Every two minutes someone in the United States is sexually assaulted, and each year there are nearly 300,000 victims of sexual assault. But survivors are no longer silent, and new practices by police, prosecutors, nurses, and rape crisis professionals are resulting in more humane and compassionate treatment of victims and more aggressive pursuit and prosecution of perpetrators. My book, "Shattering Silences," is the first work to comprehensively cover these new approaches and partnerships.

Compassionate professionals in a variety of fields have been promoting rape reform for decades. They were often working on their own as individuals or groups of advocates and activists, social workers or counselors, or staff at bellwether organizations such as the rape crisis centers in Cleveland, Boston, the District of Columbia, Oakland, Pittsburgh, and San Francisco.

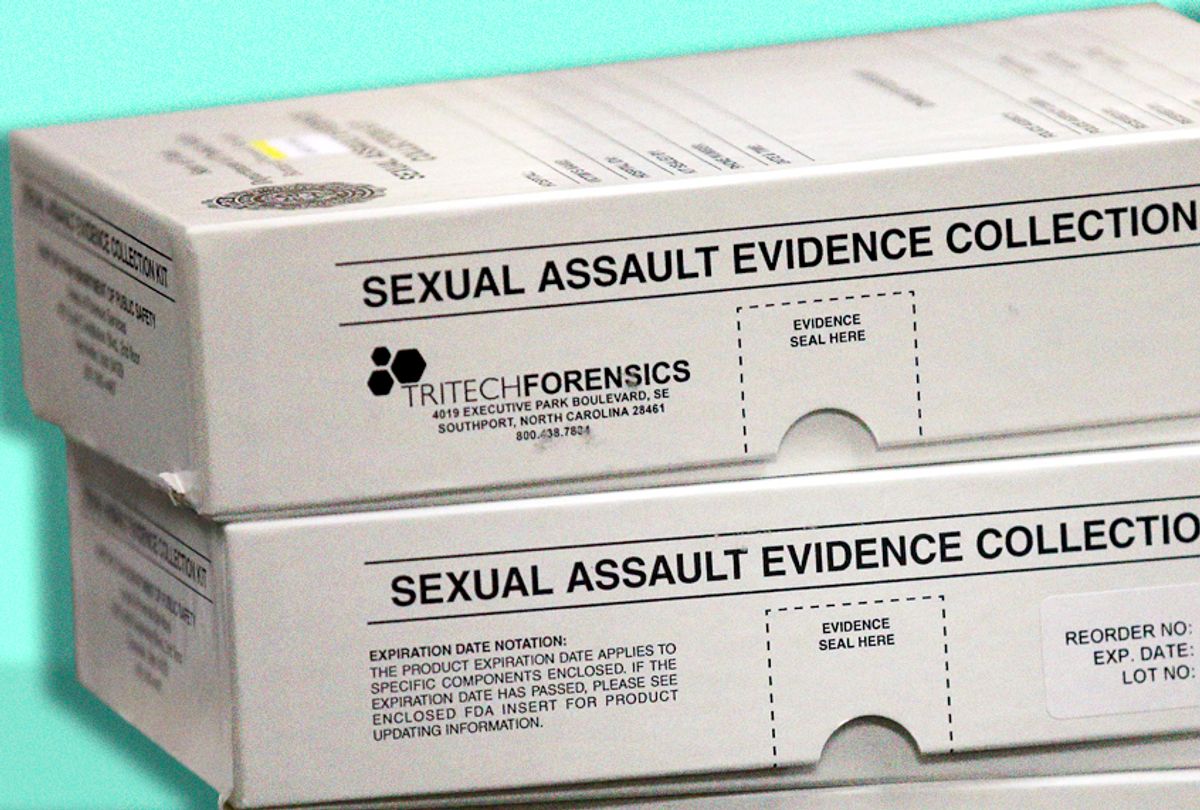

Fortunately, we are now in the midst of a growing movement that began to coalesce through a synergy of events: the advent of DNA testing in the early 1990s and the subsequent launching of the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) database in 1999 that greatly facilitated suspect identification; the revelatory research of people like Rebecca Campbell, PhD, who brought training on the neurobiology of trauma studies that lucidly explain the sometimes erratic behavior and memory of victims of rape and sexual assault in a way not previously known to many of the professionals in the field; the discovery in the first decade of the twenty-first century of backlogs of an estimated 400,000 untested sexual assault kits (SAKs) in police property rooms and warehouses throughout the United States and the ensuing decisions by an enlightened cadre of attorneys general, county prosecutors, district attorneys, and law enforcement leadership to test and investigate the cases. Much credit goes to the investigative reporters who wrote about the neglected evidence and brought it to the public’s attention.

