The Brooklyn Museum’s current exhibit “David Bowie Is” brings David Bowie's work and spirit to life like never before with unprecedented access to his personal archive. The exhibit is open at the museum through July 15.

Matthew Yokobosky, chief designer and director of exhibition design at the Brooklyn Museum, sat down for "Salon Talks" this week to discuss the traveling multimedia exhibit’s last stop in Brooklyn and how it spotlights Bowie’s unorthodox and unique career through music, movies and pop culture.

This is a pretty exciting exhibit. It’s hard to get into and I enjoyed it very much. I was interested in the fact that it doesn’t follow the typical, chronological order that you’d expect of an exhibit of somebody’s life's work. It feels kind of more organic. Tell me about how the flow of this exhibit was conceived.

The first part of the exhibition is really about his history. Where he was born, what England was like in the 1950s. That goes up until his first hit, which is "Space Oddity" in 1969. Then from there it just breaks chronology completely and we go into an area where you learn about David’s songwriting techniques and about how he created the characters he did during the 1970s. Then, after that, you’re really hitting it into his media sound. You’re following his early music videos, his 1980s music videos which we all know, his career on Broadway, his career in film, and then of course, on stage -- we have a big concert moment at the end.

When I was there, I noticed that there was a wide range of visitors. There were people I think like me who are big David Bowie-heads and then there were people who were more casual fans. How do you balance the needs of both experts and newbies?

We spent a lot of time working on the labeling for the exhibitions. We have readers from the education department. We have readers who are arts scholars. We have people from visitor’s services. They all read the labels and information and they give a lot of feedback. We spent a lot of time working it out so that if you were new to David Bowie, you’d learn about his career. If you’re a big megafan like I think you are, we give a lot of new information also, a nice mix.

Watch the full interview on David Bowie

A Salon Talks conversation with curator Matthew Yokobosky

Yeah. It was fun. Audio is obviously a big aspect of this exhibit. You actually walk around with headphones on. Can you talk about how the sound was designed for this exhibit?

When you come to the exhibition, we give you a set of these amazing, sound-cancelling headphones by Sennheiser — plug, plug. They’re state-of-the-art headphones. And as you walk through the exhibition, the sound is changing with you. The audio system knows where you’re at. Most of the time it changes as you’re approaching a new video, which might be a documentary or it might be a music video. The trick was to have the songs on and off proximity to each other so that as you’re walking from one it would transition. There’s a lot of wiring in the floor, in the ceiling, to make all that magic happen.

The audio, as you said, is like the exhibition in that it’s not strictly chronological. It goes back and forth and it’s a bit more dramatic. One of the great features of the audio tour is that we had Tony Visconti, who produced 14 of David Bowie’s albums, do a mega mix for the exhibition. It’s the only place that you can hear it. He went back to the master tapes of 60 of David Bowie’s songs and went in with scissors and created this amazing mix track.

That’s amazing. I heard that and was impressed but I didn’t know that Tony Visconti did it.

