Editor's note: This article originally appeared at FAIR.org. Republished by permission.

The presumption of innocence is supposed to protect those accused of a crime, in law and in the press. In corporate media, that rule also seems to apply to white people who report people of color to the police for doing innocuous things. As FAIR found, their identities are far more closely protected than those of people falsely targeted for “suspicious” behavior.

In the past few weeks, major news media have been flooded with coverage of incidents of alleged racial profiling and implicit bias — from golfers reported to police for playing “too slowly,” to picnickers fingered for using the wrong type of grill at a park. This coverage was prompted by viral videos and other social media posts released by the accused or by concerned bystanders, in real time or soon after these events occurred. The characters in these stories had one thing in common: The callers and officers involved were white; the alleged offenders, black or brown.

In a survey of coverage of four recent racial profiling cases, FAIR examined articles or segments in the New York Times, Washington Post and USA Today; on NPR, CNN, Fox, and the CBS, NBC and ABC evening news; as well as in major papers in the region where the incidents occurred.

These stories, while similar in content (often using the same quotes or incorporating Associated Press reports), didn’t lack for details. Those accused, police, witnesses, and corporate and institutional leaders were interviewed. Multimedia elements were included, such as smartphone, regular, and police body cam videos, audio from 911 calls, police reports and screen captures of social media posts.

But almost across the board, while the accused’s names and personal details have been made public, the accusers remain unnamed. Though equally newsworthy, they were allowed to retain their anonymity.