However, the federal Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (SAKI) in 2014 represents the culmination and true turning point in the rape kit testing and processing and rape culture reform movement that’s crossing the country now. It provides financial, technical, and training support crucial to furnishing jurisdictions with the resources and knowledge to identify and disseminate best practices for this endeavor.

In fact, Kevin Strom, program director in the Research Triangle Institute’s Center for Justice, Safety, and Resilience—this nonprofit organization oversees the SAKI project—labels this era “The Golden Age of Sexual Assault Reform.”

“We’re still on the front end of this, but there is a lot of optimism that things are changing and improving,” Strom says. “We did things incorrectly for a long period of time, but there are a lot of good people out there improving the way we treat sexual assault, so it’s very inspirational.”

I first learned of these significant changes and improvements when, in November of 2009, I got involved in the case of serial rapist and murderer Anthony Sowell, who had been arrested in Cleveland on Halloween after murdering eleven women and burying them in his backyard and house. A good friend and fellow journalist, Robert Sberna, asked if I would be interested in coauthoring a book about the case. I wasn’t sure. Mainly, I wanted to see whether my hometown swept it under the rug or stepped up and said, “No more.” So, I did some preliminary interviews with people in Sowell’s neighborhood—police, urban affairs professors, and so on—and then later covered the trial with Robert. He writes a lot more about the crime beat than I do, so he went on to pen the definitive study of the case: "House of Horrors: The Shocking True Story of Anthony Sowell, the Cleveland Strangler" (The Kent State University Press, 2012).

Along the way, though, I began to meet people who were responding to this terrifying, soulless criminal by improving the way sexual violence victims and cases were handled in Cleveland. They were the solution providers to this ancient problem of cruel victim-blaming, ignoring and disregarding rape and sexual assault victims, and allowing many of the predators committing these crimes to roam freely.

Professionals such as Elizabeth Booth, RN, a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) at the MetroHealth System, or Megan O’Bryan at the Cleveland Rape Crisis Center (CRCC) or then Lieutenant Jim McPike, supervisor of the Cleveland Police Department’s Sex Crimes and Child Abuse Unit, became my initial guides into this world. Ever since then, they and many others I have met along the way have continued to help me understand the challenges their organizations were facing, the tribulations of survivors trying to recover, and the radical new approaches and initiatives that were starting to be implemented not just in Cleveland, but also in Detroit, Houston, Memphis, and now many other cities.

In 2016, I wrote a cover story for the Christian Science Monitor on what Cleveland had learned in responding to the “Cleveland Strangler” and how that had blossomed into a set of innovative and effective approaches. Just as important, the key players had all come out of their silos to work together on this insidious phenomenon, and their camaraderie was apparent at press conferences or meetings and in the friendly way they related to each other as colleagues. Because I knew it was happening elsewhere, and that Cleveland, Detroit, and Memphis have partnered their Sexual Assault Kit Task Forces (SAKTFs), I felt there was need for a compelling book that would explore the successes and challenges of this movement, as well as the professionals who were committed to doing the right thing and spreading the good word.

The history of how SAKI originated is an interesting one, with some roots in 2009. Two years prior, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ)—the research, development, and evaluation agency of the US Department of Justice—funded a study by Research Triangle Institute of why law enforcement agencies did not take sexual assault cases seriously or send evidence forward to initiate prosecution of offenders. The study found that often they didn’t understand the complex dynamics around sexual assault cases, nor did they understand the victims; law enforcement thought they were lying or partially to blame for the assault. Some didn’t fully understand the value of DNA evidence yet or believed it would cost too much to test the evidence in sexual assault kits.

That set the stage for a distinctive federal response in 2009, when Human Rights Watch published its report on the backlog of 12,669 untested SAKs found in Los Angeles that were the property of the Los Angeles Police and Sheriff ’s Departments, which shared a criminal evidence laboratory.

The report quoted Marta Miyakawa, a detective for the Los Angeles Police Department Cold Case Robbery and Homicide Division: “If people in Los Angeles hear about this rape kit backlog, and it makes them not want to work with the police in reporting their rape, then this backlog of ours would be tragic.”

