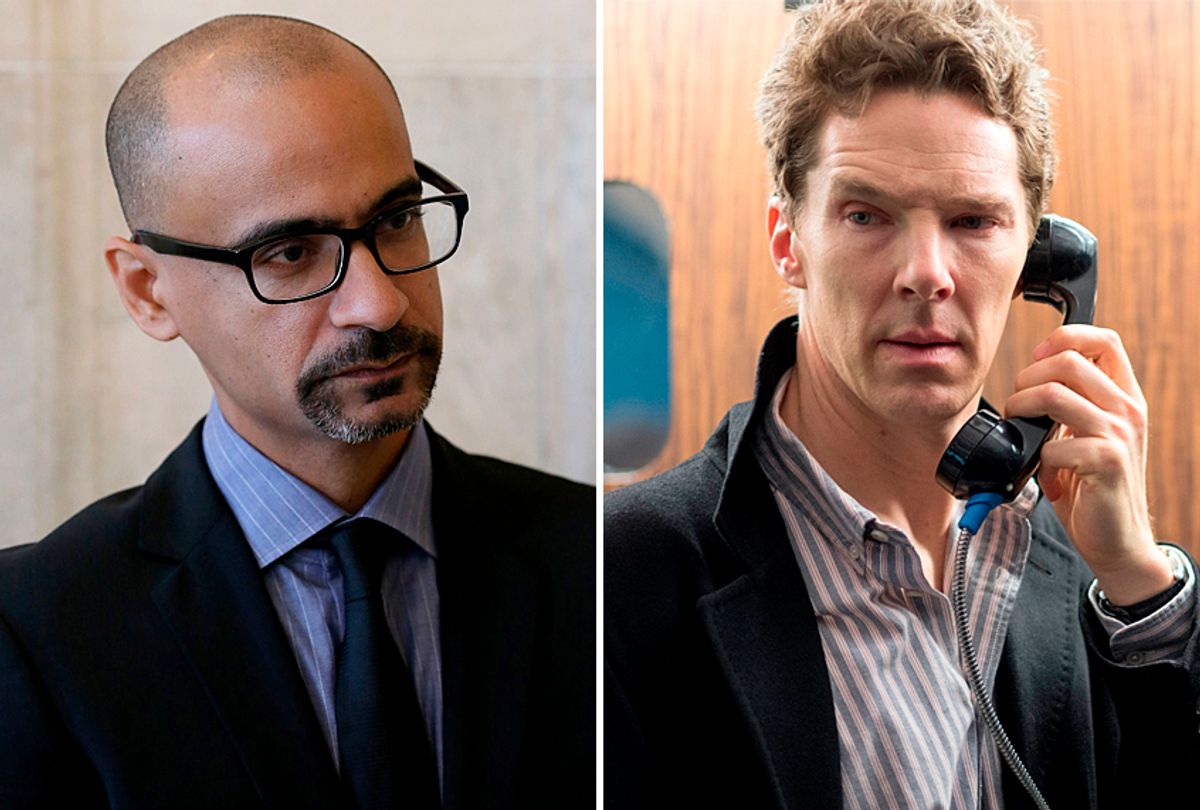

When Pulitzer Prize-winning author Junot Díaz came forward in the New Yorker last month with his shattering account of his childhood rape, he also hinted that there was more to the story. For starters, the essay was called cryptically, "The Silence: The Legacy of Childhood Trauma." But is part of that "legacy" a passed-on pattern of abuse?

The long-term consequences of abuse — in particular, sexual abuse — have been a subject of public conversation for several years now. The watershed disclosures of widespread molestation by members of the Catholic clergy that began emerging in the early 2000s revealed a population of adults who had been carrying their scars in silence. The revelations of harassment, abuse and assault across every industry that the #MeToo movement has uncovered over just the past several months have likewise brought the topic to the forefront. And along with questions of how abuse flourishes in so many different spaces, there are the questions of why it happens in the first place, including whether it's learned behavior.

In the span of a little more than a month, Junot Díaz's public identity has morphed from acclaimed author to abuse survivor to accused perpetrator of misconduct. In his April New Yorker essay, Díaz revealed that he was molested when he was eight by a trusted adult who then threatened him if he didn't return to be raped again.

He spoke of experiencing, several years later, "[c]lassic trauma psychology: approach and retreat, approach and retreat. And hurting other people in the process." He admitted to cheating on a woman he loved. And he said that now, "I’m in therapy twice a week. I don’t drink (except in Japan, where I let myself have a beer). I don’t hurt people with my lies or my choices, and wherever I can I make amends; I take responsibility. I’ve come to learn that repair is never-ceasing."

The trajectory of the narrative was clear — I experienced pain. I referenced this pain in my creative work. I also inflicted pain, to a lesser degree, in my personal life. I am now healing.

