Outside of the White House, it is difficult to find anyone who thinks Trump’s negotiation for a fairer, understandable and predictable China trade deal that addresses the long-term complaints has worked.

Indeed, what started as a thunderous call for tariffs and counter-tariffs has disappeared for a temporary, if vague, set of promises by China to buy a lot more American agricultural goods.

Still, Trump is heralding the vague deal as a big win, particularly for himself.

It’s an interesting case study: Every time one looks for information on one aspect of the deal negotiations, something sticks out on another.

As a candidate, Trump called out China repeatedly for manipulating currencies, for stealing American intellectual property, for putting onerous burdens on American businesses wanting to manufacture or sell in China and for creating conditions of an anti-American trade imbalance that he has exaggerated to be $500 billion a year. It is closer to $375 billion per year.

With tariff announcements from each side as place-setters for negotiations, there has been nervousness from wide varieties of industries, countries, markets and everyday American consumers about the results. These exchanges have wound up, for now, with vague promises that include the U.S. promising to rebuild the Chinese telecom ZTE, an intention to buy “a lot” of American products that might help Trump to say that the yearly balance of trade has been reduced and no apparent progress on any of the structural issues that allegedly were present at the start of these China problems.

Andrew Ross Sorkin of The New York Times was almost wistful about it all: “Investors clapped their hands—and scratched their heads. What had just happened? Didn’t Mr. Trump complain just last month about ‘China’s unfair retaliation’ intended to harm American farmers and manufacturers? And didn’t his Treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, explicitly say that if China didn’t bow to American demands to reduce the trade surplus by $200 billion, ‘There is the potential of a trade war’? Now, Mr. Trump is heralding a vague deal—one with no specifics or dollar figures—as a big win.”

“To those on Wall Street and other executives who make a living negotiating, the deal struck by the president who wrote ‘The Art of the Deal’ doesn’t look too artful. Not only that, the deal—to the extent there is one—raises all sorts of questions about Mr. Trump’s ability to extract concessions in future negotiations,” said Sorkin.

Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., said, “China is winning the negotiations. Their concessions are things they planned to do anyway.”

If you did think you had a handle on it all, Trump confused understanding by a new tweet yesterday, saying: “Our trade deal with China is moving along nicely, but in the end we will probably have to use a different structure in that this will be too hard to get done and to verify results after completion.” No one could know what that means.

The Times’ Keith Bradsher, who has been covering business affairs in China for 20 years, said China called Trump’s bluff, leaving Washington with the tariffs shelved and a pledge to rebuild ZTE while having given up little in return. He said China had spurned the Trump administration’s nudges for a concrete commitment to buy more goods from the U.S. and avoiding limits on its government-led efforts to build new high-tech Chinese industries.

Among other things, it seemed to come as a surprise during the negotiations that so much of the ZTE supply chain actually had involved American goods and manufacturing itself.

Any idea of a trade fight is far from over. We can ruin each other’s markets and make whole industries vulnerable to specific trade rules. Bradsher argues that a confident China could be more than a match for divided American negotiators who have made often discordant demands.

Trump, who proclaimed earlier this year that “Trade wars are good and easy to win,” and his advisers may find that extracting concessions from China is much harder than they expected. Bradsher reported that China’s propaganda machine took a victory lap after the talks, proclaiming that a strong challenge from the U.S. had been turned aside, at least for now.

Sorkin noted that Trump’s “negotiating playbook is by now pretty obvious: Start with a headline-grabbing demand, beat chest loudly, then accept whatever is actually practical and call it a win. In negotiating parlance, such a strategy involves trying to ‘anchor’ yourself to an extreme position, knowing that the real goal line is something much less than what you’ve said. But Trump seems to routinely unmoor himself, leaving him exposed to the whims of those on the other side of the negotiating table.”

The negotiations also displayed internal chasms within the U.S. delegation between Treasury’s Mnuchin and Trump’s personal trade guru, Peter Navarro. The men apparently profanely went at one another in a hallway outside the negotiating room.

Larry Kudlow, the president’s top economic adviser, put a $200 billion dollar a year figure on the Chinese commitments at the table, only to have to retract it when the Chinese objected. The U.S. team is split with more nationalistic or more globalist philosophies.

The U.S. negotiators, including Trump, have shifted demands and struggled to send out a consistent message. Trump seems to bend all of the conventional rules of negotiation.

Chinese and American officials did exchange lists last week of extra goods that China might buy to narrow the deficit, but China only committed to continue buying ever-rising quantities of American food and fossil fuels, a position reflected in the joint communiqué issued at the close of the talks.

The details for other items are yet to be worked out, which is why the Commerce secretary, Wilbur Ross, is headed back to China to clean up after all the negotiators did whatever they did.

