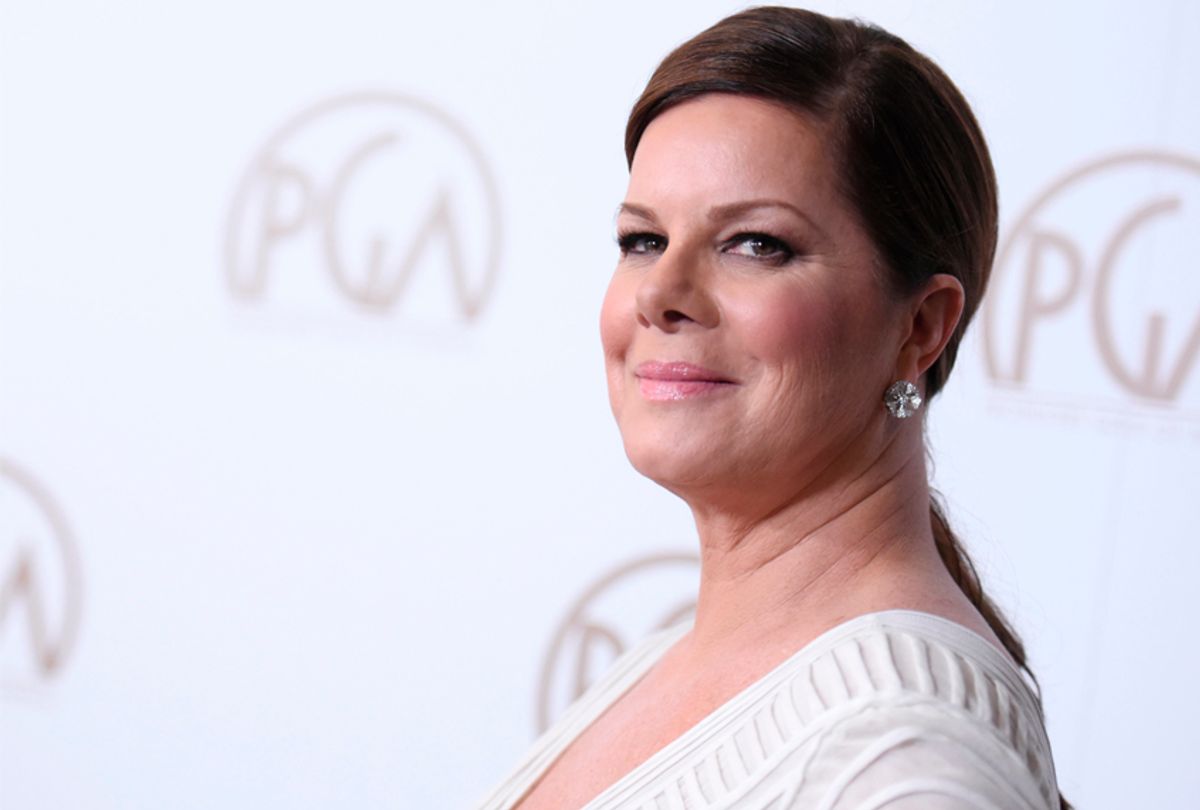

Marcia Gay Harden has captivated audiences and critics with her performances on screen and stage, notably the Ed Harris-led biopic "Pollock," for which she won an Academy Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role, and the Broadway run of Yasmina Reza's play "God of Carnage," which garnered her a 2009 Tony Award for Best Lead Actress. Currently, she stars in the CBS drama "Code Black" as Dr. Leanne Rorish, and reprises her role as Christian Grey’s mother in "Fifty Shades Freed." ("I was not in the red room of pain and pleasure," Harden told me during a recent episode of "Salon Talks.")

Now the acclaimed actress has added "author" to her credits. Her new book “The Seasons of My Mother: A Memoir of Love, Family, and Flowers” explores her mother’s life through Ikebana, the art of Japanese flower arranging, as well as her journey to support her mom’s increasingly devastating fight against Alzheimer’s.

We welcomed Harden to Salon's studio earlier this week for an interview, where we talked about Alzheimer's, aging and her mother's love of flowers. This interview has been condensed for length.

Your new book shares the story of your own life intertwined with that of your mom Beverly as she begins to struggle with Alzheimer’s. What made you decide to write your own stories so tied to hers?

