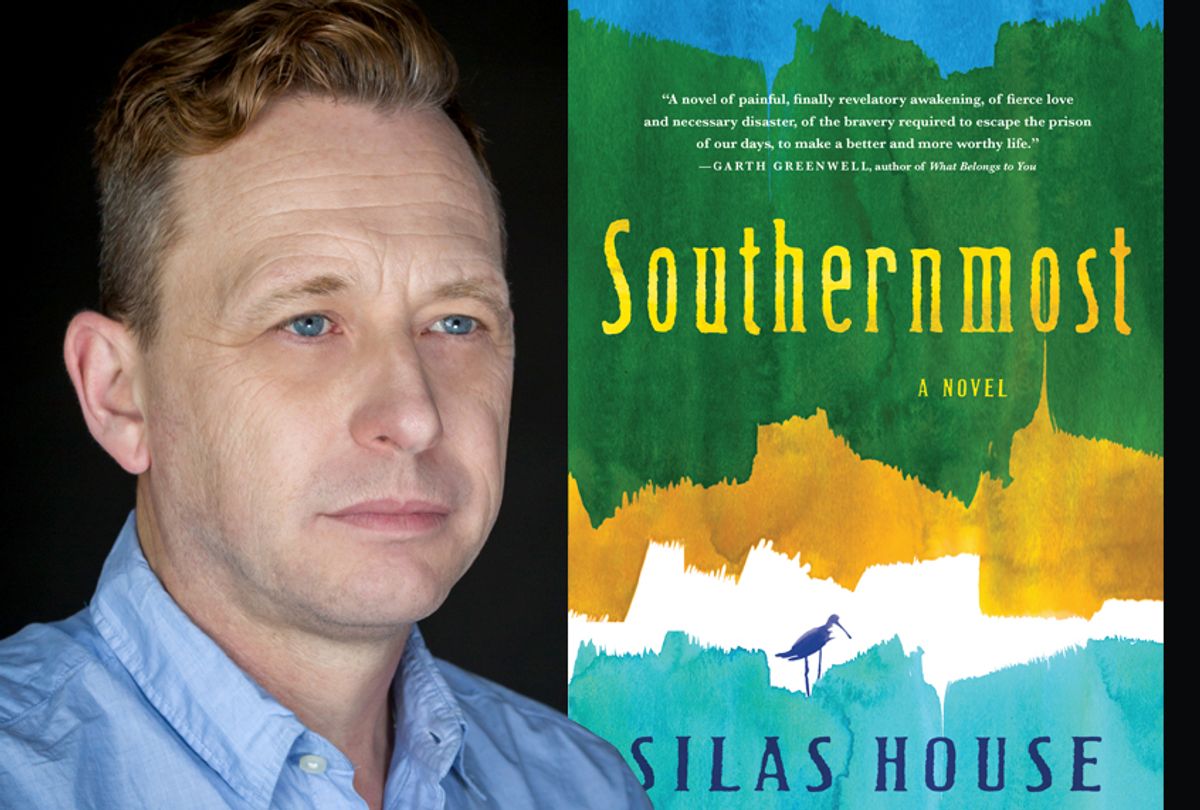

Bestselling author Silas House made his literary bones writing honestly and faithfully about the complex lives of rural Appalachians in Eastern Kentucky, where he was born and raised, with his first three novels — "Clay's Quilt," "A Parchment of Leaves" and "The Coal Tattoo." After writing two young adult novels — the most recent, 2012's "Same Sun Here," he co-wrote with Neela Vaswani — House has returned with "Southernmost," a novel for adults about a conservative rural preacher who experiences a change of heart about his religious-based homophobia, leading to a crisis of faith that upends his entire life. It's an urgent and beautifully written literary thriller about a man on the run that explores themes like the pain of atonement and the necessity of reconciliation, being published at a time when understanding across cultural and political divides seems wider than ever.

Studies show more Americans than ever support same-sex marriage, to use that now-secured constitutional right as a marker of LGBT acceptance. In 2001, the Pew Research Center showed opposition by a margin of 57 percent to 35; by 2017, only 32 percent disapproved. While it's true that once-closed minds are opening, the research shows some groups, such as white evangelical Protestants, have been slower to change. And so while marriage equality might be the law of the land, that doesn't necessarily mean an open-armed welcome for same-sex couples in all communities, or even within all families.

“Since the [2016 presidential] election, lots of people have been asking the question: How do I get along with people who have such a different notion of what it means to be a good person than I do?” House, a contributor to Salon, told me during a recent phone interview. “And I think gay people have been asking that question a long, long time. How do I continue to love somebody who thinks I’m not a good person?”