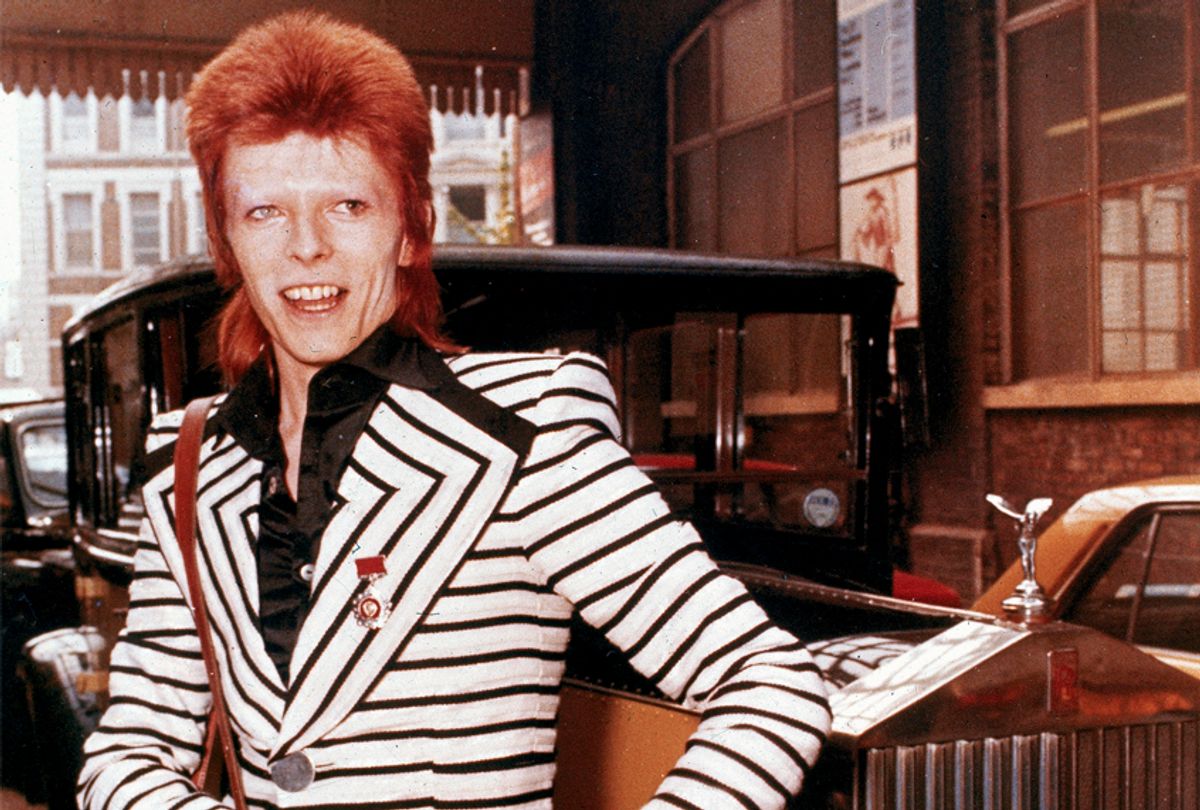

He came into the talk at the museum a couple of weeks ago and yeah, he really went into depths about what it was like working with David on all those major albums. Then last week, we had Mick Rock in, who took a lot of the early photographs. He was the official David Bowie photographer for 20 months during the Ziggy Stardust "Aladdin Sane" [period]. And this week, tomorrow night actually, we have Kansai Yamamoto, who’s flying in from Tokyo and was David’s costume designer for Ziggy Stardust to Aladdin Sane. We’re all hoping that’s a fantastic and interesting conversation.

A lot of his work is in the exhibit, right?

There’s eight costumes by Kansai in the show. When David became aware of Kansai, Kansai had just done a fashion show in London and he was supposed to be the first major Japanese designer to do a presentation in London. David saw the show and he went to a store that was selling Kansai Yamamoto and saved up his money until he could get one of the outfits. Kansai’s stylist found out that he was wearing Kansai and so they came to New York to Radio City Music Hall when David was premiering "Aladdin Sane" and they met backstage. And when David went to Tokyo, Kansai had made all these amazing outfits for him.

There’s so much about David Bowie. It’s very hard to narrow it down. But I was impressed by how much the exhibit kind of focuses on science fiction. How much did science fiction impact David Bowie’s work?

I think it’s both science and science fiction. In the late 1960s, the first photograph was taken of Earth from outer space, which was by astronaut Bill Anders and it was December 1968. No one had seen what the Earth looked like from outer space before. This was the first photograph and it was on the cover of the London Times in January and David wrote the lyrics for "Space Oddity," which was "planet Earth is blue / And there’s nothing I can do." It’s based on that photograph.

At that time he was also obsessed with Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey" and so "Space Oddity" is really just a word play on "Space Odyssey."

He invented that character of Major Tom, the astronaut at that point, which pops up again and again throughout his whole career. That was important to him. Stanley Kubrick's other movies, [such as] "A Clockwork Orange" were also very influential, especially on the costume designs. Then he kind of goes in and out of science fiction and fantasy throughout the career until you get to "Black Star," where, if you see the music video for "Black Star," you see the astronaut die. I think he’s a lot of an adventurer and wanting to just kind of explore and explore and fantasize about what the future might be like.

In other albums, for example, "Station to Station," he was a character of the train conductor at the beginning of it. A lot of this is all very interesting because David was also afraid to fly. Often times, he would choose to take a boat instead of flying in an airplane. And you’ll read different passages where sometimes he's OK with flying and other times he’s not. At the end of the Ziggy Stardust/Aladdin Sane tour, he was in Tokyo and everybody was flying back to London and he decided that he was going to take the train. He went on the Trans-Siberian railroad from Asia all the way back to London. It was very important trip for him because it went through to Berlin, which was where he ends up going in 1976 to make the Berlin Trilogy. But he first saw it on that trip in ’73.

The exhibit really does spend a lot of time on the Berlin years. Why do you think German culture had such a hold on Bowie’s imagination?

He first got interested in German film and theatre when he saw a production of "Cabaret" in London starring Judi Dench.

It must have been amazing.