Well, I think I was pissed off. That’s what made me start to write it. I hadn’t imagined me writing a memoir about myself. I thought maybe someday in the far future: “Ooh, I can’t remember when Clint Eastwood cast me.” Mom and I were going to write a flower book. She’s an Ikebana flower arranger, which is the Japanese art of flower arranging, and so we had long planned to write this flower book, [like] in January you use white chrysanthemums for a new beginning, and then I would have a little memory blurb: I remember in January mother would use white chrysanthemums like the snow or something, and then there’d be the how-to, and then you turn the page to February. Red roses for Valentine’s Day and a memory for February. And as her memory began to disintegrate, that book went on the shelf.

And I would go down and visit her and it just pissed me off. There’s nothing good about Alzheimer’s. It just sucks. It’s not the disease that you can say let’s make lemonade from lemons [about]. There’s no bright side. And so I just felt I do not want her legacy to be Alzheimer’s. I want her legacy to be the beauty of the life that she lived. And so I started writing [this book] — basically in 20-minute stretches, that was all I could do with kids in the beginning — and then I just wrote and wrote and it became this memoir with a goal to make her legacy Ikebana. But also mom always would say, “I want to be helping people. I want to be helping people,” and so that’s the goal, to spread the word about Alzheimer’s and make a difference.

Salon Talks with Marcia Gay Harden

Watch our full conversation:

Through the telling of her story, I would imagine that you experienced a lot of emotions writing the book, because a book can be a transformative experience. And in the process, I imagine she continued to decline.

Right.

What was it like to stay on task, trying to keep your thoughts organized?

Impossible, as any mother will know what I’m talking about. Staying on task is hard.

It’s the two of our lives intertwining, so [it includes] a lot of really funny stories from the beginning with my mother in Japan. We were a military family stationed to Japan. There’s this story of where my mother shoves me at the door in my 20s to an audition that I do not want to go to because I’m sure it’s a musical and not a play and then there’s mom at the Oscars with me when we’re being chased by paparazzi, maybe, or jewel thieves, maybe. We don’t know. There’s millions of dollars of jewels in the limo.

There was a moment when I stopped writing. It was toward what was now going to be the end of the book and everything had been lighter previous to it.

And then there was a chapter that talked about my divorce, my mother’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, and some darker things, and that was the hard part. I was thinking if you want the book to be authentic, you’ve got to delve into these darker subjects, but it was hard. I just stopped writing for a while and then I picked it back up and finished.

There’s an ebb and flow in the narrative that you feel, which makes it, I think, poetic. It’s a lovely tribute to your mom.

I love elder stories and my favorites especially are octogenarians and nonagenarians, because even especially with the typical memory loss of an elder, the things that they remember, and this is probably the case for your mom, are the oldest memories. Like their childhood bedroom. They may lose a sense of space and time but those are so seminal. Did she share those with you?

Well, early on, yes. I think memories are companions, and when you get older, it’s your most important companion on some level because it validates your life. It validates who you are and who you were and so to see her lose that companion was for me maybe one of the worst moments of all, to watch her friend slip away is what it felt like.

Mom would talk a lot about her past as we were growing up and by the time we were writing the book, she shared some of it. I always wanted to talk about things like the chocolate pot. Like who has chocolate pots today? My mother had a beautiful handed-down china chocolate pot. It’s from another time.

I’m from another time, as far as my kids are concerned, right? I’m from pre-internet.

So, mom was pre- all that and still managed to raise five kids on her own with the military husband who’s away much of the time at sea -- a phenomenal woman. And so the stories about her time, like, this was the time ladies still wear pearls in the morning and in the day, and gloves. When we were little, we had little Easter bonnets and gloves, and that’s what we wore to church on Sundays. It was just a different time.

Do you remember what that moment was when your mom came home and expressed such an interest in Ikebana and how that stayed with you all these years? What did you learn from it? Because there’s a tremendous amount of Japanese references in the book.

We were stationed in Japan and my sister just reminded me that I knew mom had taken an Ikebana class over there but she said, did I not remember that the first Ikebana arrangement mom did was actually on my birthday? It wasn’t my 13th, maybe my 11th or 12th birthday. I don’t remember. But she fell in love with the artistry of it. She fell in love with the philosophy of it.

