On July 12, 1999, Junot Díaz found himself in a place few writers will ever even dream of finding themselves: on the front cover of Newsweek. Díaz is one of three figures standing in a blue sky dressed with clouds.

On the far right, the largest figure — crossed arms, a flat expression wrapped inside a muscular mass of face, reserved, triumphant, is boxing star Oscar de la Hoya.

In the middle: dyed red-black hair falling down in strands, hips curved around the large white letters, "U.S.," the only one of the three whose body faces the camera straight on, and the only one who seems to know how to look at a camera on purpose, Shakira.

And finally, the figure set back the most, his face ornamented with a goatee, a pair of black thin-rimmed glasses and a dry, distant look: Junot Díaz.

Together, they create the human backdrop for the edition’s title, which reads like a declaration: "Latin U.S.A.: How Young Hispanics Are Changing America."

I flip inside and find the title story, then read the first line out loud: "Hispanics are hip, hot, and making history." Much of the rest of the article reads this way, like an advertisement, and struck through with a certain unmistakable hunger. It is an old tired script now, but perhaps in 1999 it rang new, fresh, sellable. At the end of the first paragraph, these hip hot Hispanics are likened to a wave.

There is a world to uncover here, so much to put under a cultural microscope. But mostly what I want you to pay attention to is this: What is Junot Díaz doing there, in that sky?

By the time this picture was snapped, de la Hoya had won boxing titles in multiple weight classes, had taken down stars like Pernell Whitaker and Julio Cesar Chavez, had represented the U.S. in the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games and had come back a household name. In 1999, Shakira was riding on the high of her fourth studio album, "Dónde Están Los Ladrones," an album that earned her $10 million in worldwide sales, a Grammy nomination and a feature recording on "MTV Unplugged." Months before appearing on this cover, she had announced plans to work on her first ever English-Spanish crossover album (and oh, what a crossover it would be).

Then there’s Junot. In 1999, Junot Díaz is a 31-year-old writer with a recently published collection of short stories, "Drown," and a novel in the works. "Drown" does well, probably as well as a first book could hope to do: a shining New York Times review by David Gates, a slew of literary buzz, two pieces featured in America’s Best Short Stories. And yet, Díaz was a young writer. His best known works, his Pulitzer Prize, the vast majority of his literary accolades were all years away, part of a distant future. Yet there he was in 1999, suddenly, if not all at once, planted in that sky. When I find the photo researching Junot Díaz’s rise to fame, I wonder why he is there, and I wonder what it might have to do with that hunger, a hunger for a Latin U.S.A., and maybe for a figure in that landscape who isn’t known for shaking their hips or knocking people down in a ring. Instead, a writer: male, genius, able to speak the stories of his world for anyone who wants a peek in.