The report triggered an avalanche of public, private, and journalistic responses. According to a source I spoke to who was working there at the time but who asked not to be named, NIJ reached out to the LAPD and Sheriff ’s Department and the crime lab directors they had existing relationships with to offer any help or guide them to any resources they might need to resolve the untested kits issue. The law enforcement departments were both open to disclosing what the situation was, and NIJ used it as an opportunity to research the problem in what they call a “natural experiment,” where something is already happening so they take advantage and study it. LA allowed NIJ to perform random sampling on 370 backlogged kits to see what evidence they could reap from the testing. Subsequently, NIJ published the “Sexual Assault Kit Backlog Study” in June 2012.

Concurrently, other jurisdictions started reporting enormous collections of untested kits in their property storage, and everyone began to realize it was a more widespread problem than initially thought. In 2011, NIJ decided to solicit one of their “Action-Research Projects” to get to the root of why jurisdictions were experiencing these massive numbers of untested kits. Detroit and Houston were selected as the test sites. The objective was to have researchers and practitioners in those jurisdictions work together to understand and solve the problem. If they couldn’t solve the problem with their current methods, they could make “midcourse corrections,” providing an evolutionary type of research project to uncover solutions and generate protocols for other jurisdictions to follow.

Both cities developed safe, effective means of handling victim notification. Houston devised what they called a “whole-time justice advocate,” embedding advocates in their police department to work directly with victims and investigators. Both cities began to deploy funds to hire victim advocates, investigators, and prosecutors specifically to address the backlogged rape kits. NIJ credits that project with creating the groundswell of best practices and protocols, many of which other cities, counties, states, and jurisdictions continue to implement. Additionally, according to my source, the former NIJ staff member, the number one lesson learned was the importance of having a multidisciplinary approach to take on the untested kits and resulting criminal cases.

At roughly that same time, NIJ had another opportunity to perform a “natural experiment” in post–Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, when the police there revealed—along with other serious criminal justice issues—a backlog of more than seven hundred untested kits. Mayor C. Ray Nagin, the sixtieth mayor of New Orleans, requested assistance from NIJ, which provided financial support for testing the kits and launched a pilot project known as CHOP, or CODIS Hit Outcome Project. The NIJ earned about the backlog of untested kits through involvement with DOJ working group and responded with a solution. The goal was to test a new system that notified police departments when there was a hit in the national DNA database, so that they could follow up on investigating those cases to prevent them from falling through the cracks.

In 2009, upon entering office, Vice President Joe Biden appointed the first White House Advisor on Violence Against Women, Lynn Rosenthal. (Nearly two decades earlier, Senator Biden had introduced the Violence Against Women Act in the US Congress in June 1990, and it passed in 1994.) When Rosenthal left to become Vice President of Strategic Partnerships at the National Domestic Violence Hotline, Biden replaced her with Caroline “Carrie” Bettinger-López in May 2015. Biden had also decided untested SAKs would be one of his signature issues, along with campus sexual assaults. He became the first vice president to publicly address the issue of sexual violence.

Under Biden’s leadership, Lynn Rosenthall and the Office on Violence Against Women worked closely with NIJ and other organizations such as the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and its Office for Victims of Crime to obtain a Congressional appropriation for SAKI to consolidate all the lessons learned from Los Angeles, the Detroit and Houston action research projects, New Orleans, and other research to create the Sexual Assault Kit Initiative. Angela Williamson, PhD, was named by BJA to administer the SAKI program, after she was hired in 2014 as Senior Policy Advisor (Forensics) at the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs.

In September 2014, Vice President Biden and Attorney General Loretta Lynch announced the $41 million FY2015 SAKI program. (Cy Vance, the Manhattan District Attorney, was also part of this announcement, as he released $35 million in New York City asset forfeiture funds as additional support for kit testing nationwide.) The initial awards went to twenty jurisdictions across the United States to fund kit testing, enhance investigations and prosecutions, and develop victim-centered protocols for notifying and interviewing victims.

Thus far, Congress has approved $131 million for the thirty-two jurisdictions that have now received SAKI grants, including $40 million that was expected to be disbursed in fall of 2017 that would bring the total of SAKI sites to forty. The FY2018 budget Congress is considering has not been passed as of this writing, but the proposal includes another $45 million to help eliminate rape kit backlogs nationwide. SAKI’s mission is to ensure that kits get tested and to provide the sites the resources they need to fully investigate and solve these violent crimes while always keeping victims as the focus of the cases and making sure their voices are heard and they are treated with the respect and understanding that they deserve.

