As we made the short walk to the park from Chicago’s Old Town—the neighborhood that was the heart of local hippie culture—our balloon of expectation deflated. Where were all the people? Okay, maybe a half-million had been a bit optimistic, but there weren’t a tenth that number in the park on a Sunday afternoon. Or even a hundredth. Instead, if you counted (and you could have), there were perhaps two thousand milling around the southwestern sector of the park—the Yippie enclave—a motley assemblage of tie-dyed freaks, bushy-haired hippies, curious high-school kids and a few buttoned-down radicals sitting or strolling, looking at each other, waiting for something to happen. We would later learn that, amid the few, there were plenty of undercover agents who had infiltrated the gathering and might later incite some aggressive action.

Instead of the high drama anticipated, the early part of that afternoon was closer to the era’s cliches of summer in the park—mellow, groovy, filled with good vibes. Allen Ginsberg sat in the lotus position under a tree amid the grassy expanse, leading a circle in the chanting of “Ommmmm.” (He would subsequently chant for seven hours, as the vibes turned increasingly sinister.) The two wild-haired, flashing-eyed Yippie masterminds—Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin—put a brave face on the meager turnout, smiling in the sunshine as they scurried and schemed, darting this way and that, recognizable from their pictures in the newspapers as “leaders” of whatever was about to transpire. Yet few of the locals in the park that day seemed to show much interest in following the lead of these manic East Coast activists. Rolling Stone had warned us.

Anyway, where was the music? Where were the Dead, the Stones? Where was Country Joe? From what we could see, the Festival of Life had been a pipe dream. There was no stage, no amps, no mic.

It wasn’t until late afternoon that one band would be brave enough—or foolhardy enough—to attempt to spark a revolution in Chicago and risk the wrath of the police. One band not only matched the anticipatory hype, but exceeded it. One band would transform itself into myth, embodying the chaos of cultural uprising for generations to come.

“Brothers and sisters, are you ready to testify? I bring you a testimonial: the MC5!!!!!”

Let me admit, brothers and sisters, that I can barely remember significant details of the day that I’ll never forget. Impressions dissolve in the haze of marijuana from that sunny summer afternoon in Chicago, while the subsequent passage of almost four decades has sacrificed more to the mists of memory. Yet the imprint remains indelible. Like a car crash or a blitzkrieg, it divides my existence into Before and After. For nothing was more important in my eighteen-year-old life than rock and roll. And rock and roll would never be the same for me after I saw—experienced? endured? survived?—the band that would change my life.

No, I’m not going to pull a Jon Landau. I won’t claim that I had a vision of rock’s future when I first withstood the aural assault of the Motor City Five, whose sound and fury disrupted that idyllic Sunday in Lincoln Park. Contrary to common legend, the MC5 didn’t spark a riot with their free concert on the eve of the 1968 convention. They simply lit the fuse, escalating the tension, energizing the crowd to a fever pitch of musical militancy as the police encircled the park, with their riot gear and billy clubs, maintaining a stone-faced vigil.

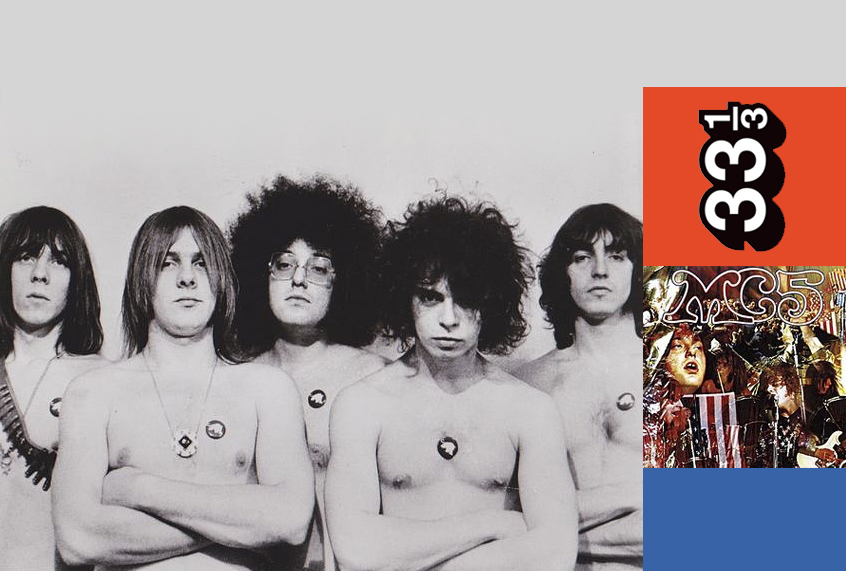

I can still see the orb-like Afro of the lead singer as he badgered the crowd, pointing his finger, thrusting his fist, working his feet like a speed-freak James Brown. I would later know him as Rob Tyner, but all I knew at the time was that he was crazy. But not as crazy as the two guitarists, the ones I would later know as Wayne Kramer and Fred “Sonic” Smith, both brandishing their instruments as if they were lethal weapons while swiveling their hips, arching their backs, flailing their arms, kicking their legs.

All this over a rhythm section that left no space unfilled in its relentless propulsion, a bassist and drummer—Michael Davis and Dennis “Machine Gun” Thompson, I would later learn—less concerned with staying within the pocket than obliterating that pocket. When a low-flying surveillance helicopter buzzed the band, the whoosh and whirr of its blades didn’t interrupt the music, but enhanced it. Even the occasional roar of a cop’s motorcycle seemed like part of the musical gestalt, amid a crowd that fully expected that musical chaos would lead to physical violence. This wasn’t a rock band; it was a street fight. This wasn’t a concert; it was a battle zone.

We had been waiting for something to happen, even desperate for something to happen. The MC5 were what happened. We hadn’t known what to expect, but none of us had expected the 5. Almost none of us had ever heard of the band, except those who had made the drive from their native Detroit. Though we thought we’d been ready for anything, the frenzied, ear-splitting performance left most of us shell-shocked. It was a musical mugging so far beyond the realm of expectation that it would take years before punk or metal would provide some sort of frame of reference, though no punk or metal band would ever match the galvanizing force of the 5.

Despite the band’s railings against the “pigs” and exhortations to “kick out the jams,” the music didn’t rouse the rabble so much as render us benumbed or bewildered, confused or bemused. In the wake of that aural assault, the most prevalent reaction was What was that?—mouthed more than heard, with the aftershock continuing to ring in our ears. When Abbie Hoffman announced that the cops had pulled the plug on the festival, as if there was anything on the bill beyond the half-hour blitz by the MC5, an uneasy calm returned to the park, mixed with a sense of foreboding, as the crowd waited once again for whatever would happen next.

It wouldn’t transpire until well after dark, when the 5 were long done and my brother and I were long gone—back to the domestic safety of the suburbs—as those police on the park’s periphery invaded what had once been a peaceful, even playful gathering. By enforcing the park’s 11 PM closing time and camping prohibition, they sent a few thousand protestors fleeing into the streets with nowhere to sleep. As a prelude to four long days of billy clubs and tear gas, no band could have better anticipated the street fighting to come than the MC5.