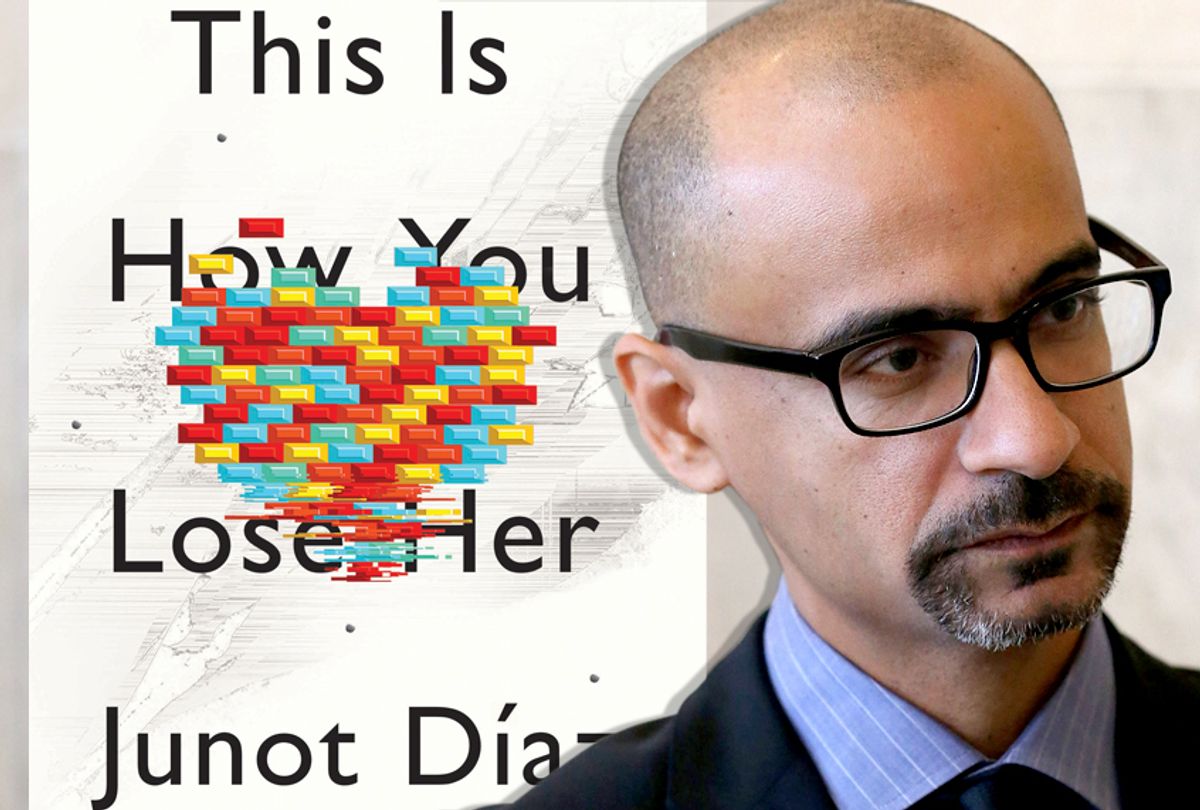

And yet we can’t be unfair. It wasn’t just Newsweek and The New York Times. It wasn’t just White Liberal America who was hungry for Junot Díaz. In high school, when a friend left a copy of "This is How You Lose Her" in my backpack, resting against my biology textbook with a yellow post-it note pressed onto the front cover that read I think you need this, he was right, I did need it. Sixteen-year-old me, full of hungers, ready to place Junot Díaz in my own clouded sky.

I am trying to write about Junot Díaz; his books, his harm, and what all of it might mean for a Latinx book lover and a young man committed to the responsibility we all share in this moment of standing against violence.

Over the past several weeks, a growing collective of women, mostly women of color, have come out accusing Díaz of sexual misconduct, abuse, assault and bullying. I stand by these women. I believe their accounts. I believe their descriptions of his violent behavior to be true. And I believe in the need for real accountability.

These beliefs all point me in one direction, towards a question that has silently inhabited my life since the news broke: How do men, particularly Latinx men who saw Díaz as a hero, move forward in solidarity?

I'm trying to piece together answers to that question. Unsurprisingly, it all starts here, in that sky, our national sky and my own male sky, trying to understand what Junot Díaz was doing all the way up there in the first place.

*

Here is the short story of how Junot Díaz ended up in my sky.

In 2013, I was 16 years old, and everything in my life seemed to be breaking or moving. My parents split up, my first relationship was in pieces, my sister moved to college, and there I was, standing in the wake of it all, struck by a grey, dull feeling I would later learn has a name: Depression.

Reading is a collision — the sometimes explosive meeting of a particular book and a particular moment in a human being’s life. It's hard to piece apart the exact physics of any such collision, but in the case of me and "This is How You Lose Her," I will try. Some books meet you as companions, and yes, in Díaz's protagonist Yunior I saw a young Latinx male artist struggling with the broken pieces of family, struggling with mental health, with his weight, with the project of masculinity. I identified. It helped.

But there were other things, too, other forms this collision took. For me, "This is How You Lose Her" fell into my hands most of all as a map. All the simultaneous internal and external damage of being a man mapped out naked and bare. A set of codes I could and would use to start to make sense of all the male bullshit in my life, all the hurt it had caused. The honesty of its coordinates spoke to me.

What happened next? I clung to that book like I had never clung to a book before. I carried it everywhere, like an asthmatic carries an inhaler, and read it over and over. You wouldn’t catch me without it: in classes, at track practice, at a party, sleeping in my bed — it was never more than 100 feet from me. Then I burned through his other books, started listening to his lectures on YouTube, taking notes in the back of my journal. Notes on “the predatory nature of privilege” and on “racially organized sexual economies” and on “decolonial love.” Somewhere along the way, my heart had quietly taken to building its very own Junot Díaz altar.