That divide came into sharp focus again yesterday, when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Masterpiece Cake Shop. Widely known as the "same-sex wedding cake case," Masterpiece Cake Shop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission still hasn't settled the constitutional matter of whether businesses can use religion as a reason to refuse service to LGBT people.

Currently, only 19 states and the District of Columbia prohibit discrimination in public accommodations based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Kentucky, where House lives — he's the National Endowment for the Humanities Chair in Appalachian Studies at Berea College, and he resides in Berea with his husband Jason Howard, also an author — isn't one of them. Neither are Tennessee or Florida, where "Southernmost" is set. I messaged House yesterday to ask if he had thoughts on the ruling.

"Americans have to decide if they want everyone to be treated equally or not," he wrote to me. "At first I thought the Masterpiece case was really complicated, with its muddying of what art is and all of that, but ultimately it's just about two people who wanted to buy a cake without being humiliated. And it's still okay for LGBTQ people to be treated that way." (He has more to say on the matter in a New York Times op-ed today.)

"Southernmost," released today by Algonquin (read an excerpt in Oxford American), is the story of Asher Sharp, a Pentecostal preacher in a rural Tennessee town near Nashville who would have sided with Masterpiece Cakeshop, believing wholeheartedly in the bakery's religious prerogative — even obligation — to refuse to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. But when a cataclysmic flood thunders through his community and a life-changing experience with a gay couple makes him reevaluate his certainty about God and his own role as a Christian and a minister, the life he'd built begins to slip away from him, and he makes a desperate decision to try to reclaim it. What follows is Asher's simultaneous spiritual awakening and downward spiral — on the road, on the run — as he attempts to figure out what a life free of the tyranny of judgment, his and others', would look like.

I spoke with House a couple of weeks ago about the risks of "Southernmost," growing up in a conservative Christian church, how the media gets rural America so wrong and why he didn't want to write "another coming out story." Here's our conversation.

Asher is your first adult male protagonist since your first novel, “Clay's Quilt,” which came out 17 years ago. You've written several memorable protagonists in the meanwhile who are women or adolescent boys. What led you to write from the adult male perspective again?

Being a father is such a huge part of my identity. I had to write about that, and also all the questions I still have about being a father, because it’s a never-ending education. [House has two children, ages 20 and 22, from his first marriage.] On one hand I do feel like I have figured some things out as a father. But it’s more about how the way being a father has shaped me and changed my point of view of the world. So much of this book is born out of the realization that as a parent you have so little power, that ultimately the great big wild world has all the power, and you’re just putting your children out there into it and hoping they’ll be OK.

I imagine that after losing a child, being separated against your will from your child would be one of a parent’s worst fears.

For me that was always my fear. Another thing is a fear of somebody not accepting my children for who they are. I want them to be accepted for who they are. I love everything about them and I want the whole world to be that way to them and it’s not.

Asher's son Justin is such a sensitive kid, he just feels the pain of the world.

I thought it was important to have a character in ["Southernmost"] who was othered, even though he’s not being othered for his race or religion or orientation, he’s othered just because he doesn’t fit in anywhere really. He’s just weird and he looks at the world totally different. And so for me that was a commentary on how to some degree most of us have felt othered in some way.

I was so struck by how the male relationships in this book are the emotional tentpoles of the story — not just Asher's bond with Justin, but also his relationship in absentia with his brother Luke, who is no longer in his life because he was rejected by the family because he's gay. I think of this book in some ways as almost a male answer to your third novel “The Coal Tattoo,” where the sisters Easter and Anneth have the driving relationship in the book. I was curious about when you decided whose point of view this story was primarily going to be told through. This is mainly Asher's story, not Luke's. Why did you make that choice?

The main thing is that I did not want to write another coming out story. But I did want to write a book about gay issues. I thought it was way more interesting to write from the point of view of a person who is struggling with the issue, a straight person who is evolving on this issue — there’s so much more trouble involved in that. And when you’re a novelist you always want as much trouble as possible.

And so to love somebody who is transitioning in that way, going from a person of great judgment and absolute confidence in what he believes to somebody who is starting to have doubts about everything that he’s been taught his whole life and he’s starting to feel like, why shouldn’t I just love my brother for who he is and not be caught up in this one little facet of him? I just thought that was more interesting, to write about somebody who was evolving, who didn’t already knew who he was.

Luke absolutely knows who he is, so there’s less trouble in his character.