SAKI grants stipulate that only 50 percent of the funding may be used for testing. The rest must be applied to investigation and tracking down offenders for prosecution. Research Triangle Institute (RTI) received $11 million to serve as the training and technical assistance (TTA) partner. They assembled a team of experts who travel to any of the sites requesting assistance or any of the District Attorney of New York (DANY)–funded sites to help them implement a tracking system, investigate a cold case, understand the victim’s response through the neurobiology of trauma research, train Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners, and so on. Key members of the TTA team include Dr. Rebecca Campbell and James Markey.

“We meet with a site and create their TTA development plan,” explains Patricia Melton, PhD, codirector of the BJA National Training and Technical Assistance Program. “We outline and identify all of their training and technical assistance needs at that time, but it’s a living document that keeps getting evaluated and modified. Then we build the subject matter expert team they need to provide their TTA, and that continues throughout the period of their grant.” The SAKI TTA website provides virtual training and support resources, too, she adds. That site is public, so the training resources are available to any law enforcement agency in the United States.

In August 2017, the NIJ published the “National Best Practices for Sexual Assault Kits: A Multidisciplinary Approach,” which includes thirty-five recommendations that provide a guide to victim-centered approaches for responding to sexual assault cases and better supporting victims throughout the criminal justice process.

In the end, there are two primary missions of this national effort to combat sexual violence. “We want to send a message to the perpetrators that they’re not going to get away with this,” Williamson informs me. “But the SAKI project also sends an even more important message to the victims that they do matter, and that’s who we’re doing this for. My hope is that it changes the way everyone addresses the crime of sexual assault.”

Strom and Melton concur. “This is just the tip of the iceberg,” Strom says of this Golden Age of Sexual Assault Reform. “We need to look back twenty years from now and say, ‘This was just the start.’”

Of course, there are numerous advocates who I haven’t examined as thoroughly, SANEs, Sexual Assault Forensic Examiners (SAFEs), police, participating prosecutors, and organizations such as Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN), the nation’s largest anti–sexual violence organization, but are doing important and far-reaching work. That was a good problem for me to have, as more and more professionals and volunteers step up to help these victims who for millennia have been left alone in their suffering and silence. There are also specific populations where the prevalence of rape and sexual assault is at such epidemic proportions that I couldn’t fairly or adequately cover them: college students, human sex trafficking victims, military personnel, and prison inmates. Perhaps in the future.

One final note on the terminology I used for people who have been raped or assaulted. At one of the breakout sessions I attended at the Sexual Assault Kit Task Force Summit in Detroit in September 2016, one of the presenters—I believe it was Kim Hurst, SAFE and director of the Wayne County SAFE program in Detroit—explained in an inside-baseball way that law enforcement agents, prosecutors, and our criminal justice system refer to these individuals as “victims”; rape crisis advocates refer to them as “survivors” or “clients,” if they have a relationship with a rape crisis center, and nurses call them “patients.”

Essentially, on the law enforcement and legal side, those professionals have to refer to them as victims, because that’s what they are in the eyes of the law. However, rape crisis advocates refer to them as survivors, whether they were assaulted two hours ago or twenty years ago. I was chided a couple times for referring to someone as a victim, even though I was talking about it in a legal context, so advocates are vehement proponents of always using the word “survivor.”

What I also found, however, is that some people in the field refer to someone as a victim if they have been assaulted recently or if they are involved in the prosecution of their assailant. Once they are on the other side of that, especially if they have made strides in taking their lives back through counseling, therapy, moving, getting a new job, exercise and fitness, etc., then they are more likely to be considered survivors.

There is no exact definition or timeline, so I have tried to use the word that best fits their status at the time I was writing about someone.

Each one of the survivors I met and spoke with, and numerous others I have read about or learned about from the professionals I interviewed—stands as a model of courage and heroism, even if they were still struggling with their recovery. Similar to veterans suffering from PTSD, whom I’ve also gotten to know in writing about Vietnam veterans or meeting veterans of the Middle East conflicts, there is no cure to the trauma they have suffered. They must find ways to recover their lives and move ahead for as long as they live. Some fare better than others.

After eight years of researching, reporting, and interviewing about rape and sexual assault, I am more convinced than ever that it is our absolute responsibility as human beings to offer any survivors the support, compassion, respect, and dignity they deserve and do everything in our power to ensure that we hold their assailants accountable and put them where they belong: prison.

Shares