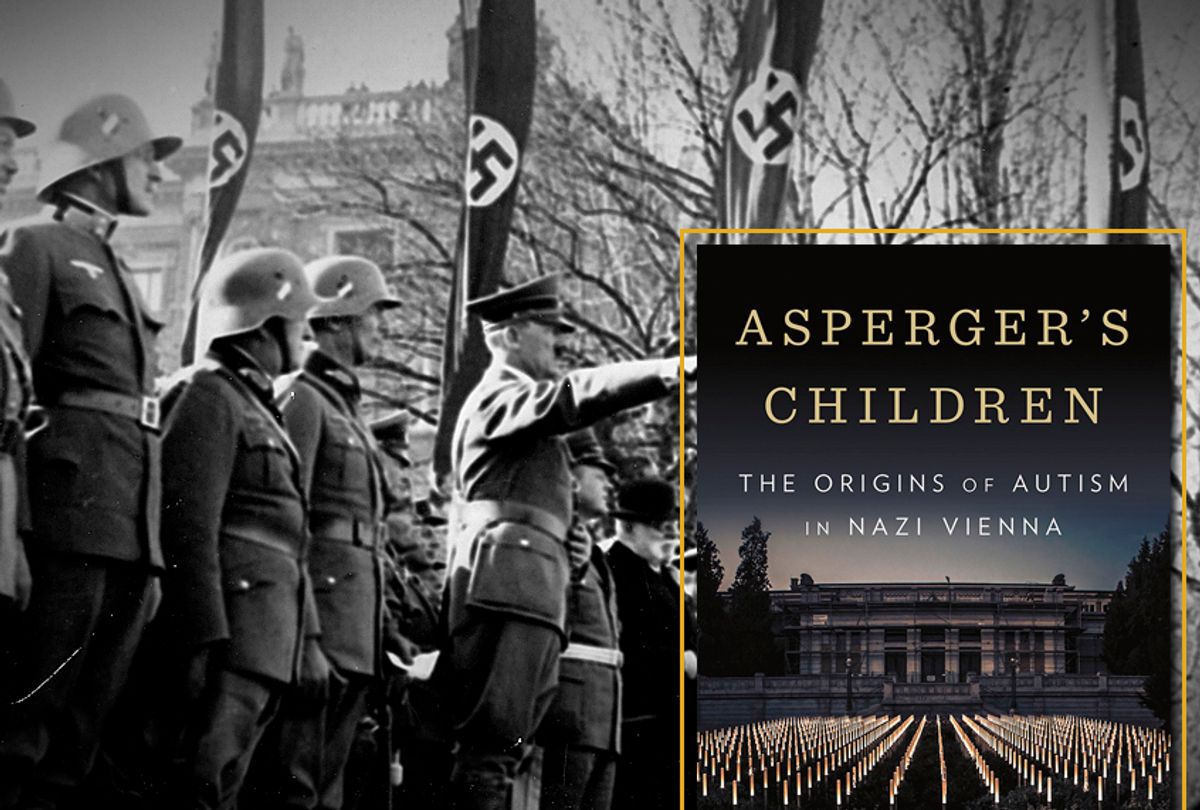

Back in 2012, the American Psychiatric Association voted to remove "Asperger's Syndrome" as an official diagnosis in their manual. Their decision was based on terminological precision rather than ethical considerations; they felt that it ought to be folded into autism spectrum disorders and argued that merging it with the broader spectrum would "help more accurately and consistently diagnose children with autism." Nevertheless, as Edith Sheffer's new book "Asperger's Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna" points out, they wound up being ahead of the curve when it came to disassociating the condition from the name of Hans Asperger himself.

As Sheffer meticulously documents and proves in her book, Asperger collaborated with Nazi Germany in unforgivable ways. He gave public credence to their most toxic views on race and biology (known as eugenics), served as a medical consultant for Adolf Hitler's administration and recommended that countless children be put to death at the Spiegelgrund, a clinic for "inferior" children. Many of Asperger's career opportunities were given to him because of the racial privileges he was afforded in Nazi Germany, and although a narrative later emerged that depicted Asperger as an opponent of Nazism, the historical evidence demonstrates that he both sympathized with aspects of and personally benefited from Nazi ideology.

