Author Stacy Horn loves New York. Over her 20-year career, she's written about its cold case squad and its famous ghosts. Now, in her newest book, she explores one of its most notorious corners.

It sounds like a contemporary arch conservative's political platform, but it was a reality for 19th century New Yorkers. In a city of vast wealth and opulence, the most marginalized members of the community — the poor, individuals who'd committed even minor crimes, those who couldn't afford their medical bills, the mentally ill or just a little too troublesome — could be shipped off and forgotten.

Off the tiny island of Manhattan, an even tinier piece of land called Blackwell's Island was home to a lunatic asylum, workhouse, alms house, charity hospital and prison. Most of the men, women and children who wound up there endured barbaric conditions, and many never returned. The asylum gained its greatest infamy in 1887, when a 23-year-old journalist who went by the pen name of Nellie Bly published a sensational exposé of her brutal undercover experience there. Yet even a subsequent grand jury investigation did little to move the needle for the inmates there.

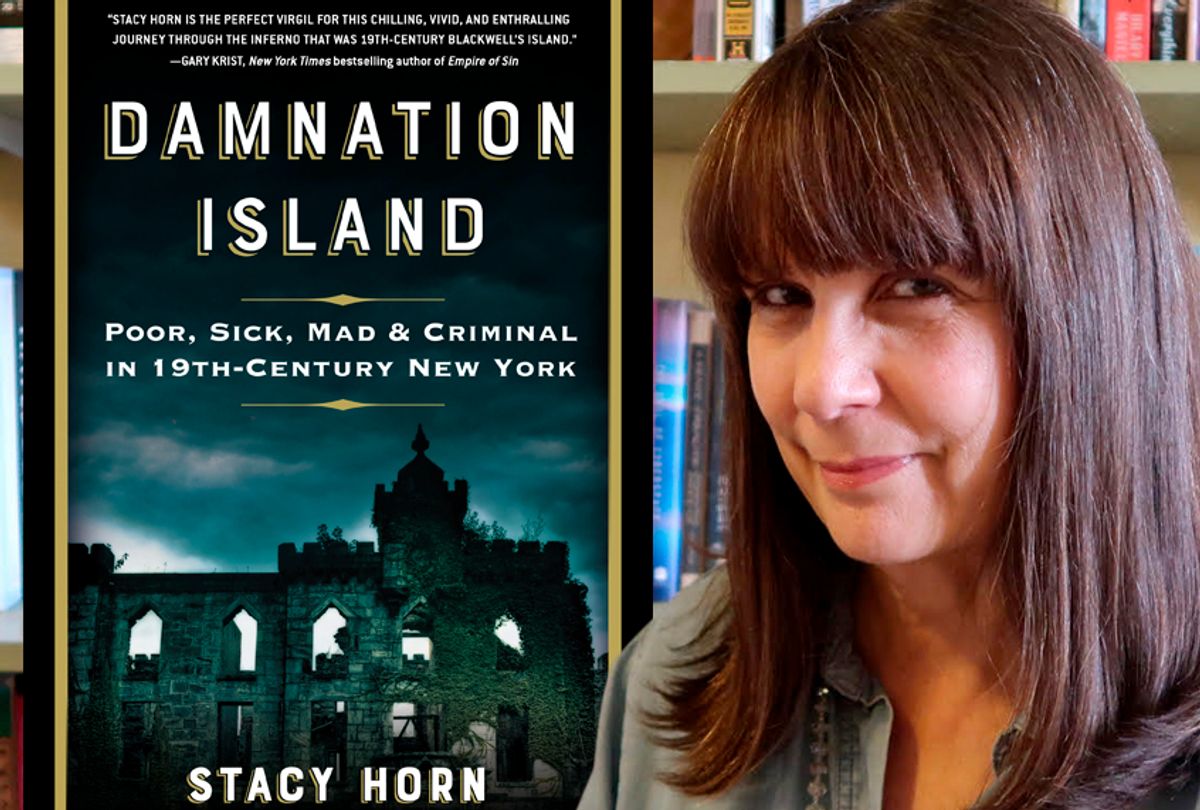

In "Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad & Criminal In 19th-Century New York," Horn delves into the Dickensian conditions that the island's population lived under, explores how Blackwell's got that way in the first place and uncovers the previously untold tales of individuals who found themselves there. It's a stunning examination of bureaucracy gone wrong, and the evolution of the place we now call Roosevelt Island. Salon spoke to Horn recently about the book — and its very modern message.

Nelllie Bly is such a hero. Reading this book and having her inserted in the middle of this story was really fascinating.

