“The travail of freedom and justice is not easy, but nothing serious and important in life is easy. The history of humanity has been a continuing struggle against temptation and tyranny—and very little worthwhile has ever been achieved without pain.” — Robert Francis Kennedy

“There is no normal life that is free of pain. It's the very wrestling with our problems that can be the impetus for our growth.” — Fred McFeely Rogers

June 6, 1968: Robert F. Kennedy is shot to the ground in Los Angeles’s Ambassador Hotel, triggering one of the most dramatic waves of collective mourning the nation has ever seen. “I left the next morning, and I cried all the way from LA to Atlanta,” recounts Congressman John Lewis, starting to choke on his words during interview. “I kept saying to myself, ‘What is happening in America?’ To lose Martin Luther King, Jr., and two months later, to lose . . .”

Witnessing the former freedom fighter and current septuagenarian break down before the camera delivers a shock to the system. Could the assassination of any white man today spur this type of sorrow?

February 16, 1968: Another unlikely icon makes his national debut with an educational kid’s show that will eventually break the record for longest-running children's television series. A man who was once tagged “Fat Freddy” by his peers will stand before the next generation with a lesson of tolerance and forgiveness, inviting all to “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

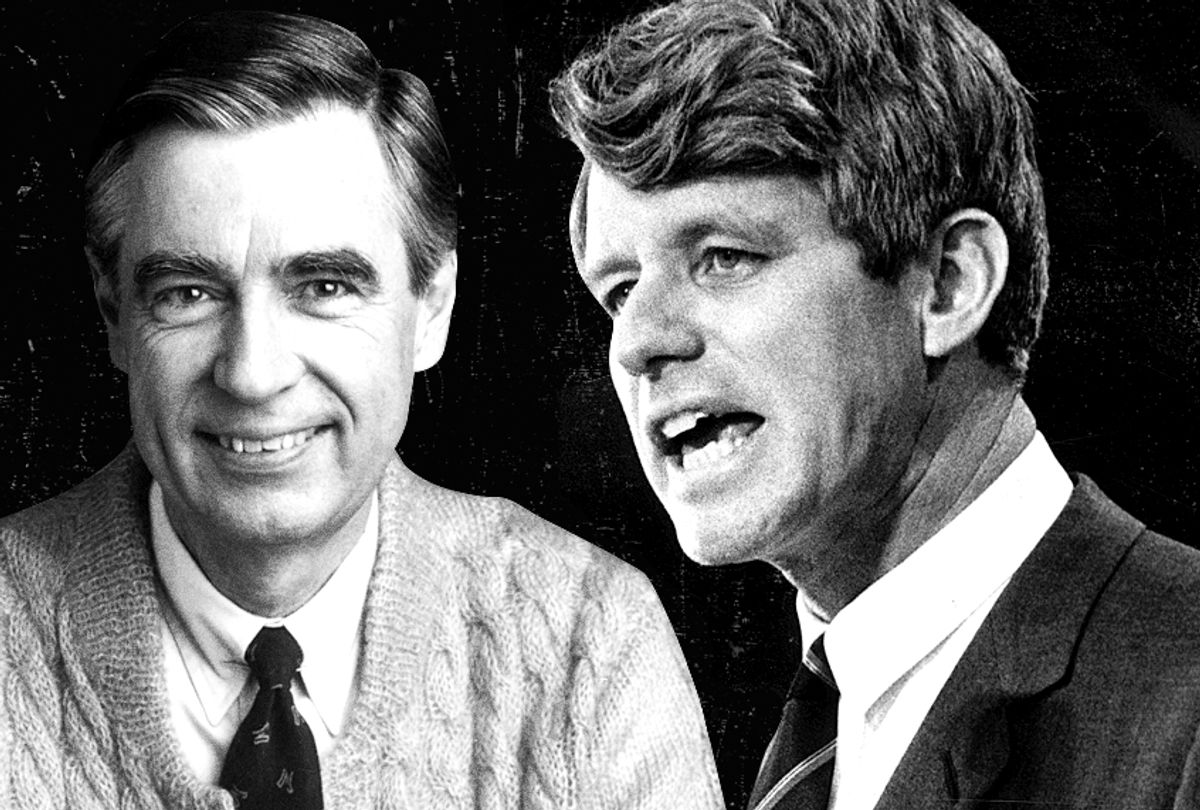

Aside from a rather anagrammatic aspect to their full names, the two men couldn’t seem more different: one a life-long Republican and ordained Presbyterian minister, the other a Catholic lawyer and Democratic royalty; one six feet tall, the other the “runt” of the family; one naturally athletic, and the other so gangly that his 1985 breakdancing is painful to watch to this day. But two new documentaries, released within months of each other, reveal just how much Kennedy and Rogers share in common: Dawn Porter’s “Bobby Kennedy for President”, on Netflix since April, and Morgan Neville’s “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?”, in theatres June, two days after the fiftieth anniversary of RFK’s assassination.