Stories and Coverage

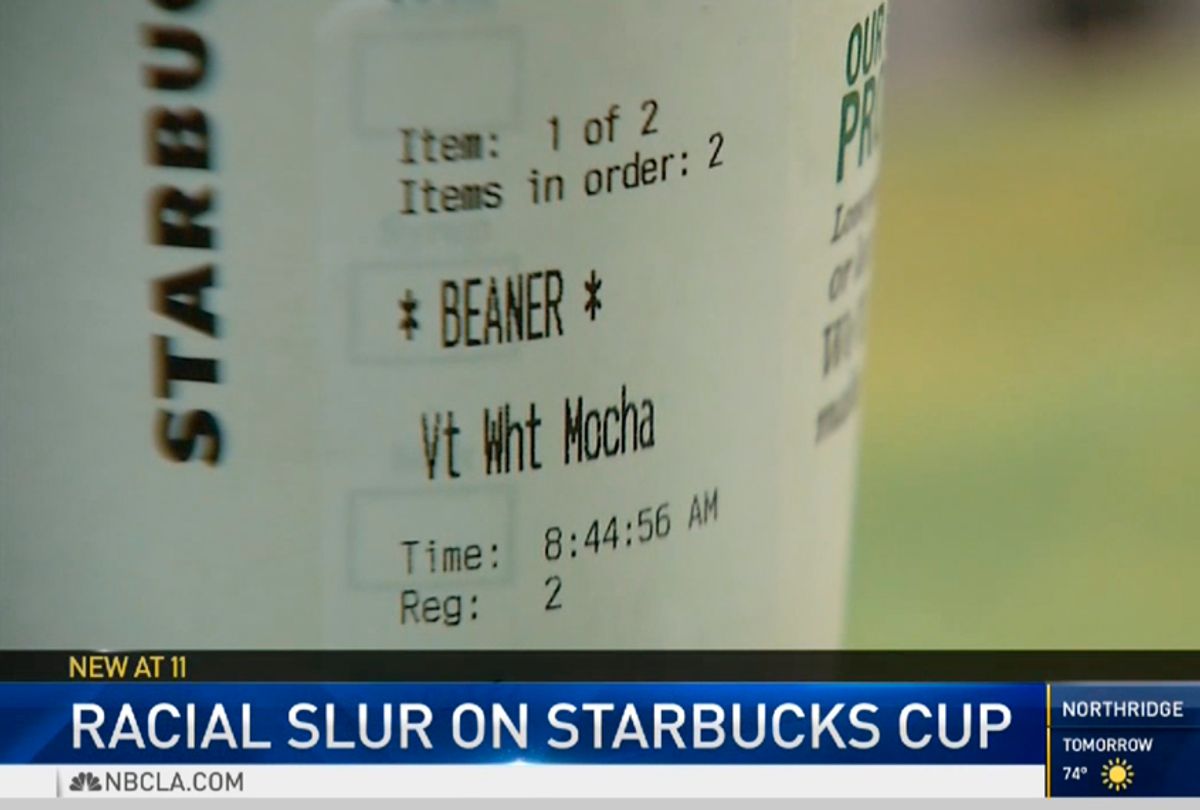

April 12: Donte Robinson and Rashon Nelson, two African-American entrepreneurs waiting for a colleague at a Starbucks in Philadelphia, were arrested by at least six police officers for “trespassing” when they failed to buy coffee before asking to use the restroom. In news reports, the white woman who called the police was identified variously as “an employee” (NYT, USAT, CNN, NPR, Fox), “white female employee” (WP), “Starbucks employee” (CBS), “staffers”/“a barista” (ABC) and “a manager” (NBC, ABC). The Philadelphia Inquirer also referred to “Starbucks employees.” Several follow-up stories about the manager’s later firing or resignation (Starbucks won’t say) called her only “the employee” (NYT) or “the manager” (CBS).

NBC News seemed to go out of its way not to reveal anything about the caller; its broadcast included audio from the 911 call in which her voice was intentionally distorted.

April 30: Brothers Thomas and Lloyd Gray of New Mexico, members of the Mohawk tribe and prospective students at Colorado State University, showed up late and spoke little during a campus tour. The Native American youth, dressed in typical teen garb of black T-shirts bearing metal-band logos, were patted down and questioned by campus police after a white woman on the tour called to report the “creepy kids” who’d made her nervous. Distraught, they missed the rest of the tour and drove home early.

In media, the caller was referred to only as “a parent” (NYT, CBS, CNN, USAT, NPR, WP), “a suspicious parent/concerned parent/unidentified mother” (ABC), “a mom/the nervous parent/the mother, who has not been identified” (CNN) or “a mother/the woman” (NYT, WP). The plethora of local coverage from newspapers and network news affiliates also cited only “a parent.”

The New York Times seems to have made some attempt to identify her, noting “her name was withheld by the campus police,” as did the Washington Post, which stated “the woman [was] identified in a police report as a 45-year-old white woman from Colorado,” and noted that “the caller’s name was redacted in the police report, along with the teenagers’ names.” So did a follow-up AP report published in the Denver Post.

Several outlets included audio of the 911 call, which appears to be redacted (there are moments of silence at points when the caller gives her name). It is unclear whether the edits were made by police or news outlets.

April 30: Filmmaker Donisha Prendergast and three colleagues, two of them black (as is Prendergast), were packing suitcases into their car after spending the night at an Airbnb in Rialto, California. They soon found themselves surrounded by patrol cars after a white neighbor reported that the house was being robbed. Police detained them and questioned them extensively before letting them go. Prendergast and her friends are now suing the department.

In coverage, the caller remained unidentified, except as a “neighbor” (NYT, WP, CBS, NBC, Fox — as well as USAT, which didn’t begin coverage till the lawsuit was filed); “someone/an elderly white woman” (CNN); “the caller/the reporting party” (ABC). (NPR did not cover the incident.) The local Los Angeles Times dubbed the caller “a woman.” Yet many reports made a point to specify the less-relevant detail that Prendergast is Bob Marley’s granddaughter.

May 8: Lolade Siyonbola, a black Yale University graduate student, fell asleep while studying in a dorm common room. A white grad student chastised her and called the police. The four officers detained her for more than 20 minutes to confirm her identity, even after she showed them her dorm room and unlocked the door. In all but a few cases, the caller went unnamed in news coverage, even though video images of the incidents showed the woman’s face.

Outlets called her variously “a white student/the student” (USAT, NYT, CNN, ABC, CBS, NBC); “another female student/the unidentified student” (CNN); “a white graduate student” (FOX, reprinting an AP report); or “someone/the woman” (NYT). No coverage was found for NPR. The local New Haven Register simply published a Yale press release, naming no one.

A notable exception was the Washington Post, which not only managed to identify the caller – one Sarah Braasch — but also included Siyonbola’s allegation that Braasch had a history of calling cops on unfamiliar African-Americans. The Root, citing a report in the Yale Daily News, subsequently confirmed an incident in which Braasch had called police on a different black student, Jean-Louis Reneson, who’d gotten lost in the dorm and asked her for directions. (ABC News also referenced the previous incident, without naming Braasch.) Contrast this with NBC News, which went so far as to redact Braasch’s name from the image it included of Siyonbola’s Facebook posts on the incident.

