Could it be that somewhere in this world, some diabolical supervillain is manufacturing a banned chemical and then releasing it into the atmosphere, part of a plot to eat away at Earth’s ozone layer?

That is what some scientists and researchers are speculating — although without the comic book twist. Indeed, an unofficial investigation has been triggered to solve this international mystery that resembles the work of a “Captain Planet” antagonist.

Scientists raised concerns on Wednesday when a report, published in the journal Nature, showed that emissions of CFC-11, a banned chemical that has been proven to be harmful to the Earth’s ozone layer, have increased 25 percent above average from 2002 to 2012. CFC is shorthand for chlorofluorocarbon; the chemical CFC-11 forms part of a group of pollutants that were banned under the 1987 Montreal Protocol, an international treaty created to protect the ozone layer.

“We’re raising a flag to the global community to say, ‘This is what’s going on, and it is taking us away from timely recovery of the ozone layer,'” NOAA scientist Stephen Montzka, the study’s lead author, said in an announcement. “Further work is needed to figure out exactly why emissions of CFC-11 are increasing, and if something can be done about it soon.

Scientists suspect that the unreported production might be coming from an unidentified source in East Asia.

“In the end, we concluded that it’s most likely that someone may be producing the CFC-11 that’s escaping to the atmosphere,” he added. “We don’t know why they might be doing that and if it is being made for some specific purpose, or inadvertently as a side product of some other chemical process.”

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, CFC-11 is “is the second-most abundant ozone-depleting gas in the atmosphere.” The chemical can still be found in older refrigerators — built before the mid-1990s — as it was used in foam insulation and appliances.

“I’ve been making these measurements for more than 30 years, and this is the most surprising thing I’ve seen,” Montzka told the Washington Post. “I was astounded by it, really.”

Montzka said if the source can be identified, and controlled, damage will be minimal. If not, it could lead to delays in the recovery of ozone layer.

The ozone layer is the shield that absorbs most of the sun’s ultraviolet radiation, and can be found in the lower part of Earth’s stratosphere. The ozone layer was discovered in the early 20th century. In 1987, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was enacted, a global treaty and commitment to phasing out chemicals like chlorofluorocarbons that appeared to be depleting the ozone layer.

Ozone — chemically, O3 — is a weak triple bond of oxygen atoms that can be easily torn apart by certain man-made chemicals. In the upper atmosphere, it forms naturally as a result of cosmic rays severing the bonds of atmosphere oxygen, O2, whereas at lower elevations it is an oft-harmful pollutant. The ozone layer serves an important role in deflecting ultraviolet rays and keeps the Earth cooler than it would be otherwise.

Ozone-depleting chemicals like chlorofluorocarbons are often measured according to their potential to split ozone molecules. In terms of that scale, known as “ozone depletion potential,” only one compound has a higher rating than CFC-11.

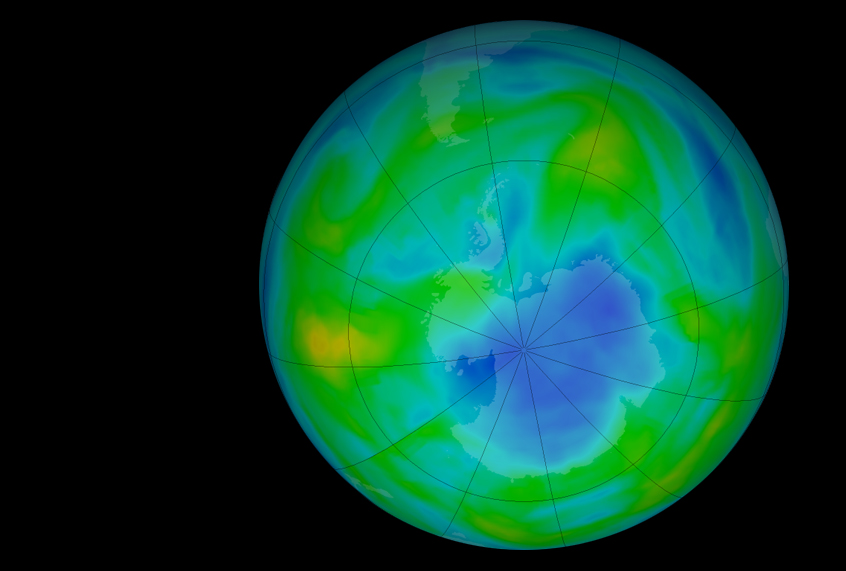

It was not too long ago that the situation with Earth’s ozone layer appeared to be dire. However, in January 2018, measurements showed that efforts to reduce ozone-depleting chemicals were having a positive effect in the ozone layer’s recovery. Indeed, NASA’s Aura satellite measured about 20 percent less ozone depletion during the Antarctic winter than there was in 2005.

“We see very clearly that chlorine from CFCs is going down in the ozone hole, and that less ozone depletion is occurring because of it,” lead author Susan Strahan, an atmospheric scientist from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said.

Scientists said the good news contributed to a better outlook for full recovery by mid-century.

“CFCs have lifetimes from 50 to 100 years, so they linger in the atmosphere for a very long time,” Anne Douglass, the study’s co-author, said. “As far as the ozone hole being gone, we’re looking at 2060 or 2080. And even then there might still be a small hole.”

But the latest news from this week could possibly slow that down that target. Overall, CFC-11 emissions in the atmosphere are still declining, but they are declining at a slower rate than they would be if there were no mysterious source producing the chemical.