Porter’s four-part series follows Bobby’s transformation from hotheaded Attorney General to civil rights activist and presidential contender, and Neville (who nabbed an Oscar for “Twenty Feet from Stardom”) chronicles Rogers’s influence on both public television and the ethos of children’s entertainment. Born three years apart — and both into affluence, though of varying degrees —the two men were rife in contradiction, yet consistently on the side of the disenfranchised. Just as it’s hard to imagine that the “most trusted white man in Black America” would have holidayed regularly in Europe as a child, it is equally difficult to imagine any wealthy white guy, let alone a conservative minister, devoting his life to making children’s television a radically progressive space.

What both docs continually demonstrate is how Kennedy and Rogers exploited their white male privilege before the phrase even existed, publicly bringing those without such power into the folds of mainstream America. Watch Bobby break bread with a hunger-striking Cesar Chavez and march with Dolores Huerta for farmworkers rights; see Fred cool his feet in a kiddie pool with his Black neighbor, Officer Clemmons, at a time when Jim Crow still poisoned parts of the South. On some level it may seem glib to compare these actions, so different are they in scale, but on a base symbolic level, they were saying the same thing: “I’m no better than the brown or black man, and neither are any of you who look like me.”

Surprisingly, it is Kennedy, not Rogers, whose charisma grew more slowly. Porter’s opening credits present Bobby in cool “Mad Men”-esque silhouette — the opposite, perhaps, of his initial public persona, as we come to learn from his Constituent Case Aid William Arnone, a frequent talking head on the film.

“He was small, he was gray-skinned, his handshake was limp,” Arnone says of meeting the politician when he was running for Senate. “I thought, ‘Oh my God, he’s nothing like his brother….”

Bobby’s oratory skills were also, apparently, underwhelming. “He was terrible — he was high-pitched, he was stuttering. I thought, ‘He will never amount to anything, ever ever ever.” So too one may have thought of a preacher with a penchant for puppets.

When others would — and have — rested on their laurels, Fred and Bobby nudged the barometer toward the cause of the underdog, whether that be the quadriplegic boy in a wheelchair singing “It’s You I Like” on Mister Rogers’ porch, or the babies with bloated bellies whom Kennedy visited during his 1967 tour of the Mississippi Delta.

“Considering we have a gross national product of some 700 billion dollars, and we spend 75 billion dollars on armaments, you’d think we would be doing more for our poor,” Kennedy reflected at the end of his trip, “particularly for our children, who had nothing to do with being born into this world.”

With today’s GNP over 14 trillion, and extreme poverty worsening under our current administration, one has to wonder what would have happened had Kennedy survived. Would “bleeding heart” epithets ever gain traction if it remained manly to have a heart in the first place? Rogers and Kennedy made empathy central to their credos, yet as both documentaries make perfectly clear, there was nothing wishy-washy about them.

“Land of Make Believe” or not, Rogers was a realist who made the exigencies of his day the bedrock of his series. Kennedy’s death itself a catalyst for the show.

“What does assassination mean?” asks Daniel Tiger within days of the event.

“Well, it means someone getting killed in a sort of surprise way,” answers Betty slowly.

“That’s what happened, you know!” says the puppet. “That man killed that other man!”

No matter how hokey or naïve Rogers may come across onscreen, the man was intensely invested in how the harshness of life affected children. Similarly, Kennedy— father to eleven (!) of his own— was arguably at his best in their presence.

“He was very curious, he didn’t talk a whole lot,” says Marian Wright Edelman, Director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund at the time of the Mississippi visit, “but he would ask a lot of questions. I was very moved by how he related to children, the ways in which he could express emotions through touch.”

In other circumstances, watching barefoot children swarm the politician could feel like yet another white-man-savior ploy for a vapid photo opp. Instead, Kennedy looks quietly shaken, doesn’t smile the camera—doesn’t smile broadly at anyone.

Also an avid listener, Rogers’ lingering pauses with his guests could leave them a bit confused, as cellist Yo-Yo Ma reminisces in the film. And, like Kennedy — whom Arnone described as having “the saddest face I’d ever seen in my life,” the television host grappled with depression and loneliness — growing up a sickly only child until the age of twelve, and privately questioning his impact as an adult in time of media cynicism.

Neither doc is flawless — both tend to gloss over the less savory aspects of their late heroes, like Kennedy’s initial enthusiasm for the McCarthy hearings or Rogers’s obsession with weighing 143 pounds (which, even today, is used as fundraising fodder when it verges close to eating disorder terrain). Still, by the end of the films the humanity and complexity of each man is thrown into stark relief. Several have claimed that Rogers “was too good for us,” and perhaps the same could be said of Kennedy. But that kind of thinking lets us all off the hook.

“Every generation inherits a world it never made,” said Bobby, “and, as it does so, it automatically becomes the trustee of that world for those who come after. In due course, each generation makes its own accounting to its children.”

Painful and impossible as it may seem, it is time to do just that.

Shares