George Lucas's "Star Wars" film universe and the associated toys, comic books, TV shows, video games and other ancillary products have earned billions of dollars since his original film debuted in 1977. But "Star Wars" is more than a commercial juggernaut which helped to create the very idea of the "Summer blockbuster." For many people around the world it is generation-defining film that influenced their lives in ways both small and large.

"Star Wars" is also an example of what literary scholars, anthropologists and others have described as the "monomyth" (or "the hero's journey"), a set of omnipresent storytelling conventions and archetypes in (Western) storytelling. In many ways, the monomyth is an extension of the collective subconscious and how human beings try to make sense of the world around them and the particular challenges that come with being sentient and aware of their own mortality.

But "Star Wars" is also much more than the monomyth. It is also a deeply political text. To explore that aspect of "Star Wars" I recently spoke with Max Brooks who is the author of the bestselling zombie epic "World War Z" and also the new book "Strategy Strikes Back: How Star Wars Explains Modern Military Conflict."

In this conversation Brooks shares some of the lessons that "Star Wars" can teach about democracy and government in this moment when right-wing forces are ascendant, the role of the military in society, diplomacy and statecraft, military strategy, as well as the relationship between the common good, freedom, and security.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Is the United States the Galactic Empire or the Rebel Alliance?

Neither. We’re the Republic. We have been far too complacent for far too long. We are accidentally sowing the seeds of our own demise.

We saw this during the Prequels, the anger at a senatorial system and the parliamentary process, how is that any different than what we see all around the world? Where we see generation and generation of people who have grown up with democracy and take it for granted? Obama said after Brexit that “We’ve got generations who've grown up and never known democracy under threat. They take their civil liberties for granted.”

By the way, we all love to hate on Jar Jar. But Jar Jar represents the well-meaning public that accidentally votes for a dictator. Everything that’s happening today, and not just in America, but you see democracy under threat in so many different ways.

What can the rise and fall of the Jedi in "Star Wars" teach us about this current social and political moment in America?

Primarily that the idea that you are born with the Force--or not--gets to the notion of birthright.

The problem with birthright is that it lets the rest of us off the hook. You see that in the volunteer army with blow-off platitudes such as, “Thank you for your service,” which could be translated as “Better you than me,” “You chose this, go away,” There’s a million reasons for it, but "thank you for your service,” is the worst thing that’s ever happened to our national defense. It used to be we were all in. I don’t mean the draft, I mean war bonds, rationing, war taxes, the notion that we’re all in this together. But now there is a specialized volunteer force that goes and does the dirty work while the rest of us catch up on Netflix.

That attitude in one form or another is how the whole country feels, maybe not to that level of hostility, but there is this notion of, “Hey, you chose this task. I don’t have to feel bad for you. You’re not a draftee. You weren’t ripped out of your parent’s arms.” Trump basically said that about the green beret who was killed in Niger. Trump didn’t mean it in a bad way. He just meant is just a statement of fact. Hey, he knew what he’s getting into.

Mercenaries and the privatization of war are now a firm feature of how America and other countries--and huge corporations--wage war and use violence to advance their goals. The outsourcing of war is also present in "Star Wars".

