As varied and sprawling as an actor’s filmography may be, we have a tendency to link them to specific parts or types of parts. This means that regardless of how many very disparate roles Benedict Cumberbatch has played over the years, most people will see him as the modernized Sherlock Holmes or, lately Doctor Stephen Strange, aka that wizard from “Avengers: Infinity War.”

While Cumberbatch doesn’t give off the impression that he minds associations with high-concept properties, the projects he takes between them speak volumes about how he wants to be viewed in the long term — as a dramatic virtuoso, not merely a star.

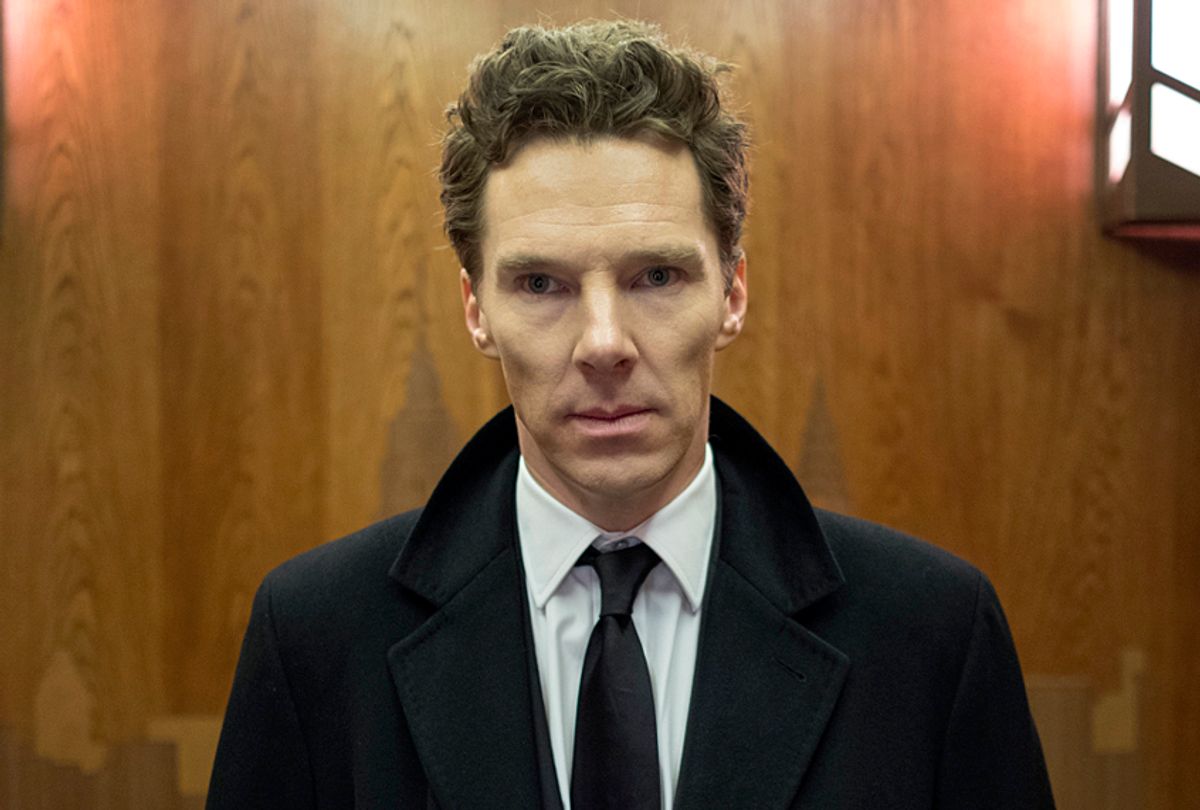

In Showtime’s “Patrick Melrose,” a five-part miniseries airing Saturdays at 9 p.m., he gets right to making his case for the former designation even as he displays an awareness of celebrity’s value. This is evidenced in his chosen entry into Edward St. Aubyn’s stories: “Bad News,” the second of St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels and the series’ first installment.

Saturday’s opening hour shows the twenty-something son of an aristocrat holing up in Manhattan’s Drake Hotel in 1982, pummeling himself with all variety of drugs and booze: Quaaludes, Black Beauties, heroin, cocaine, whiskey, anything he can shoot up or swallow, using one intoxicant to mitigate the effects of another.

And “Bad News” is a taxing proposition for Cumberbatch, since on top of bludgeoning his mind and body into oblivion Patrick must attempt, to the best of his ability, to appear respectable at times. His monstrous father, David (Hugo Weaving), has died, bringing an assortment of family friends out of the woodwork, most of them terrible excuses for human beings themselves.