The first draft was all through Justin’s point of view, but then I decided it was a book where the themes are so adult that it needed to be from an adult’s point of view. It was just too complicated in that way. And Asher’s voice just presented itself to me. I was interested in him. When you’re signing up to be with a main character for years and years, you want to go with the one that you’re most drawn to.

I think you’re absolutely correct, though. I’ve always been really intrigued by sibling relationships. In “The Coal Tattoo” I explored that through two sisters and in this book I’m looking at the relationship between brothers. I think what I love so much about sibling relationships is that if you have a sibling it’s usually your longest relationship, and sibling relationships are so complicated and interesting. And I love that no matter how different siblings are, usually that love between them overrides everything, and that’s really interesting to me, too.

Why did you not want to write another coming out story?

I didn’t have anything new to add to that, from that point of view. Mostly it was that I thought it was more interesting to come at it from the angle of the straight man, specifically a straight rural preacher, who was evolving on the issue. And mostly because to me — and I don’t mean to sound too lofty — but Asher to me is symbolic of America, and where America is right now, in that it is evolving on this issue but also has a lot of reservations. I’ve had people say to me after the Supreme Court decision [upholding same-sex marriage as a right], there’s gay marriage equality now, so the fight is over, right? It’s all done. But those people don’t move through the world every day with the gay experience, to see that we’re a long way from total equality or total acceptance.

Asher is a complex character — he's a fiercely loving and protective father who makes a very bad, very frightening decision out of that love. He's had this awakening, but at the same time he can't really wrap his head around the idea of maybe seeing his own brother in one. These aren't just self-destructive flaws, which I think are easier in a lot of ways for readers to forgive than flaws that can directly harm other people in the story. Is that a riskier choice for a novelist? Were you ever afraid that readers would maybe not embrace Asher as a protagonist?

Yes. However, I think that my main responsibility is to present a really complex character. I lived with that character for years and I just knew him inside and out and the reason why I love him is he’s really trying. He really wants to be a better person. We are always with him in his interiority and I think if we’re being honest about a character like that he would absolutely feel, even though he’s trying really hard and wants to open his heart and his mind so much, he still questions himself sometimes: Am I ready to see my brother kiss a man? Because I don’t know if I am.

I just think that’s really who Asher is, and I think that’s how most people are — they’d still have a little doubt here and there, or questions, about something like that. It is running a risk. At the same time I think it’s more important to be really complex and honest and vulnerable. What attracts me to characters is seeing their vulnerability. And if he had just been too all-accepting, it would have come off as too saint-like, and I didn’t ever want him to ever be that way. I really hate perfect people. I like conflicted, messed up people. That’s what makes Asher interesting to me.

A key theme I took from “Southernmost” is one of atonement, of seeking forgiveness. Asher experiences this sea change inside of him that leads him to want to find his brother and try to make amends. I won't spoil the resolution of the story, but you made a choice to avoid some easy outcomes there. I think a lot of times we are conditioned to forgive or absolve the uncomfortable conservative straight white men who eventually do the right thing from consequences, and I see this story saying, not so fast — even for a character a reader could came to love very much. Did you know when you were writing how you wanted to explore those themes of atonement and forgiveness?

This is not an autobiographical book. It’s all fiction. However, the only character that is me is the character of Luke. And really when it comes to page time, he’s a minor character. He doesn’t have that many scenes. He is the autobiographical element in that I have gone through what he has gone through — the coming out process, being rejected, all of that. I had to be true to the gay experience — most of the gay people I know are like, I will forgive you but I’m not going to forget this. I’m not going to forget being shunned by you for ten years while you worked your way through this.

I think a lot of people can relate to being glad that their family evolved and accepted them. But at the same time, having gone through that long period of waiting, you never totally get over that. Part of you always feels like the other shoe might drop and they might switch back.

And so I guess what I’m trying to say is forgiveness is complex, and you can have forgiveness while also not forgetting. And acknowledging that: It’s a really important moment when Luke says to [Asher], you know, it’s not that easy, you can’t just slip back in after shunning me for all those years. I love that moment. I think it’s a real moment of empowerment for anyone who has been shunned by their family or anyone they love just for being who they are.

This book is set in the here and now [the summers of 2015 and 2016]. There have been some really great novels published in the last year about people who are hiding their pasts, or who have left home and don't necessarily want to be found. Each of the books I'm thinking about was set in the mid-'90s — the last time when we could really vanish easily without the expectation that we'd be easy to locate. Asher is in the wind with a viral video at his back — you can’t get any more perilous for someone on the run. Did you always know you wanted this to be a very contemporary story?