She was amazing. She gave one of the few first person accounts from the inside.

What’s surprising is that I didn’t realize how little effect her whistleblowing had.

Yes, exactly. It was sensation, but there was almost no change. They got a little bit more money the next year, but not enough to really change the lives of the women inside. But doesn’t it feel like the exact same thing now?

I was thinking her story was the equivalent of a Twitter storm, where it’s, “Let me tell you all about this thing that happened." And then two days later, basically, nobody cares anymore.

Exactly. It’s so depressing.

Early on in the book, you draw a very clearly articulated parallel between what happened at on this island and what is still happening now — the idea that people who are mentally ill are dangerous and people who are poor are lazy and bad. And in a very real, physical space way, the mentally ill and the poor just belong lumped together.

Yes, with criminals.

The criminalization of poverty and mental illness.

Exactly. I didn’t research how far back this goes, and I’m sure there was always a little bit of that going on. But once they threw them all together on one island, it just completely cemented that association in people’s minds.

The other thing is the way that mental illness was understood, and the way that that the labels of mental illness and also disorderly conduct disproportionately affected women.

Yes, and the black community.

I do want to talk about how you had to address the issue of race in the book, because it is a tricky thing. It’s not like there was no racism in New York City in the 19th century, but because of the classifications of race, it did make the island unique and it did make different populations based on race.

I did address the fact that there were so few African Americans on Blackwell's Island. I think that was because they were so mistreated in the earlier incarnations of the alms house. They pooled their money and created their own institutions, which the Department of Public Charities and Correction supported instead of housing them on Blackwell's Island.

Let's talk about how women were affected, because if you were a lady who was angry at your husband, you could be considered a crazy person. Or if you were postpartum and had depression.

Yes, things like panic attacks. How many people have had panic attacks? That could get you into the asylum.

Then it was basically like a one-way ticket.

Their time there could be a lifetime. For many, it was.

What killed me was when they had a Senate investigation in 1880. One doctor testified that when he first started working there, he started going through everyone’s background in the asylum. He found 60 women who were there without any records, so nobody knew who sent them there or why or what their issues were. And yet they just remained.

You draw that parallel too to the way that the detention system works now for so many people. So many people who get arrested and can’t post bail. The poor population is disproportionately penalized. And, of course, we also see this with immigration as well.

My book about the cold case squad and this book have just made me completely an advocate for criminal justice reform and now welfare reform and mental health, and public health issues reform. We know how there’s a big movement now to close down Rikers [Island].

They had a penitentiary and a workhouse at Bellevue, and they realized that it wasn’t working. They built these state-of-the-art facilities on Blackwell’s Asylum. Then by the end of the 19th century, they said, “OK. It’s not only not working, it’s so horribly bad that we've just got to tear this building down and start from scratch. And so they bought Rikers, and build a new penitentiary and workhouse there. They recreated same exact problems that they had on Blackwell’s Asylum.

When reformers talk about closing down Rikers Island, most of them are actually making some very, very important points so that we don’t just do the same exact thing again. It isn’t just a matter of building state-of the-art facilities. We have to reform how we send people there, so get rid of bail, reduce some prison population.

The only thing I would add — and I got this actually from the wardens of prisons, who've said this themselves — “We can’t help but notice that you never send wealthy people to us, and we know it’s not because the wealthy don’t commit crimes." I would say that whatever facilities you build, we have to investigate, arrest and prosecute white-collar crimes to the same degree that we are prosecuting crimes by the blue-collar population. I’m positive that if prisons were filled with as many businessmen and bankers, they would never become essentially the hellholes that they did.

And the fact that prison then as now is a money-making racket. But I didn’t know the history of how that system operated in New York City around the turn of the century and what was going on there.

We’ve always known. We knew right from the start it was bad.

Obviously, we have come far in terms of our understanding of mental health and we don’t call them "lunatic asylums" anymore. But what has happened instead, is now mental health issues for people who have the financial resources have become, “Yes, there’s no stigma. I’m going to talk about it. I’m going to write my book about my struggle,” and everybody rallies around that. Then what happens to poor people who are mentally ill, is that they just fall off the map completely.

Like when Trump recently called to return and bring back asylums, I screamed, because the point about this and why they are bad is that these asylums are for poor people. The wealthy people are always going to be able to take care of themselves. The only people going to asylums are going to be once again the populations that we'd really prefer to imprison. But we're going to put them in asylums instead, and treat them badly because certainly under this administration, we’re not going to give [the institutions] enough funding to treat them humanely.