Far worse are the loud, angry, cruel voices bouncing around inside his skull, all of which Cumberbatch acts out or reacts to, much to the disturbance, fright and confusion of the people around him. When he can hold himself together he mutes them with a mordant, unforgiving wit. When he can’t — when the pharmaceuticals kick in, he slurs and shivers, he screams and sweats. In the midst of an awkward conversation with a family friend he excuses himself to smear his incapacitated body down a hallway in a pathetic attempt to escape.

Much of the episode amounts to a solo piece for Cumberbatch, obscenely comical at times, pathetic and heartbreaking, awards-season bait of the highest degree. This is a compliment. Not pandering, just fact: Cumberbatch truly is that extraordinary in these episodes.

The actor calls Patrick one of two roles on his “acting bucket list.” The other is Hamlet, which he checked off in 2015 when he played the Prince of Denmark at the Barbican in London. “Patrick Melrose” calls upon different muscles than the Bard’s famous tragic figure, as Patrick is an entirely different creature of sorrow.

“Patrick Melrose,” which Cumberbatch executive-produces in addition to top-lining the cast, could have been an entirely forgettable enterprise, another entry in the poor rich kid entertainment pantheon that plays to decreasing amounts of sympathy as time goes by.

Instead, it succeeds because of St. Aubyn’s lacerating, unmerciful and highly descriptive prose, all of which Benedict takes into his flesh, and because St. Aubyn has very little to offer in the way of sympathy or credit to the upper class from whence he comes. Like Patrick, St. Aubyn’s father came from English nobility but has only a title and a perverse relationship with masculinity and worth to show for it.

He knows this world well enough to lacerate its weak spots, where the rot has compromised the structure; the apex example is Princess Margaret (Harriet Walter) depicted as an unpleasant, unhappy crone hating life even as champagne and fireworks sparkle all around her. Walter’s role is a minor one, but it says it all.

Through Patrick, it’s plain to see St. Aubyn resents what’s been done to him even as he celebrates the resilience it’s created within. As far as that goes — that is, as a tale of lasting damage — “Patrick Melrose” bears a touch of resemblance to other tragedies. Insofar as it offers the opportunity to unblinkingly observe a man’s life from childhood through his 40s, from the onset of repeated traumas that, as a friend aptly puts it “split the world in half,” through his debased junky phase and onward through sobriety, recovery and setbacks, it’s a marvel.

To be honest, it’s also not the easiest viewing experience, especially if you lack awareness of the depths to which Cumberbatch and St. Aubyn push Patrick. Watching Cumberbatch race through so many character shades proves dizzying in that first hour. But in return, subsequent episodes allow the viewer to appreciate his periods of steadiness and calm, some of it obviously painful to Patrick even though he knows the alternative, though intoxicating to remember, would end in death.

Weaving dominates the second episode, “Never Mind,” which rewinds to 1967, when 9-year-old Patrick (played by Sebastian Maltz) is summering with his family in France. It is there where he suffers the full force of his father’s brutality, mostly implied instead of shown. Weaving’s ability to weaponize fear through the faintest smile comes through again and again, along with Jennifer Jason Leigh’s realization of the sublimated torment Patrick’s mother Eleanor endures.

David is enabled by a gallery of ghastly souls, few as caustic as the social chameleon Nicholas Pratt (Pip Torrens) or as discontented as Bridget Watson-Scott (Holliday Grainger at her minxy finest when we first meet her). But even a few of these accessories receive a measure of benediction in David Nicholls’ screenplay, particularly Indira Varma’s Anne Moore, an American ridiculed for displaying a mote of care for him.

Nicholls makes optimal use of St. Aubyn’s silvery language throughout the script. But Edward Berger’s direction and James Friend’s cinematography ensure the visual experience speaks as loudly and purposefully as the people in Patrick’s world.

When his life is submerged in intoxication, real or allegorical (wealth and status are dangerous drugs in themselves here), the colors are brighter and the world is a glory. Even dim hallways glow with the loveliest blue. Sobriety, meanwhile, appears fuzzier and drained of color, telegraphing the sentiment that ugliness is part of the price of living in a state of clarity and truth.

Nestled within all of its grimness lurk touches of grace, some more obvious than others. “Everything’s a miracle, man,” a man observes to Patrick at one point -- a man who, like him, should have been dead many times over. But that brief moment claims the full weight of hope, even if it’s in passing. The story earns it as surely as Cumberbatch warrants all the accolades coming his way.

What remains to be seen, beyond the question of whether he scores an Emmy nomination, is whether the actor will actually appear for the ceremony if he does. He hasn’t always attended in the past. Considering how extensively his range showed up in “Patrick Melrose,” maybe this time he actually will show up. That is, if he doesn’t deem such a self-congratulatory society demonstration to be too garish.

Shares