I really did want this to be as contemporary as possible because I really wanted it to be part of the conversation of where we are right now with issues of identity and acceptance. And I had never written a book set in the digital age we’re in now. I’d never written a book set in a time period when we had cell phones. My most contemporary book up to this point was set in the year 2000, and that was borderline, right around the time people started using cell phones widely. The internet wasn’t part of your daily life the way it is now.

And then of course with this being a book about people being on the run from the law, he throws his cell phone away, but the internet is still really important in this book because of the viral video and because it allows Asher to check in occasionally on the news. So it was a challenge to write about those things. There’s just no lyrical way to write a sentence in which you use the words “email” or “internet,” you know what I mean? It’s a challenge.

Maybe that’s why so many writers now are setting their work in the ‘90s now. If we spend enough time of our day wasting time online and hating ourselves for it we can at least go back to the ’90s in the work, where people still write letters and call each other on the phone.

I get to smoke vicariously through my characters because I don’t get to in real life anymore.

This story is also rooted in a very specific small-town conservative Protestant culture, especially in that way that deep-seated beliefs about sin and damnation don't stop at the church doors. And that is not a historical relic, it's a culture that's very alive now. One of the most startling images in the book for me is the memory scene early in the story where Asher recalls his mother putting a gun up to Luke's forehead when he came out to her. What impact did an upbringing in Holiness church culture have on you as a person and as an artist?

I think it made me a writer. And it took me a long time to get over it, and what I mean by that is it took me a long time to be able to see the good in it. Because from the time I was about 16 I was just really angry at that kind of church because I saw so much racism and xenophobia and homophobia and misogyny — especially misogyny — happen in those churches.

And so it took me a long time to realize that there were positives too, and it was so complex, because there are so many good people I knew who gave me so much love who were also nodding along to those sermons that included misogyny and homophobia. I think that just helped me to think about the world in a much more complex way and see that there are almost never simple answers on humanity, and that’s the problem.

I have already had people say to me that they can’t believe this sort of mindset still exists, like with Asher’s wife in the book, who is so opposed to even being around gay people. And I can assure you there are people like that, and they exist everywhere — they’re not just in the South, and they’re not just in small evangelical churches. A lot of it is fueled by religion, but not all of it.

That’s another thing I wanted to look at in the book. People often hold the South up as being the place where that exists but I think the South is just a mirror or a microcosm for the rest of the country. The worst homophobia I have witnessed was in New York City and in Chicago, the most blatant and the most violent. However the steadiest homophobia and the subtlest has been in the small rural towns.

The consequences Asher faces for speaking out against homophobia underscores how very real a force that is in conservative rural communities, that it can even be directed at a straight man, a minister.

But in this story you also show that people aren't necessarily isolated culturally in little towns anymore. Technology makes the world smaller, for starters. I think of Cherry, the pregnant teenager who works at the grocery, who agrees with Asher and gives him support. Even small conservative towns dominated by evangelical politics aren't sheltered monoliths of fearful hate, and yet it's a power issue, right? Cherry is on his side, but she has no power in the town to throw behind him.

As a reader I feel like that is an intimate perspective of rural Southern culture that is often missing from the wider discourse. If the world is smaller than ever now, why do you think mainstream depictions of the rural South and Appalachia continue to be so miscast?

I think Americans always have to have somebody who is inferior to us, and rural people have historically been that for the media. And I think that when you get down to the psychology of it, what it’s really about is “rural” is always equated with “poor.” And in America, there’s nothing worse than a poor person, because that negates the whole mythology of the American Dream. I believe that. I think that if you went around with a microphone and asked people on the streets of America about rural people, again and again the word “poor” would come up, and also the word “ignorant.”

And at the same time, a lot of romantic notions would come up. People would say that rural people are all churchgoing and that they don’t lock their doors at night, all that kind of romantic stuff. Anything that romanticizes people or vilifies them, what you’re doing is simplifying them. And I think that’s the purpose that rural people have served in American culture ever since media began in America.

Any time you want to present someone as stupid, you assign the word “hillbilly” to them, no matter where they’re from. For instance, when Sarah Palin was in the news, and people would refer to her as the Wasilla Hillbilly. Well, she’s from Alaska, which is the farthest place from hillbilly country you can think of, since that's associated with Appalachia. I think it’s something that has become so immersed in our national consciousness that I think it’s transcended what it began as in the first place. I don’t know if that will ever be conquered.

Shares