And if you imagine an asymmetrical triangle — well, I think this is how my mother explained it: Here’s the vase on the bottom and it’s a flat vase and there’s this little rock that you stick the vines in and so there’s three main lines of the arrangement. The tallest one is going to be the heaven line, called the Shin line, so she would say, “Think of an arm of a dancer coming up,” so that would be Shin line. And then the second one is called the Soe. So, think of that here, the Soe line and that’s heaven, earth, and then the last one is the man line so think of my head as man line, so they come here.

It’s this natural philosophy, it’s a philosophy of beauty, and you’re supposed to recreate the beauty in nature. And it was first started by giving flowers to monks. Monks began the tradition of the arranging. It was more than just planting flowers in a vase, it was a meditation that she would do, and it was a gift that she would bring to the house, to the family. We would come in the door as little school kids, we’d see this arrangement, we'd sort of gasp. It was so beautiful.

So much beauty in the home and so much of Eastern philosophy does take on earthly elements. Right?

Yeah.

Elements of Buddhism, elements of nature from their horoscopes to everything else in the way that they see human characteristics. Did this support your journey as your mom became progressively less compos mentis? Did you feel that some of the things that she taught you about nature and the love of this beauty, how would you feel, safe?

I don’t think I feel safe with Alzheimer’s. I wish I did but I don’t. The statistics were too devastating. It’s now like 5.7 million people in America alone, 45 million worldwide who suffer from it. It’s a disease unlike cancer. You lose your voice. With other diseases, you have your voice in the disease as you fight it. You lose your voice in it, so I don’t feel safe with it, but I would feel basking in the beauty of these things that my mother taught me as I was writing the book or I would be reflective and think, look what has always been important to you.

So for instance, I have a place in Upstate New York. It’s a lot of land and a lot of nature and a beautiful lake, and I think I’ve struggled really hard to keep that place for my kids and I’ve struggled really hard to make that place work. It’s all about nature and there’s plants where my mother said, “plant forsythia here, because as guests drive in down the driveway they’ll see the lake in the background but the forsythia will greet them like a warm wash of color.” Things like that. Nature and surrounding myself in it and having flowers in the home and having it be a part of my life, my kids' life, has always been important.

The process of living with her and loving her as she’s been ill has made you an advocate for Alzheimer's research. Is progress being made toward a cure, do you think, and what hallmarks of the progress have you seen personally, if any?

Specifically, to my mother, I haven’t seen that there’s a specific drug that has made a difference for her. But there’s so much you can look at on the internet. There’s so many shows. I watch everything I can. And I just visited the Lou Ruvo Center, which is a great Alzheimer’s research center and hospital in Las Vegas, and there’s a drug around the corner that we think is going to make a difference.

I’m just an observer but very hopeful that it will make a difference.

So there are drugs coming in and there’s a lot of research on lifestyle and it’s all the basic stuff. It’s all the stuff your mother always said [you should] pay attention to: your diet, exercise and lifestyle, de-stress. So in diet, one of the big thing is information. And they call Alzheimer’s "diabetes 3."

I’ve got teenagers so this isn’t easy. I think your kids are younger, right? Try this with teenagers: “Let’s get rid of all the sugars in the house, guys.”

I need that for me.

I know. I’m telling you. It’s a mutiny. And then exercise. Guys, you have to sweat. And I have to say that unto myself, “Marce, it’s not enough to walk pleasantly on the treadmill. You've got to actually sweat.” Those are the things that make a difference.

Absolutely. I don’t know if you found this with your mother, but one of the things that I found working with elders are the small touchpoints of memory. Have you found that it’s helpful that when she isn’t aware of something, you can bring her back using any tools?

Well, that’s a really good point. And God bless the caregivers, right? They are just out there every day and there’s so many of them doing really, really important work.

What you’re talking about is improvisational, so they have training sessions where they teach the caregiver.

If an Alzheimer’s patient says, “Oh, I need to go and meet my husband,” but the husband died years ago, going, “No, no. Remember he’s dead,” there’s no gain in that. There’s absolutely no gain. To say something [instead] like, “Oh, that’s wonderful. He loved you so much.” So you join the moment therein.

You don’t necessarily have to lie or whatever, but you can always say something about that moment and that’s the moment that counts for them. They can’t remember the past. They can’t imagine the future, so being in the moment with them and finding love and care and comfort is really wonderful.