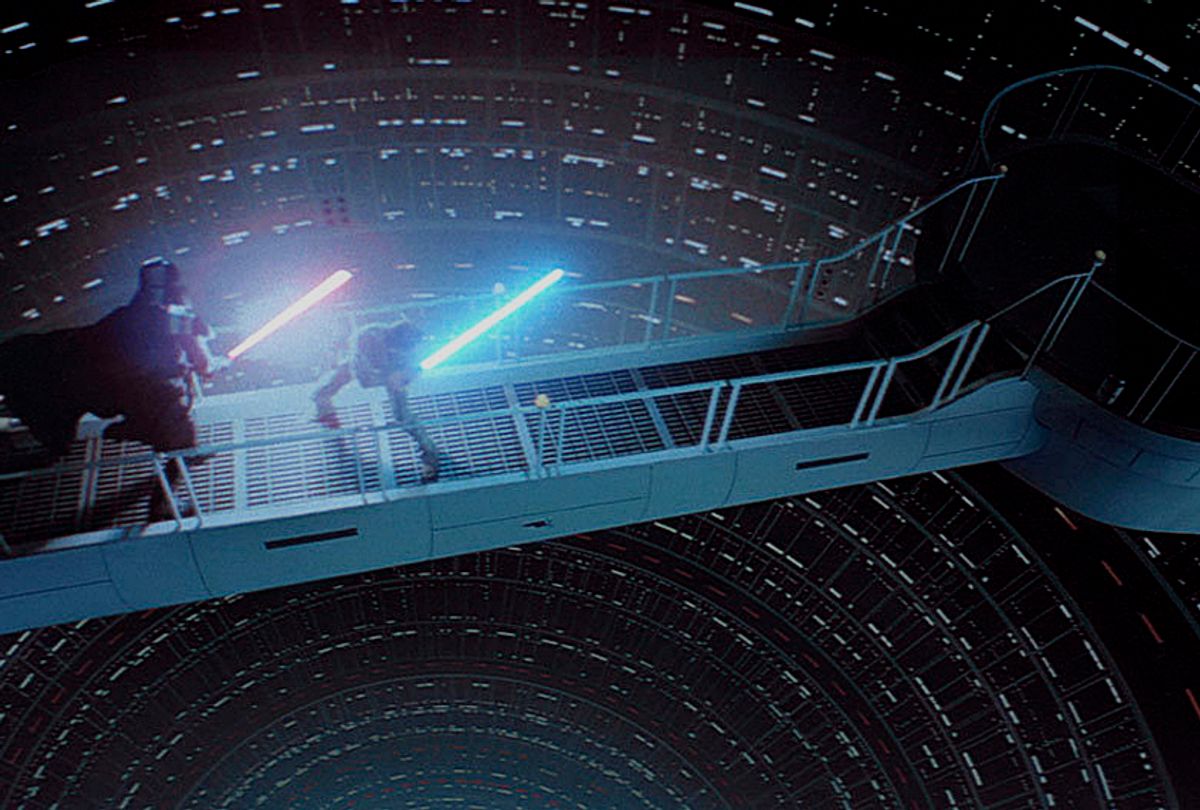

You see it in “Empire Strikes Back.” Because the regular military is very suspicious of private contractors and there is literally a line in "Empire Strikes Back" when Admiral Piett says, “Bounty Hunters, we don’t need that scum".

But bounty hunters could go places other people could not. They also could do things others wouldn't or couldn't, the rules didn't apply. Even the Empire had a way of fighting that bounty hunters do not.

With your new book "Strategy Strikes Back: How Star Wars Explains Modern Military Conflict," how did you balance getting the amazingly rich and fictional universe of "Star Wars" correct while also teaching lessons about government and the military in the "real world"?

We tried to strike a balance between civilian and military writers. It was a very ambitious project. First we were trying to teach people in the military about strategy because the cadets at West Point, The Army War College, Annapolis, Naval War College, Air Force Academy, and the like are very busy.

“Star Wars” is a great way to touch on a range of issues and a higher level of strategic thinking. There was a military element, but then there’s also a civilian element. We also wanted the book to be accessible to the general public. These are insulated voters who will then vote for people who don’t know anything about military strategy, who will then in turn make decisions that are horrific and get a lot of people killed. Educating people about strategy isn’t just an intellectual pursuit. In a democracy it is a civic duty.

If you were going to crystallize the lessons that "Star Wars" teaches about politics and government down to three or four points what would they be?

“Star Wars” --particularly the prequels--teaches us that that democracy is not a spectator sport. Democracy--especially a republic--may be inefficient and frustrating but it is specifically designed that way as a means of stopping dictators. Better to have a squabbling Imperial or Republican Senate than an emperor who dissolves the Imperial Senate.

I think that’s one thing. Another is while dictatorship might seem efficient on the outside, they’re also infinitely vulnerable. Because by nature, when you have a dictatorship, you have singularity of thought. You literally have Vader choking someone at the staff meeting who disagrees with him. That means you can get a lot of stuff done a lot quicker than in a republic. But that one guy who might have raised his hand during a staff meeting and said, “Hey. There’s a hole in the Death Star,” he’s never going to speak up.

Democracies are infinitely more resilient because you can’t kill an idea. Once Palpatine was killed that was the end of the Galactic Empire. He was the Empire because everybody was serving Palpatine. Everybody was fighting for Palpatine. Everybody was afraid of Palpatine. The moment he’s gone, there’s nothing left. It all crumbles, as opposed to a republic which is based on a set of principles that we all choose to live under.

You have also had great success working on comic books and graphic novels and of course the novel "World War Z" which was loosely adapted into a profitable film starring Brad Pitt. How did this all happen? Random accident? Strategic planning?

I keep going and I’m always trying to be conscious of the creative minefield. You don’t want to ever start trying to anticipate what the audience will want. I mean other people can do that and good for them. But for me that would be the death of me if I ever started to think, “Well, I was successful with this book, so I should write a sequel because that’s what people want.”

