It’s an old refrain uttered by police officers who realize they have shot an unarmed victim: “I thought he had a gun in his hand.”

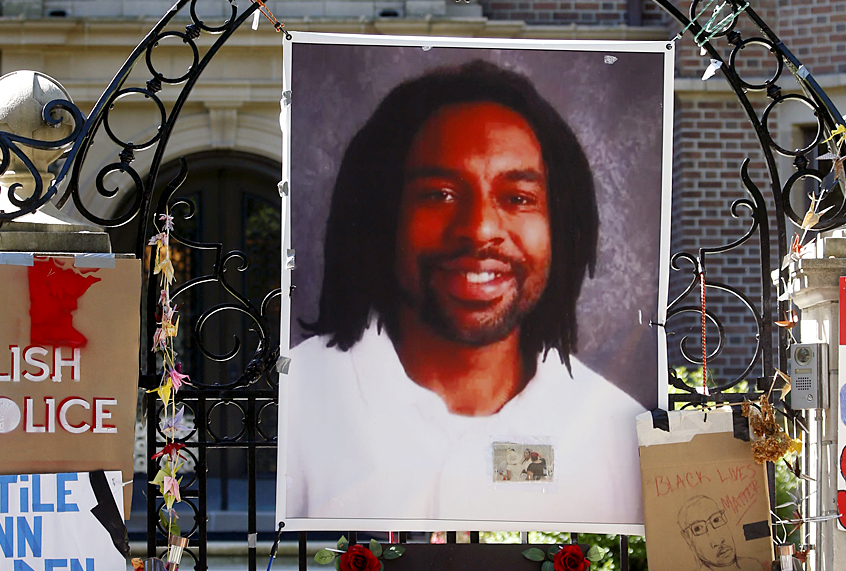

Indeed, that is what police officer Jeronimo Yanez said after fatally shooting 32-year-old Philando Castile in Minnesota in 2016. Police killings, often times driven by racial bias, have become an all-too-familiar American narrative. Indeed, a new study published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health validates what many have speculated: “Police violence disproportionately impacts young people, and the young people affected are disproportionately people of color.”

Researchers landed on the conclusion through a different approach to quantifying the tragedies of lives lost to police killings. Rather than looking merely at the stated number of deaths, they used a public health calculation that is often used to approximate the impact of a disease — thus comparing deaths of police killings to a public health crisis.

Using data collected by The Counted, a media-based source compiled by The Guardian, the authors of the report quantified the rate of years of life lost (or “YLLs,” as the study writes) as a result of police violence by race/ethnicity from 2015 to 2016. The formula required researchers to subtract the age of death from the corresponding life expectancy.

As the study acknowledges, the results are troubling and significant.

“There were 57,375 and 54,754 YLLs due to police violence in 2015 and 2016, respectively,” the report explains. “People of colour comprised 38.5% of the population, but 51.5% of YLLs. YLLs were greatest among those aged 25–34 years, and the number of YLLs at younger ages was greater among people of colour than whites.”

Comparing the results to other YLLs of different causes of death was an eye-opening endeavor.

“The burden is similar in magnitude to those due to meningitis (50,166 YLLs) and maternal deaths (56,490 YLLs), and greater than those due to cyclist road injuries (38,478) and unintentional firearm injuries (40, 752),” researchers explain.

In other words, people of color between the ages of 25–34 overall will lose more years of their lives to police killings than bicycle accidents.

“Yet many of these conditions receive more attention than police violence, in terms of grant funding, for example,” the study says.

Between 2015 and 2016, according to the data analyzed, there were 1,146 deaths due to police violence in 2015, and 1,092 in 2016. A little over 50 percent of those deaths were white people; 25.6 percent were black people; and 16.9 percent Hispanics.

The researchers hope that positioning “police violence” as a cause of death can provide “another valuable lens to motivate prevention effort.”

“Quantifying the burden of police violence is critical to mobilising adequate public health, legal and policy responses,” the researchers write. “YLLs extend the framing of police violence as a population health issue, beyond what death counts and rates provide.”

Researchers say they hope that calculating YLLs for police violence can serve as a tool for advocates, the public, political leaders and public health agencies.

While this study explicitly asks for a public health response, it is unclear if that is going to happen. From 1996 to 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were restricted from funding gun violence studies. Former President Obama ordered the CDC to re-engage with research, though it is unlikely the current presidential administration is interested.

According to a separate report by the Center for American Progress, American youth suffer the most from gun violence in America — and not only gun violence inflicted by police.

“The United States’ gun violence epidemic disproportionately ravages young people, particularly young people of color,” the Center for American Progress explains.

More civic and political leaders are speaking up about racist police violence. In March 2018, Stephon Clark was shot and killed by Sacramento police. The 22-year-old was unarmed and holding a cellphone. Civil rights activist Rev. Al Sharpton gave a eulogy at Clark’s funeral.

“No, this is not a local matter — they’ve been killing young black men all over the country,” Rev. Sharpton said. “It’s time for preachers to come out of the pulpit, it’s time for politicians to come out of the office, it’s time for us to go down and stop this madness.”