occur because of the superheroes and supervillains’ battles; the rest of us are window dressing, doomed to die randomly at the hands of super-evil. When the non-super populace appear in superhero movies, they’re useless. In “The Avengers: Age of Ultron,” the people of the city of Sokovia would die without the heroes’ abilities to save them; ditto the fleeing Russian peasants in “Justice League”; ditto the hapless masses in “The Avengers: Infinity War,” whom we see only for maybe 30 seconds.

Darkest of all, superhero movies posit that humans need authority figures — that we cannot survive without policing. It is a troubling moral in an era in which a militarized police force routinely carries out sprees of racist violence on people of color. In “The Dark Knight Rises,” a version of Gotham City purged of police becomes a site of chaos and horror. I’m not sure why the Blue Lives Matter crowd didn’t rejoice more at that film’s script, as it reified Spencerian, 18th-century sociological beliefs, long since disproven. Without hyperbole, one can say that Christopher Nolan’s fairytale is totalitarian with a capital T, inasmuch as it hints that humans need authority to function at all, though there are plenty of societies, both Western communes and indigenous cultures, that attest to the untruth of that.

Finally and most importantly, the heroes always labor to make their gear and technology themselves, or with minimal help; a normalized trope of the superhero film is that the labor force is invisible. Superman’s ice castle, Iron Man’s suit, Wakanda’s intricate mining system, Batman’s gear and vehicles — in the real world, these things might take decades to construct, and would require the collective labor of thousands if not millions of human beings.

There is an exception to the rule of labor being invisible, and that is when the villain needs labor to produce something. Villains are allowed to use coercive labor, which the viewer may see on the screen: toiling orcs or slave armies building weaponry or Thanos’ cruel treatment of Eitri. Not so for the heroes; they pull themselves up by their bootstraps, design things themselves, or with the help of assistants who are well-treated or are themselves computers (e.g., Iron Man’s Jarvis), or in other cases are made by superpowers and/or magic (e.g., the temple in “Doctor Strange”). I would argue this is by design: The fact that heroes must work alone while villains use coerced labor is a dodge that intentionally misrepresents the nature of capitalist civilization at large, which is that there are always those who toil for the rich and those who profit from their labor. Superhero movies are obscurantist: in presenting the myth of the self-made (super)man, they conceal the hard economic facts of the labor that, in reality, such supermen would require.

Some readers may object to my painting of superhero films as universally embodying conservative ideals. After all, wasn’t “Black Panther” a paragon of diverse casting? Wasn’t “Wonder Woman” equally empowering for women? Indeed. The socioeconomic moral and the cultural politics of superhero films are like Superman and Iron Man: they exist in separate universes. In our everyday reality, progressive identity politics and authoritarian politics already exist separately; that’s how the left was able to win the culture war in the United States while losing the political war. Superhero movies may be great on identity politics — reflecting the larger culture-war arena where the progressive left continues to win — but terrible on economic ideas.

Superheroes of Silicon Valley

There’s a strange reflection between the superhero myths and the myths at work that drive Silicon Valley. Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg and other techies are depicted in mass media and pop culture in the same reverent tones normally reserved for superheroics, as though they alone toiled to produce their companies’ products. Musk doesn’t single-handedly design his Teslas, of course — huge armies of workers, who have documented the horrors of working for him, are the ones who create cars, rockets and solar panels. Like many of Silicon Valley’s übermenschen, Musk likes to present others’ ideas as his own; when he proposed his evacuated tube transit system, the so-called Hyperloop, he was hailed as a genius — even though comparable designs have been floating around for decades and a near-identical system was conceived by the RAND corporation in the 1970s. No matter: RAND didn’t have the mythic status of Musk, so no one noticed that he stole its idea.

The relationship between superheroism and Silicon Valley is more apt than you might think. Mark Zuckerberg designed a digital personal assistant to resemble the A.I. assistant in “Iron Man.” Robert Downey Jr. has said that he based his Iron Man character in the Marvel movies on Elon Musk. These men imagine themselves in the mold of superheroes, and society at large imagines them just the same — the screenwriters insert their tropes into their films. Do an internet search for “Elon Musk will save the world” if you want to rot your brain with thinkpiece after thinkpiece about his singular brilliance.