Literally, the only time I’ve ever even considered it is with my "Minecraft" book. That’s only because I have little kids, eight-year-olds and nine-year-old saying, “I’ve never read a book before and this is my first book.” Yes, that is cool. Then parents, because I’m a parent. I really had a rough time in school. To have parents come up to me and say, “This is the first time my kid has voluntarily picked up a book,” or “This is the first time my child has chosen a book over a videogame.” That’s pretty damn hard to walk away from.

What was the pressure like to do a sequel to the "World War Z" novel?

My agent Victor, god bless his soul, recently passed away. To his dying day, he thought I was insane. He would say, “It’s right there. You’ve hit. You can hit again. Why aren’t you doing this?” I can only speak honestly. If I suddenly wake up tomorrow and I think, “Oh, my God, I have it!" I’ll totally write another one. But I’ll say, honestly, I think I’m probably the world’s worst businessman.

Why do you think “World War Z” was so successful? I remember buying it a Borders bookstore and reading it over a weekend without stopping. Then I had to go buy both versions of the amazing audio book.

I don’t know. And I don’t even want to know because I write from a very personal place. I write for me. Every time I try to not write for me, every time I tried to write for an audience or think about what’s popular, it never works out for me.

If I was that guy who could anticipate trends and excitement in the public, I’d be a screenwriter not a novelist. I’m still that weird 12-year-old kid in the back of the room thinking about stuff that the other kids weren’t thinking about. It took me a while to get there, but that’s all I can be. That’s all I’m good at. Why waste anybody else’s time not being myself?

Some people can fake it for decades and keep cashing those checks and making uninspired stuff because the people love it.

I say "good for them." I’m in no position to judge anybody. I also write for me because that’s the only way I know to prevent failure because I’m as sensitive as any other writer. It kills me to have to put stuff out there and have somebody not like it. The only way I know to not see my work as a failure is to know that I like it first. That’s it. I mean that’s the only way because if I don’t like it, but I think the public is going to like it and the public doesn’t like it, that means nobody likes it, that means I failed. The only way to put something out there and know in my heart, “OK, if they don’t like it, at least I do.”

How did you manage how so very different the "World War Z" movie was from your original material? As an almost lifelong fan of Romero's genius zombie films and what you accomplished with "World War Z," your book was so much better than the movie.

I had to make my peace with it because I also lost my way a little bit, especially when I saw the trailer and it wasn’t me. The guy who got me back on track was [writer] Frank Darabont because you need those people in your life who can give you perspective.

My wife also gave me perspective. She said, “You need to call Frank because nobody has been screwed over more than him with what happened with the 'The Walking Dead' TV show".

Frank took this obscure comic book that we as nerds liked, but the general public had no idea existed. He had to fight tooth and nail to get this show made, because as we know now, AMC did not want it. Finally when it got out there they rewarded Frank by firing him.

I e-mailed Frank about the movie and said, “You know, Frank, with all this going on people say that it’s going to ruin my book". He is like, "How can it ruin your book? Your book is written. What are they going to do, go back and edit your book? You have your side of the story. Why are you worried about what’s going to be on the screen? You don’t have anything to do with that. You worry about your book.”

Then god bless him, he passed my e-mail along to a friend of his, who then wrote me and said, “Frank, listen, tell your friend, I like 'World War Z'. It’s a good book, but also tell him that it doesn’t matter what happens in the movie, because the whole reason I’m assuming that he sold the movie rights in the first place was to promote the book. That’s why any writer does that. As a result of this movie, no matter what’s on the screen, more people are going to read his book. Isn’t that the whole point? Signed, All the best, Stephen King."

That got me back to who I was at the beginning of the whole film process. I have to say I feel like I got very lucky that the movie completely ignored my book because I didn’t have to watch my characters being manipulated. I never watched my story get eviscerated. I literally didn’t have to watch any of my book on the screen doing what it wasn’t supposed to do.

It wasn’t my story. It wasn’t my character. I didn’t invent Gerry Lane as far as I’m concerned. He can do whatever he wants. Ultimately, once I got passed the opening credits, I watched a movie that had nothing to do with my book other than the title and it was a tremendous relief.

Coming full circle, why do we love “Star Wars” so much?

We love “Star Wars” because it touches all the basic tenets of what it means to be a human being. It really is universal. It is good versus evil. It is a coming of age story. It is morality. It is love. It is hate. It is everything that we see in ourselves and that’s why George Lucas could tell his story in such a fantastical setting.

Shares