Yeah. Sounds incredible. Right? I wish I was there. "Cabaret" is set in 1920s in Berlin and it features a lot of that chiaroscuro lighting, the white shirts with black jackets. And then, when he turned 27, there’s a singer named Amanda Lear who took him to see [the 1927 Fritz Lang film] "Metropolis" for his birthday. It’s kind of an interest in "Cabaret," kind of an interest in German expressionist film, and the design of those things really came out in a number of different ways for him.

When he was working on the "Diamond Dogs" tour, the set was based on "Metropolis," and we have a model of it in the exhibit. Later on, when he’s working on the Berlin Trilogy, he’s using a lot of the lightning techniques that you would find in these 1920s films. It was a big contrast, the German expressionist black and white with the more colorful, flamboyant Ziggy Stardust. Those were kind of two ends of that he was contrasting the whole time.

Bowie had a lot of collaborators over the years — we’ve already talked about Tony Visconti — including, obviously most famously, the producer Brian Eno. How do you incorporate this important aspect of his work? Because I feel like you always included other people as much as [the exhibit] could.

He was one of those people that always had their ear to the ground. Always trying to find out who was new, who was next, who was most interesting. With Brian Eno, the great thing about it was that Brian was also very curious all the time. They started working together because David liked his album "Discreet Music," which is just before he does "Music for Airports," which are just landmark albums. When they got into the studio, they just became a bubble, threw everything out the window and tried new things. They called up Robert Fripp and [said] do you have any interesting guitar things that you’re making? Do you want to come to Berlin and work with us? We’re in a studio working and this isn’t quite working out. So they used those oblique strategy cards which were designed for artists who are having artistic blocks to kind of try something new. It would be like using unexpected color or try two musicians swapping instruments and just play even though you don’t now how to play them.

Brian Eno brought a lot of experimentation into the process. But, I think overall David was always looking for something that was intriguing. He didn’t want his music or his look to just look like anybody else’s, he always wanted to have its own unique flavor and texture.

I don’t know if you’ve been following this story about hip-hop producer and rapper Kanye West who has been running around saying provocative things about Donald Trump. It reminded me of how Bowie would do some of that in the ’70s. He said he was intrigued by fascism. He would claim that he was gay when he wasn’t. Do you see similarities in their behaviors and do you think there’s anything we can kind of learn from that period of Bowie’s life?

I think people go through different phases in their life where they're interested in certain things and they don’t know why. You’re just kind of attracted to them and you want to read about it and explore it. I think people probably have that a lot with the internet today. It’s so easy if you find out about something you want to know about; you just Google it and it will come up. But it wasn’t always like that. Back in the ’70s, if you wanted to look and find out about something avant-garde or something that was kind of underground, you had to either go to a library with sunglasses on, or you had to be a little bit discreet. I think David was very interested in people mostly, and then he was always intrigued by how they worked. He was going to do a production of "1984" and couldn’t get permission to do that, but that’s very heavy book to work on.

I think he was definitely flirting with sexuality in the early '70s, both with his look and the things that he said, and there’s always a little bit of truth in everything.

It’s not always like a hundred percent or . . . it could be like 80/20 or something. Points of view changed, too. I mean —

Obviously, he regretted saying some things.

He regretted saying some things like Kanye West might regret saying some things later on. It’s tricky. But it gets you in the news. They’re definitely the things that people write about [which] come up again later. Certainly, later on, David I think regretted some of the things that he might have said in interviews. But sometimes he made up things for interviews too, like even if it’s about the most benign thing. He didn’t want to answer the same question the same way again. He would invent a new answer and those would become mythological and people would keep reprinting them and he would evidently just allow it to keep being wrong. He wouldn’t correct it.

That’s amazing and just so counter to a lot of how we think of celebrity working now. Everyone has been so literal now, I think.

Yeah. They try to [have] this façade of being down to earth and honest about every moment. Even reality TV is scripted. You’re not really seeing the Kardashians at home.

This exhibit has been around the world for the past five years. Why is it making its final stop in Brooklyn?

The exhibit started in London and its been to Paris, Berlin, Tokyo, Sao Paulo, Chicago, and at the beginning there was always a little bit of a thought that the exhibition would kind of begin where he began, and end where he lived at the end of his life. He lived in New York for 20 years, which might be the place that he lived the longest.

I went to see the show in 2013 in London. And I'm a big cheerleader of David Bowie. We started these discussions about it. David had done an acoustic guide for the Brooklyn Museum in around 2000. We had a big exhibit called "Sensation." He was the voice of the audio tour and that began our relationship with him. We were very happy to be the final venue for the tour.

Shares