Díaz's account drew empathetic responses and praise for his candor about such a difficult subject. It also made some people wonder about the "hurt" he alluded to inflicting on others.

Then, in early May, author Zinzi Clemmons confronted Díaz during a panel at the Sydney Writers' Festival, reportedly asking about an incident six years earlier, when she was a graduate student at Columbia. She then followed up on Twitter:

As a grad student, I invited Junot Diaz to speak to a workshop on issues of representation in literature. I was an unknown wide-eyed 26 yo, and he used it as an opportunity to corner and forcibly kiss me. I'm far from the only one he's done this 2, I refuse to be silent anymore.

— zinziclemmons (@zinziclemmons) May 4, 2018

She added that "I told several people this story at the time, I have emails he sent me afterward (*barf*). This happened and I have receipts."

Author Carmen Maria Machado recounted her own experience with him, claiming he berated her at a reading for asking about his characters' attitudes toward women. She added:

In the intervening years, I've heard easily a dozen stories about fucked-up sexual misconduct on his part and felt weirdly lucky that all ("all") I got was a blast of misogynist rage and public humiliation. — Carmen Maria Machado (@carmenmmachado) May 4, 2018

In a statement to the New York Times, Díaz said, “This conversation is important and must continue. I am listening to and learning from women’s stories in this essential and overdue cultural movement. We must continue to teach all men about consent and boundaries.”

On Thursday, the Pulitzer Prize board announced it was conducting an independent review of Díaz, and that he was stepping down as the chairman — mere weeks after he'd been elected to the posting. MIT, where Díaz teaches creative writing, is also looking into the allegations. The school said this week that it "doesn't tolerate sexual harassment but that it also strives to protect the rights of both the accusers and accused."

No one would conflate the behavior Díaz is accused of with the sexual violence he's endured. But in his own essay, he drew a connective line between his childhood trauma and the "depression and uncontrollable rage" that followed soon after. Scars that manifested in drinking and taking drugs, and in sexual betrayal. And, according to the accounts of other women, aggressive and inappropriate behavior.

The latest twist in the Díaz story comes right at a moment when another, similar story is making a much anticipated debut. On Saturday, Showtime debuted "Patrick Melrose," the Benedict Cumberbatch miniseries based on the autobiographical novels of English author Edward St. Aubyn.

From an early age, St. Aubyn's father raped and emotionally terrorized his young son. The author started using heroin in his teens. By the time he was an adult, his consumption of drugs and alcohol was, to quote a 2014 New Yorker profile, "astounding." The title of that feature is "Inheritance."

The first two episodes of "Patrick Melrose" shift between the shattered childhood of the young character Patrick and the self-harming excesses of the man. It's a harrowing, often surreal journey, one that tracks sexual violence as a catalyst for future destructive behavior. Later episodes will trace Patrick's attempts at sobriety and his evolution as a husband and father. The path again is obvious and logical — the damage done comes back and manifests later. It manifests in hurting yourself and hurting others.

Because of the often secret nature of abuse, the statistics on its cycles and long-term ramifications are inconsistent. But according to one report in Advances in Clinical Child Psychology, "40-80% of juvenile sex offenders have themselves been victims of sexual abuse." A 2013 Guardian feature estimates that "[b]etween 30% and 40% of people who are abused as children go on to become abusers themselves." In a 2009 story for Psychology Today, Steven Stosny, Ph.D., said that in his anecdotal experience, abusers often "describe themselves as victims."

Similarly, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs notes that "[i]n one group of self-harmers, 93% said they had been sexually abused in childhood. Some research has looked at whether certain aspects of childhood sexual abuse increase the risk that survivors will engage in self-harm as adults. The findings show that more severe, more frequent, or longer-lasting sexual abuse is linked to an increased risk of engaging in self-harm in one's adult years."

Yet the road for most survivors is not to perpetuate harmful behavior. That the pool of abusers and self-harmers contains survivors of childhood abuse does not mean that abuse survivors are therefore abusers or self-harmers themselves. As the UK organization Rape Crisis reminds, "The vast majority of those who are sexually abused as children will never perpetrate sexual violence against others. There is no excuse or explanation for sexual violence against children or adults." And a 2015 study released in Science magazine posited that statistics on intergenerational abuse may be biased, based on whether or not the abuse has been reported and then tracked.

Abuse has long, long arms, and there's no way that the horrors inflicted upon a child won't color his adult experiences. But that manifests in many ways. Every survivor's story is unique, and the experiences of two novelists are unique too. Some of the consequences of Junot Díaz's experiences may have extended through and from him. But it's important to remember that abuse is neither an excuse nor an inevitable sentence. And legacies and inheritances aren't always passed on.

Shares