Looking back at a journal from that time, I read my own account of what it felt like. I call it a grayness in me, building and building until it felt like I could explode, until it was all I could do to try and put it somewhere. In the search for that somewhere, I decided to write a song (I had taken to studying and practicing music with some discipline back then, and had the basic tools). My silent hope, not written in my journal but remembered, was to speak back to, in some way, the book that had meant the universe to me, to craft my own side of the collision.

I ended up writing a song with four vocal parts, set to the epigraph of "This is How You Lose Her," an excerpt from "One Last Poem for Richard" by Sandra Cisneros. I called my song "One Last Song for Richard." By some stroke of magic, charm and pity, I was able to convince my high school choir teacher to let us sing the song in class. Then I got a recording at our concert, and with little forethought I posted the song on YouTube. One day, the idea landed in my heart like a promise: Send the song to Junot Díaz.

My email was short, a link to the song and a quiet thank you for what his art had meant to me. Then, the act of universal wonder: a note from Junot Díaz landed in my high school email inbox. He told me my art is wonderful and asked me questions about my life (my life!!). We began to talk. All of a sudden, a whole set of miraculous things happened. Junot posted my song on his Facebook page, called it extraordinary. Strangers began to comment on the song. Sandra Cisneros wrote me an email thanking me. I emailed Brown, my dream school that weeks ago had sent me a waitlist letter (which basically read: you have some things going for you, but no), and told them what had happened. They accepted me less than a week later.

I told Junot Díaz I wanted to be a writer. He told me not to major in creative writing in school but to focus on my music and my life, that that would help my writing the most. I packed my bags for Providence intent on keeping his promise, the architecture of my Junot altar as strong as my own bones, and as firmly lodged inside of me.

This is how much Junot meant to me. He wasn’t just a hero of mine. He was the centerpiece of my sky.

For years I’ve kept that story wrapped, packaged, accessible at any time. I used to call it: the most awesome thing that ever happened to me, because it was. Such a finality to what I thought that moment had meant. So untouchable, in my mind, by any goings-on in the present — whatever shit was happening in my life, I could go back to that story, hold it in my hands, think damn, that was awesome. Junot Díaz, that man I had placed in the sky, reaching right into my life on the ground, saying you matter.

Here I am now, unwrapping, pulling apart at the wreckage of it all. Salvaging what can be salvaged, and leaving what must be left to float away. I wonder about the space between who Junot Díaz is, and who the 16-year-old me needed him to be. I trace the outline of that space, measure its coordinates on a new map. Could this be my task? To fill that space with something different, something new?

*

Maikerly and I have dinner to talk things over — her MCAT score, my relationship and what’s been going on with Junot Díaz. Maikerly came over from the DR when she was a kid, and somehow we both ended up at Brown. Now in our senior year, she’s my friend and my sister, equal parts. Together, we are mourning our hero.

And he’s Dominican. A Dominican getting big like that. That’s fucking rare. Her voice is cracked with anger. We’re sitting in her kitchen, scrolling through Junot Díaz headlines like footage of a natural disaster.

It is an anger connected to worlds Junot Díaz stands for. Not just Latinx, but Caribbean, Dominican, of African descent. It is an anger I can respect but cannot fully understand.

We are two 22-year-olds born in 1996, the year Junot’s first book was published. Our whole conscious lives have been lived with the fixture of the Latinx male genius writer who seemed to tell our truths.

We read the stories, though, all of them. The one of him asking a woman to clean his kitchen, the one of him asking a student in his program to keep their relationship quiet. The one of him kissing a grad student forcibly. So much of him and these women, shaped by asking, then sometimes shaped by not asking at all.

We read reactions. We find inspiration in the bravery, the honesty, the vulnerability of so many others.

Some say Junot Díaz is a bad writer, though, and I wonder, not about the validity of such an assertion, but about its convenience. It's easy to deal with a harmful person who is also a bad writer, easy to place that person. But what do we make of a broken, harmful person who is also a good writer? What do we do with the possibility that his brokenness, his intimate terms with harm, is also what makes his art possible, or powerful?

These are questions that inhabit the air around us, floating with the sharpness of a knife. For now, we let them be. Maikerly wants to become a doctor, and I want to be a high school teacher. I joke: Maikerly, maybe you could be my new hero. Her laughter comes out in bursts, spilling into the air around us until everything feels less sharp. We cook dinner, and we don’t talk about Junot Díaz again.