Another thing that you also talk about that I really want to get into is this idea that if you’re poor, we can’t help you. Helping you will just make you weak. You described this in a book, where people would say, “Well, don’t give to the beggar women on the street with their babies, because that is just going to encourage more of the same. We don’t want to do that." Why do you think that is such a persistent trope?

Because it sounds reasonable. When I read that Josephine Shaw Lowell made that point that we should have arrested [these beggars], it sounds so cruel. But really, she was more hopeful about the system. She thought, if we arrest her, then she’s going to be diagnosed in what category she belongs, and put in the institution that would provide the care that she needs. But, of course, the system didn’t work that way, which Lowell recognized towards the end of her career.

We’re Americans, we pull ourselves up by our bootstraps. But as she points out — and I quoted her in the book — for certain people, they are kept down because they don’t have the freedom to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. They don’t have the same opportunities. They have stigma attached to them. There are so many closed doors to them.

The thing that intrigues me about this island is it was just, “Here’s your one-stop shopping experience for marginalized people on one island. New York City, we’re just going to ship everybody off to one place, out of sight, out of mind." That is still considered, in some ways in our culture, what we should just do.

People just don’t believe how bad it is, how unfair it is. Even when they see just endless, endless, endless evidence that the system is unfair. And yet it goes on.

Along with this idea that people fall on hard time through their own weaknesses and through their own fault. What this island was, was just unbelievably clear-cut manifestation of that contempt.

Yes. The people who worked there certainly didn’t think that. They might have when they started, but after working there, they were filled with compassion for the position that so many of these people were put in.

We would see it when people went to the alms house, they were literally judged. They'd mark on their files, things like "hopelessly dependent."

This went on for so long, with people coming forward and talking about it — people who had worked there, people who had been discharged. And there was this incredible indifference, just “We don’t want to hear it.”

Yes. I talked about the Senate investigation in 1889. They didn’t make a single recommendation of how we might fix this. They just published the testimony and that was that.

There was the one case that I wrote about where one inmate in the asylum was murdered by one of her roommates. The nurse had come upon them and she closed the door, basically because she was not in the position to fight down this woman who was committing the murder. She didn’t want that woman running free, murdering others in the asylum.

There were a grand jury investigation that concluded that the doctor was at fault. The woman died because they refused to admit her to the hospital, even though this nurse begged him repeatedly. They just refused. The grand jury said that the doctor was at fault, and the commission was at fault for hiring inexperienced doctors to run the asylum, and hiring convicts from the workhouse as nurses and attendants. This is what the grand jury concluded, and then the only person who got fired was that nurse — the only person who tried to save that woman.

I think, as a reader, why this book feels especially horrifying and especially heartbreaking is that it doesn’t feel like it’s a story that takes place in the past at all. You talk about Nellie Bly’s experience as being that basically, she was water-boarded.

Every time I would read arguments and justifications of why things were, it reads exactly as the things people say today.

It is also interesting to me when I go to Roosevelt Island now and see what it has become. You can go to the Octagon apartment complext, which describes itself as a historic building. The words you don’t see anywhere here are “lunatic asylum.” You don’t see that this is the place Nellie Bly exposed. You’re not going to rent apartments by saying, “This is where women were neglected and abused . . . with river views!" But it does speak to the forgetting.

In the show “The Alienist,” based on the Caleb Carr book, they have a scene that takes place in the lunatic asylum. I watched very, very carefully. It was kind of brilliant. They have a line of women sitting in chairs in restraints, not allowed to move or talk, which is pretty much how it was. I didn’t find anything that said out and out that every woman would been in restraints, but some of them would have. Some of them had no choice but to urinate in their chair because nobody would take them out to go to a bathroom. [On the show,] the scene has a woman who works for the police department walking by this line of women and one woman calls out, “Help me, help me, help me.” I’m thinking it was probably exactly like they pictured.

You let the information speak for itself when you describe the orders that were placed for these restraints and for these goods. They tell the story because we don’t have that many accounts anyway of the people who actually were inside there. And it is also the story about the abuse of children and babies, the way that children and babies fell the wayside. It reminds me so much again in this culture of alleged pro-life and pro-family. It also so much just speaks to the misogyny of it, the way that women and pregnant women were really just thrown off into the wilds.

What you have if you don’t give women the ability to have safe abortion, is you have places like Blackwell’s Island, where poor infants were sent and mortality rates reached almost 100 percent.

It is a very compassionate book and the message parallels to where we are right now are. If you tell the story and then someone can really be open to it with open ears and then open heart, how can they walk away unmoved?

I hope that is the case. That’s my goal.

Shares