The technological triumphalism that Silicon Valley extols — believing “tech” to be synonymous with human progress, without a closer examination of what that means — is innate to all movies in the genre. Wakanda is supposed to be in Africa, but the way its people bandied about the word “tech” — as in “sharing their tech,” etc. — was pure Silicon Valley, a Western understanding of the phrase. “Tech” is what makes civilization better, whether you’re in central Africa or San Jose. As Eliran Bar-el writes in the Los Angeles Review of Books’ blog, the “real ideological message” of “Black Panther” “is the fantasy that only ‘technology will save us,’ coupling ancient wisdom of a benevolent king with communal science outreach.”

Likewise, just as tech critics suffer scorn for being luddites, neoliberalism has its own immune-system response against those foreign bodies who buck the precepts of superhero politics. I’m always amazed by the reaction and vitriol that arises, like a white blood cell attacking its host, whenever someone online is critical of superheroes both metaphorical and literal. Last year I wrote a short take arguing that superhero films are bad for democracy that was met with more vitriol than anything I had ever published; I had naively believed that the idea that cultural products have symbols and politics of their own that rub off on us was relatively uncontroversial. Liberals’ current culture war over representation in television and film is undergirded by an assumption that culture matters, that what we see on TV has an ideological and political and self-esteem effect on us. And whatever they may claim to believe, conservatives clearly feel the same way, and value seeing conservative tropes about patriotism, militarism and so forth in movies or on TV.

This is agreed upon on both sides, and it is also the fundament of much of the humanities — the idea that politics and culture are intertwined, inseparable. I thought it was pretty obvious that superhero movies’ common politics were, in a sense, undemocratic — characterized by hierarchy, nobility, a myopic view of crime and criminality, and libertarian notions of entrepreneurialism and self-realization. Saying this out loud, though, rankled the internet. The conservative vitriol was understandable, as the inconsistent philosophies of the right are not generally rooted in rhetorical logic; but many self-respecting liberals joined in to hate on a pretty self-evident hot take that an undergraduate English major could have written.

I see the same gut reaction whenever anyone online dares to criticize our modern superheroes, the tech elite. The scions of Silicon Valley are particularly tied to the superhero trope; criticizing Musk results in a reaction from neoliberalism’s autonomic nervous system, lashing out to quash its critics.

This isn’t necessarily the fault of those who are angry at critics. The trolls are as much neoliberal subjects as anyone, and they hold no fault for being raised in a society that teaches them that there is no alternative (to paraphrase Thatcher) to a sort of privatized, inherently unequal liberal faux-democracy. You have to look far outside the margins to see any alternative. Indeed, most pop culture nowadays posits that there is no alternative future: either we will meet our untimely end soon (something foreshadowed by the current glut of dystopian art), or we let a few benevolent “supermen” — be it Bill Gates or Donald Trump — lead us unilaterally to a world they control and manage.

I’d like to propose an alternative way of viewing superhero movies: They are the sustaining creation myths of neoliberalism. They celebrate and rehash the underlying tenets that keep neoliberalism’s subjects from revolting. These include the idea that technology is inherently progressive; that the elite can be trusted to regulate and rule over us; that police are ultimately good; that some people are born or created superior and that we should trust in them; that there are benevolent rich people who can undemocratically rule over us, a situation that is made OK because they donate to charity sometimes; and finally, that democracy isn’t always good, because some people are inherently criminal or evil, and thus the commoners need strong leaders to control and rule over us.

Superhero movies are like a fount, springing forth from a dying economic model ever-faster as it nears an inevitable collapse. If, as French critic Jean-François Lyotard wrote, postmodernism is defined by a lack of guiding social or biblical myths (“metanarratives,” in his pleonastic prose), then superhero movies are the closest we get; they are a full expression of the sociological myths of capitalist empires.

Neoliberalism spits out superhero movies because they epitomize the only means by which neoliberalism posits that society will progress: The good-natured elite rise up and conquer an ethereal, politically confusing evil — but on a private basis, without interference from the people. Likewise — and perhaps in an admission to those who understand that such a dictatorial utopia is a fairytale — neoliberalism simultaneously generates dystopian movies and literature, as the only other future its subjects can realistically envision. By providing these two poles and these two poles only, neoliberalism traps its subjects by repeating the myth that the future will consist of either A) more neoliberalism, managed by figurative supermen, or B) the apocalypse.

It’s a trap. Just as a child who has not tasted chocolate does not crave it, these poles limit our imagination and stifle us, preventing dissent or even a means of imagining an alternative. Stock up on kryptonite. Kill the supermen.