*

It’s 2013, and it’s raining. I am lying on the floor of my living room, back to the sky, re-reading "This is How You Lose Her." The first story, "The Sun, the Moon, the Stars," begins with lines I’d long ago memorized: “I’m not a bad guy. I know how that sounds—defensive, unscrupulous—but it’s true. I’m like everybody else. Weak, full of mistakes, but basically good.”

All at once, the pages disappear. My sister Livia has pulled the book out of my hands and is holding it in the air like a toy I wasn’t supposed to be playing with. "This book is so sexist," she says, "I don’t get why you’re so crazy about it." I reach for it — my inhaler — but she is already by the stairs taking the book away.

Trying to find my breath, I offer what I know to be true. "That book means everything to me."

Back then, with all the forthrightness of a little brother, I had come to one conclusion about my sister’s opinions on Díaz: she doesn’t get it. She must be missing something. How could something so impactful to me be so easily dismissible to her. She’s wrong.

Now I am doing away with those certainties and wondering what it would mean for both of us to have been right.

For me, "This Is How You Lose Her" was that map, that everything. My own toxic masculinity Rosetta Stone.

For my sister, "This is How You Lose Her" was a book without any women. So many female characters, but where were the women? Where were the capital-w Women with their humanity in full sight? To her, this book was nothing more than a tired script, a re-inscription of a language that has already been inscribed too many times on every surface of our world.

Reading is a collision, shaped by the human being on the other side of the page who is looking in, and the things they bring — their wounds, their hungers — to the words on the page.

No wonder she grabbed the script out of my hand. To me, this act represents so much of growing up male in a household of women. Me, coming home with a masculine script I’d been given from the world. My sister and my mother pulling it out of my hands, commanding me: Be a good man, be different, don’t be like them. And because I love and admire them more than anything, I would try, as hard as it is to walk through life without a script.

So many people say these stories about him sound just like his books. This feels wrong to me. These stories are not his books. They are the opposite of his books. They are his books’ blank pages, the spaces between the lines. All those female fixtures, collateral damage on the path of Yunior’s self-realization, now alive, human, here to say, me too.

*

I wanted to write an essay about taking Junot Díaz out of your sky, particularly for men. I wanted to arrive in a place with a formula for how to de-heroicize the man who had been our biggest hero — not only for me but for others too. I know I’m not the only one who put him there.

There doesn’t seem to be a formula. There doesn’t seem to be a graceful way for something to fall from the sky, even a man so committed to grace in all things.

I know this: In college I am able to take new kinds of classes, on topics like Latinx Literature and Latinx Cultural Studies. I read works by Gloria Anzaldúa, Ana Castillo, Julia Alvarez, Cherríe Moraga, Yalitza Ferreras, Daisy Hernández, Patricia Engel and many others. Before college I knew two Latinx writers: Sandra Cisneros (still a God in my heart) and Junot Díaz. Two lone stars. Now, new worlds of writer and books to reach into my life, to give me companions, maps, or maybe to give me new things, too.

I know this: I had made a man into a hero, and losing him hurts. But it is better to let the sky fall. Better to let it fall and see what new things we can build. Better to deal with Junot Díaz as a human being on the ground who’s been hurt and who spread that hurt out and must take responsibility.

An old mentor from my high school years writes this to me, about Junot: It’s all deep. All pivotal. All instructive. Work through this. Internalize this. Be another type of man. So I try. Try to let the lesson in it all reach me, settle in a place deeper than my bones. Let it stay there along with the knowledge that I will be endlessly in debt to the women in my life who have chosen to take the time, energy and love to teach me, to guide me in my struggle to be different.

I look back to that cover of the book placed in my backpack all those years ago. It is a heart constructed from rainbow-colored bricks, some disfigured, glitching, others falling away. Most broken hearts are drawn with a single line. This one, run through with different kinds of brokenness, feels more accurate.

Looking at that cover, I am struck by the realization that perhaps we all deserve more than a model of what it means to be broken. So I take my eyes off the sky for a while and focus on the ground, and commit myself to living life without a script, to constructing my own map along the way, to searching for books that might one day teach me what it looks like for a man to be harmless, to be whole.

Shares