Music is another thing that people talk about a lot in terms of being able to touch people and I think that’s true. They can remember . . . I guess music must be stored in the brain in a different way. It’s really interesting. Music is often a touchstone for them. Pictures can be and sometimes are not. They don’t look and go, “Oh, yes, I remember when . . . ” because first of all, pictures look so different than they remember but it’s something about the visual they may not get. But you can certainly say their parents' names. Let’s say the mother’s name was Rose, her mother’s name was Coco. I can say, “Oh, Coco would have loved that.” That would bring my mother to a place of remembering cognition on some level.

In this context it seems dreadfully insensitive — and it’s not meant that way at all. But my friends and I, we joke that all mothers — not to be sexist, maybe it's some dads too, have "CRS" and that is . . .

"Can’t Remember Shit."

The hard drive is full, you just can’t remember shit.

With my mom, I would be like, “I don’t know remember what you’re talking about, Mom.” “I don’t remember where I put the keys.” So [the memory loss] didn’t seem like anything, it didn’t seem like impending doom. And it wasn’t until several years later that the signs were a little more obvious.

We’re not supposed to be a statistic. Mom lived the poster child life for someone who wouldn’t get Alzheimer’s, so why was she getting it? It was just really scary.

At one point [while] writing the book I thought, why do I not have more of these stories in this age of instant information? Why don’t I have more of my mother stories down, and how will my kids ever know who their grandma was if I can’t tell these stories? I didn’t want her legacy to be Alzheimer’s.

And so they’ve gotten to know her quite a bit, because I could only write by reading — because I’m an actress, so I had to say it out in a room so they would sit with me for long periods of time. “How long is this one going to be, Mom?” I’d be like, “This is a five-minute story, guys.” But they would end up learning a lot about their grandma through me.

Which is so important. And so now in a sense you’ve preserved her life for your kids. Was that a part of your reasoning?

Well, it was. Remember I started by saying I was angry. I was just angry. You expect a certain relationship but you hope for certain relationship and it was the insidiousness of the disease and you can say it’s unfair. All diseases are unfair. But it just seemed insidious to me, so writing [the book] was a way of preserving her and preserving that essence of her.

My mom is just really graceful person. She’s a really kind, graceful person and that core of her is the same. The spirit of her is the same. She’s, in a word, lovely. And even though she’s changing, physically changing and forgetting, there’s a loveliness to her demeanor that it feels so beautiful to witness. It’s still there. And I think her spirit can’t be crushed. The spirit of love cannot be extinguished.

At the very end of the book, I said, “Tell me everything you’re thinking about, Mom, everything you’re thinking about, because I’m almost done with the book and I don’t want to miss anything,” and she started talking and I could see she was . . . I said, “Tell me about love or sex or food or God or playing or Ikebana, whatever,” and she started to say something.

I said, “What do you think about?” She said, “God.”

I said, “What do you think about God?” She said, “Love.”

“What do you think about that disease?” “Well, it happens to everybody,” she said. “Fill your mind with beautiful love and thoughts and that’s what’s important. God is love and love is happening to everybody.”

Have positive energy. It was sort of like mom meets Oprah meets Deepak Chopra meets all these great spiritual teachers, and I don’t like joking about it. I hope I don’t seem jokey about it, because it’s the most serious subject in the world. But I have to repurpose what I feel into something positive, and it’s through my mother’s words that I can do that, because that’s where she is, just being in the moment with her essence and her kindness.

I did want to just to shift slightly to Hollywood before we have to wrap up, and talk about what you’re working on now. Is there a sea-change in Hollywood happening with the Time’s Up movement?

I think that the truth will be told in the amount of women’s jobs that we see the numbers rise for, although you’ve got Ava [DuVernay] right now directing, and ["A Wrinkle in Time"] was a top movie. And "Black Panther," that was a top movie, so that was a sea-change in terms of diversity and female directors.

Have roles shifted and opportunities [grown] for women over 40?

I think that roles have shifted in television for women over 40. I think in film there’s still the typical hierarchy of [casting] this many women's roles and this many men’s roles. I mean, think about any war movie, think about "Game of Thrones," think about any of these things that we watch that are . . . they’re male-heavy. Is it shifting? Well, thank God for Amy Schumer and people like that. Yes, it will.

Shares