Problems With Privacy

The lack of ID is especially odd considering these outlets didn’t break these stories; they could have added value to the social media reports by not only identifying the persons responsible but obtaining their take on the incidents. Starbucks, Airbnb, Colorado State University and the Rialto police department all issued elaborate statements and/or apologies quoted in these stories. Critics have demanded the 911 callers apologize as well (or even be charged themselves) — issues the unnamed callers will never have to address.

The trend of allowing callers to retain their privacy is problematic for several reasons. First, it fails to follow one of the basic tenets of reporting, omitting the first of the proverbial five Ws (who, what, where, when, why). Key players in these stories – the individuals who triggered the incidents by contacting authorities – remain mysterious. Confirming a caller’s identity also helps to establish that person’s credibility, as well as their motivations.

Moreover, as thinkpieces and op-eds in these outlets pointed out in subsequent coverage, racial profiling and harassment are an ongoing problem for people of color. Such incidents can lead to loss of innocent lives at the hands of armed police, as the families of Philando Castile and Sandra Bland know all too well. Failure to attempt to explore and publicize the identity and background of people who overreact to the presence of people of color means such injustices will continue to happen — not to mention the waste of police time and resources better spent pursuing actual criminals.

Implicit Media Bias?

What’s behind this trend? It seems the media are substituting the news judgment of the police, Starbucks and two universities rather than retaining journalistic independence, allowing institutional protocols to limit coverage. They also appear to allow the privacy preferences of the callers to influence the stories, implicitly giving them the benefit of the doubt. For example, NBC News’ piece on the Yale incident opened with a voiceover asking, “Racial bias or an honest mistake?”

And from the headlines and framing of certain stories, we might also surmise that some outlets felt the callers’ and cops’ actions were justifiable: “Officers in Starbucks Incident ‘Did Absolutely Nothing Wrong,’ Philadelphia Police Chief Says” (Fox, 4/12/18); “Police Chief Defends Officers’ Actions in Viral Starbucks Arrest Video” (CBS, 4/12/18). Similarly, in the Airbnb case, we saw headlines such as “Video Shows Black Airbnb Guests, Police Joking About Call” (New York Times, 5/8/18) and “California Police Release Bodycam Footage, Defend Detaining Bob Marley’s Granddaughter and Others” (San Jose Mercury News, 5/9/18).

How to Do Better

Veteran journalist Aly Colón, a professor of media ethics at Washington and Lee University and formerly director of standards and practices at NBC News and Telemundo Network News, explains that those who, rightly or wrongly, become the subject of police action are considered public figures, but even private parties involved should be named whenever possible.

“There’s an axiom, ‘Make sure you get the name of the dog,” he says. “Meaning when you go into a news story, get the names of everybody.” Colón told FAIR, “It doesn’t behoove journalists to leave any questions that they can answer unanswered.” Without these perspectives, “it runs the risk of diminishing the credibility of the story.”

In this era of social media trolling, people have a right not to talk to the press. But there are ways to obtain a name beyond relying on callers to out themselves or institutions to release their identities. For example, some stories on the Airbnb incident quoted the owner of the house, Marie Rodriguez, who defended her neighbor’s actions. Surely Rodriguez knew this caller’s name. If a reporter asks and is unsuccessful, it’s customary to indicate what attempts were made, or why identities were omitted or redacted.

(As this story was being edited, the identity of a lawyer, Aaron Schlossberg, who harassed a New York restaurant patron for speaking Spanish on May 16, was included in May 18 stories by CBS News, USA Today and the New York Daily News, among others. On May 15, The Root published a piece on “BBQ Becky,” the white woman who called police on black Oakland picnickers. She’s environmental scientist Jennifer Schulte. In both cases, the information came thanks to tips from social media users, subsequently verified by the news outlets. )

In many ways, the press response to recent events is promising. There has been a steady stream of follow-up articles on these profiling incidents as well as commentary on racism, law enforcement and justice, helping to sustain the public conversation on vital topics. Yet the identity of three of four 911 callers remains a mystery. It is time to name them — not so much to shame them, but to fulfill the news media’s role in advancing the public’s right to know.

There is also the matter of accountability. In an opinion piece for the Washington Post on May 16, professors Stacey Patton and Anthony Paul Farley wrote:

It is a crime to file a false police report. When places of public accommodation enlist the police to remove people based on race, the owners and managers should be investigated and prosecuted for filing false police reports. At the Philly Starbucks, the Yale dorm, the golf course or the Oakland park, the police investigation should have focused on the frivolous and possibly criminal abuses of the 911 emergency system rather than on the people who were doing nothing wrong when someone called about them.

And that should be the focus of the press as well.

Shares