AT&T has given companies a lesson on why investors increasingly are seeking information about corporate political spending.

For five years, investors have called on AT&T to tell them how much it was spending to lobby politicians at the state and federal levels. AT&T refused.

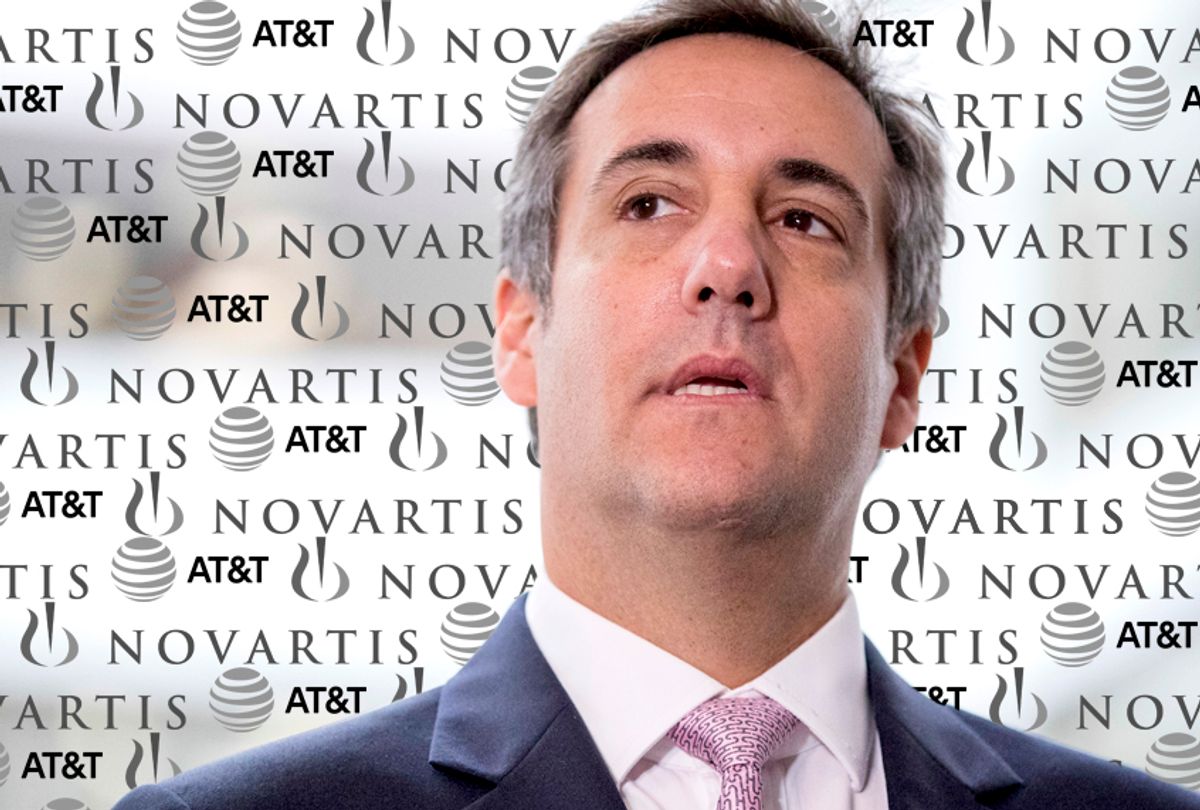

Now, the company is deeply mired in a self-inflicted legal and reputational disaster through the now disclosed $600,000 in payments to President Donald Trump’s personal attorney, Michael Cohen. The leaked information has led to complaints being filed about possible Lobby Disclosure Act violations, the resignation of the head of the AT&T lobby shop and a torrent of negative press.

All this leaves the investors who asked AT&T to improve its lobbying disclosure (and were rejected) dismayed that AT&T’s lack of transparency, disclosure and oversight contributed to this public relations (and shareholder value) fiasco.

Political spending has become more of an issue since the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court’s overreaching decision in Citizens United, which enabled corporations to spend unlimited sums to influence our elections. Since then, many have pushed the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to create rules that would require public companies to disclose their new political activity.

The call for action at the SEC has been historically loud, with the call for rulemaking receiving an all-time record number of 1.2 million public comments. Investors have exerted similar pressure on a company-by-company basis.

Companies engage in two categories of activity: campaign spending (newly allowed by Citizens United to be undisclosed as long as the money routes through so-called “independent entities,” like trade associations or nonprofits), and lobby expenditures. For both types of political activity, shareholders have called for their companies to disclose, bolstering the need for SEC action.

Just two weeks ago, on April 27, AT&T shareholders voted on a proposal asking the company to provide a report on its federal and state lobbying, including board and management oversight. Walden Asset Management, Zevin Asset Management and others filed the proposal.

It asked AT&T to publish an annual report containing the company’s policies and procedures for both indirect and direct lobbying as well as any grassroots lobbying communications. AT&T’s board opposed this, saying that “The Board is confident that the Company’s lobbying activities are aligned with its stockholders’ long-term interests.”

Despite the AT&T board’s opposition, the proposal received 34.26 percent of the votes cast. This was the fifth year in a row that the shareholder proposal for lobbying disclosure and oversight was voted on, so AT&T cannot say with any credibility that it was unaware that many of its shareholders were concerned of the potential risks that its lobbying could engender. With the damaging disclosure of the Cohen payments, AT&T is getting a crash course on the pitfall of the lack of oversight on lobbyist expenditures.

Companies succeed or fail by their reputation, and a trustworthy reputation leads to strong shareholder value. One way to prove corporate integrity and reputational soundness is to be transparent. Without that transparency, corporate lobbying, when exposed, can present real reputational risk that harms the corporate brand and in turn, investors.

AT&T was asked repeatedly by its investors to get out ahead of the sort of situation the company now is embroiled in. AT&T and its board have learned this lesson the hard way; it should immediately shift to supporting the transparency that could have minimized this crisis.

Shares