It’s been three years since the public debate over the color of “the dress” split up friendships and divided families. (For the record, it was black and blue.)

This week, a similar viral debate emerged online — and this time, it’s an aural illusion rather than a visual one.

A two-syllable audio clip of a computerized voice has made waves on the internet, sparking a debate: Does this clip say “Laurel” or “Yanny?” The answer is — well, it’s whichever of the two you think you hear, though there have been some reports of people hearing “Yammy” too.

If you haven’t heard it yet, click below:

What do you hear?! Yanny or Laurel pic.twitter.com/jvHhCbMc8I

— Cloe Feldman (@CloeCouture) May 15, 2018

Celebrities and public figures have weighed in on the head-scratching debate over how two different-sounding words could be interpreted from the same audio clip.

Literally everything at my show just stopped to see if people hear Laurel or Yanny. I hear Laurel. https://t.co/efWRw1Gj0L

— The Ellen Show (@TheEllenShow) May 15, 2018

I only hear Yanni 😉 hahaha https://t.co/WrMMVvl8iX

— Yanni (@Yanni) May 15, 2018

Cloe Feldman, a social media influencer, tweeted the clip after her sister, Sage, discovered it in a Reddit thread and sent it to her. Feldman told Salon she did not know who the original poster was, but was hoping to find the person to properly attribute the viral meme to its original creator.

On Wednesday, The New York Times traced the origin of the audio — which was posted on Reddit by user RolandCamry — back to 18-year-old Roland Szabo, a high schooler in Georgia. He told The New York Times that he discovered the audio clip on the vocabulary.com page for the word “laurel.” While working on a story project, he played the clip through his computer speakers, which led the room to disagree on what the artificial recording was saying.

So why do some people hear one sound and others hear another? No one knows definitively, but scientists and audiologists are already studying and speculating on the Yanny/Laurel phenomenon.

“’I’m not sure if we will ever fully know what exactly is going on because, to be honest, we don’t fully understand how our brains understand and perceive speech,” Gretchen Perkins, an audiologist at Sound Speech and Hearing Clinic in San Francisco, told Salon.

One auditory neuroscientist, Gabriella Musacchia, has already run some brain scans to try to get to the bottom of it. Musacchia is an assistant professor in the Department of Audiology at the University of the Pacific and a research scholar in the Department of Otolaryngology at Stanford University.

When she walked into her lab today, she set out to get to bottom of this enigma.

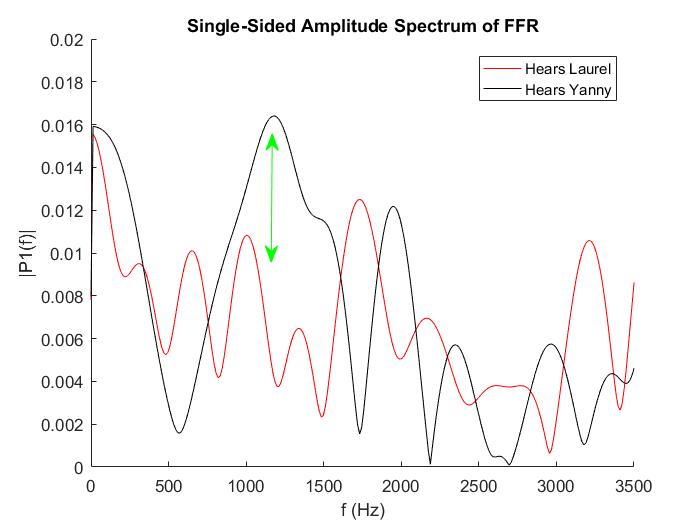

“I came in this morning and I asked my students [via email]: ‘Who is a ‘Laurel’ and who is ‘Yanny’?’” she told Salon. Musacchia sorted her students based on what they heard and found one student who had heard both. She performed brain scans while the student listened to the audio, using frequency following response (FFR) method. FFR involves using electrodes to observe how sound waves are reflected in the brain’s electrical activity. (If you’re curious, you can watch a YouTube video from Northwestern University’s Auditory Neuroscience Laboratory that explains how the scan works in more detail.)

Musacchia observed that the brain decides within a fraction of a second what it will hear (either Laurel or Yanny) and found the student could hear either “Yanny” or “Laurel” at will, with no changes to the audio clip’s pitch. (Many have observed that changing the pitch seems to force a change in one’s perception of the clip.)

“What I saw was that when ‘Yanny’ was intelligible, her brain response followed the frequencies of the Y sound,” Musacchia explained. “When ‘Laurel’ was intelligible, her brain followed the frequencies of the L sound.”

The difference in Yanny/Laurel perception relies on mid-range frequencies at the very beginning of the sound, she observed.

“What happens is that our brain decides within the first 100 milliseconds whether or not you will hear Y or L based on how well your brain responds to the frequencies between Y and L,” she added.

Musacchia shared with Salon her observational data that shows the difference in auditory brainstem response for the different words. The audio frequencies that the brain perceives actually look quite different depending on which word you hear, as you can see:

If the Yanny/Laurel debate comes down to how well your brain responds to the sounds of a Y or an L, this raises the bigger question about what we hear and why. Are our brains always deciding what we are going to hear just before it becomes intelligible?

“We use statistical probability to make almost all of our perceptual decisions,” Musacchia explained. “We hear what we have been trained to hear for the most part. We listen for speech sounds in a certain range.”

Perkins, like other audio experts, said she thought it could have something to do with those who have high-frequency hearing loss, something that normally occurs as humans age.

The New York Times has an interactive version of the audio where a user can modify the frequency range, but if Musacchia’s theory is correct, that tool could just be a subjective mind game, too.

Musacchia emphasized this illusion is not only about the frequencies but what word is focused on by one’s mind.

“Just like you are what you eat, you hear what you listen for,” she said.

Musacchia’s experiment today is just the beginning of a larger study. She said she’s going to conduct a study on this mystery and hopefully publish a paper on her findings, as there are still many unanswered questions.

“Some people can change their perception and some people can’t. What does that mean? What is it about those people who can change what they hear?” she asked.