"Since Asperger's work wound up broadening ideas of an autism spectrum, many laud him for recognizing and celebrating children's differences," Sheffer writes in her introduction. "Asperger is often portrayed as a champion of neurodiversity." Yet Sheffer argued that it's time "to consider what Asperger actually wrote and did in greater depth," pointing out that his story can serve as a "cautionary tale," "revealing the extent to which diagnoses can be shaped by social and political forces, how difficult those may be to perceive, and how hard they may be to combat."

This is the part where I have to temporarily remove my book critic hat and put on my personal essay hat. It isn't just that I'm on the autism spectrum myself, which I've discussed extensively in my past writing. I'm also Jewish, which means that the story of Asperger's Nazism is doubly troubling for me. On the one hand, this is the man whose early work made it possible for me and millions like me to receive something resembling a proper medical diagnosis, to say nothing of the social understanding that we often desperately lacked. At the same time, he is also responsible for the deaths of countless innocent people — and supported a regime that brutally massacred six million of my coreligionists.

How do we reconcile the man's positive legacy with his negative one?

The most obvious answer is to finish the work that the American Psychiatric Association began in 2012. Although "Asperger's Syndrome" has already been purged from the medical lexicon (albeit for unrelated reasons), it is still a popular term if for no other reason than it's convenient to use. There is an obvious difference between people on the autism spectrum who are ultimately able to function in society and those who are not. The term "high-functioning" has often been used to distinguish between the two groups, but the danger there is that it implies individuals whose autism manifests itself in more severe ways are "low-functioning" — a needless insult, and not an accurate one either.

I'm not sure which term should be used to provide the necessary linguistic clarity without becoming offensive. Very often the psychological nomenclature evolves so drastically that language which was once innocuous is now regarded as offensive or worse. As a result, I believe it is important to be cautious before branding a certain designation out of bounds.

Yet that time has come for Asperger's Syndrome. When someone refers to an individual with autism as having Asperger's Syndrome, they are paying tribute to a man whose horrific misdeeds ought to deprive him of that credit. The term quite simply has to go.

Yet how should this change the way we think of autism?

First and foremost, we need to look to Carol Povey, director of the London-based Center for Autism of the National Autistic Society. As she told The New York Times in an email earlier this month, "Obviously, no one with a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome should feel in any way tainted by this very troubling history." As someone who has grown up in a culture that often loved to deny the presence of neurological atypicality — and, for that matter, still does today — it is dangerous to simply say that Hans Asperger was a bad person and leave it at that. The legacy of Asperger the man absolutely deserves to be destroyed, but it is important to be careful.

The fact that Asperger was a Nazi doesn't mean there is anything inherently hateful or even inaccurate about the autism spectrum disorders that we learned about as a result of his work. Indeed, it's important to remember that most of what we know today about autism isn't based on his work; like so many scientists before him, he simply added a small piece to a larger mosaic in which subsequent researchers have also made their invaluable contributions.

At the same time, we must never forget that the original Hans Asperger did terrible things. It isn't simply so that his name will no longer be associated with autism. As a doctor, his foremost responsibility was to heal and improve the quality of life. Yet to quote a study by medical historian Herwig Czech:

Asperger managed to accommodate himself to the Nazi regime and was rewarded for his affirmations of loyalty with career opportunities. He joined several organizations affiliated with the NSDAP (although not the Nazi party itself), publicly legitimized race hygiene policies including forced sterilizations and, on several occasions, actively cooperated with the child ‘euthanasia’ program. The language he employed to diagnose his patients was often remarkably harsh (even in comparison with assessments written by the staff at Vienna’s notorious Spiegelgrund ‘euthanasia’ institution), belying the notion that he tried to protect the children under his care by embellishing their diagnoses.

This is not a legacy that should remain buried. It is a track record of horror that must not be forgotten. If we do, we will have lost touch with our own basic sense of decency.

Shares