One example: China has carried out a pledge to cut tariffs on imported cars and car parts. But the American auto industry and its workers might be unimpressed. China’s Finance Ministry said it would trim tariffs on imported cars from 25 % to 15% of their wholesale value. It also cut tariffs on imported car parts, reducing them to a standardized 6%. Chinese tariffs on parts currently average about 10 percent and range from 6% to 25%, depending on the category.

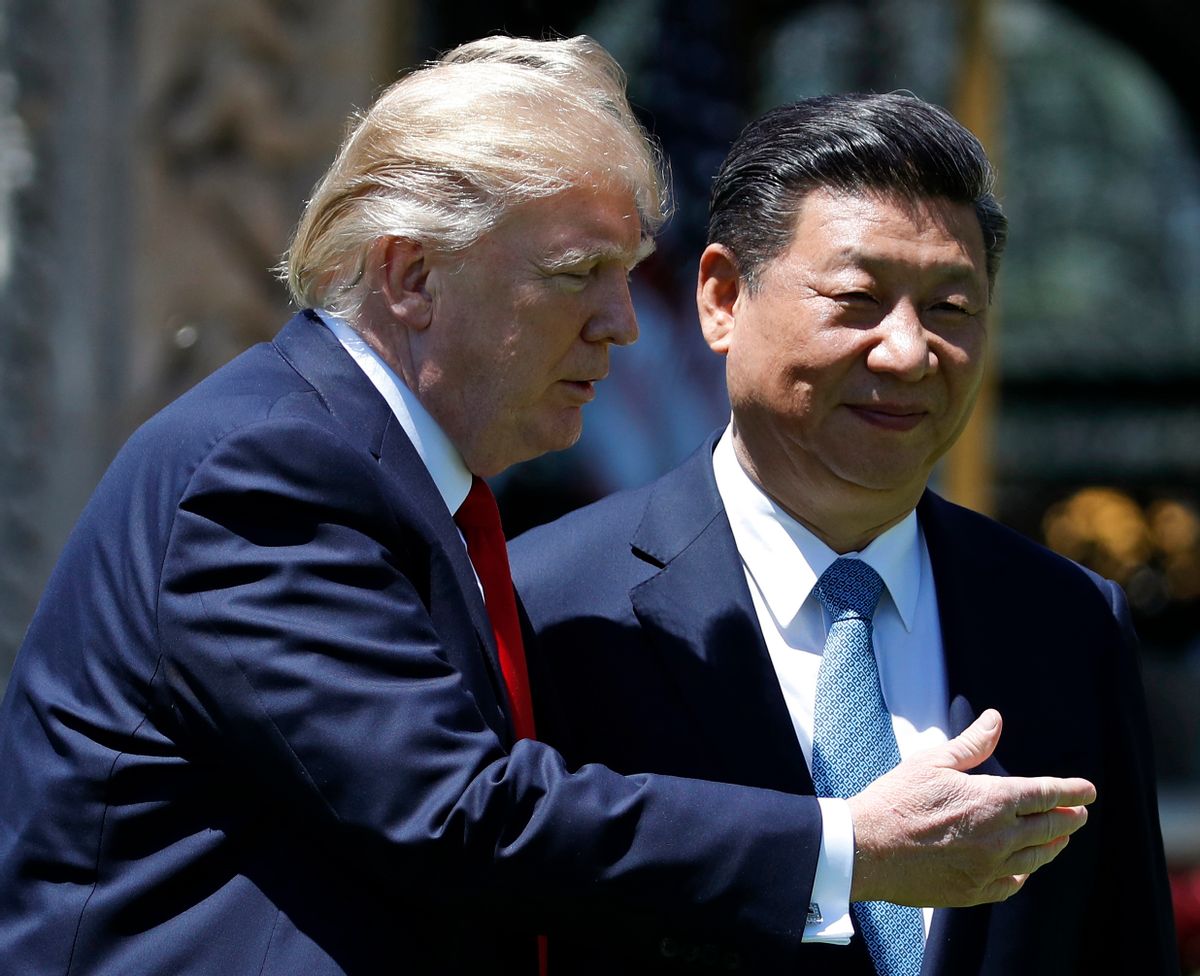

The U.S. has also explicitly tied the trade talks to its efforts to negotiate with North Korea. Chinese leader Xi Jinping met with Kim Jong-un, North Korea’s leader, in northeastern China about two weeks, ago. It is unclear what they discussed, but Trump today canceled the summit meeting with Kim that he had planned for June 12.

At the end of the day, on the way to celebrating either no tariff war or expanded American business or some kind of international agreement, one does wonder why this process has felt so shaggy in its execution.

Shares