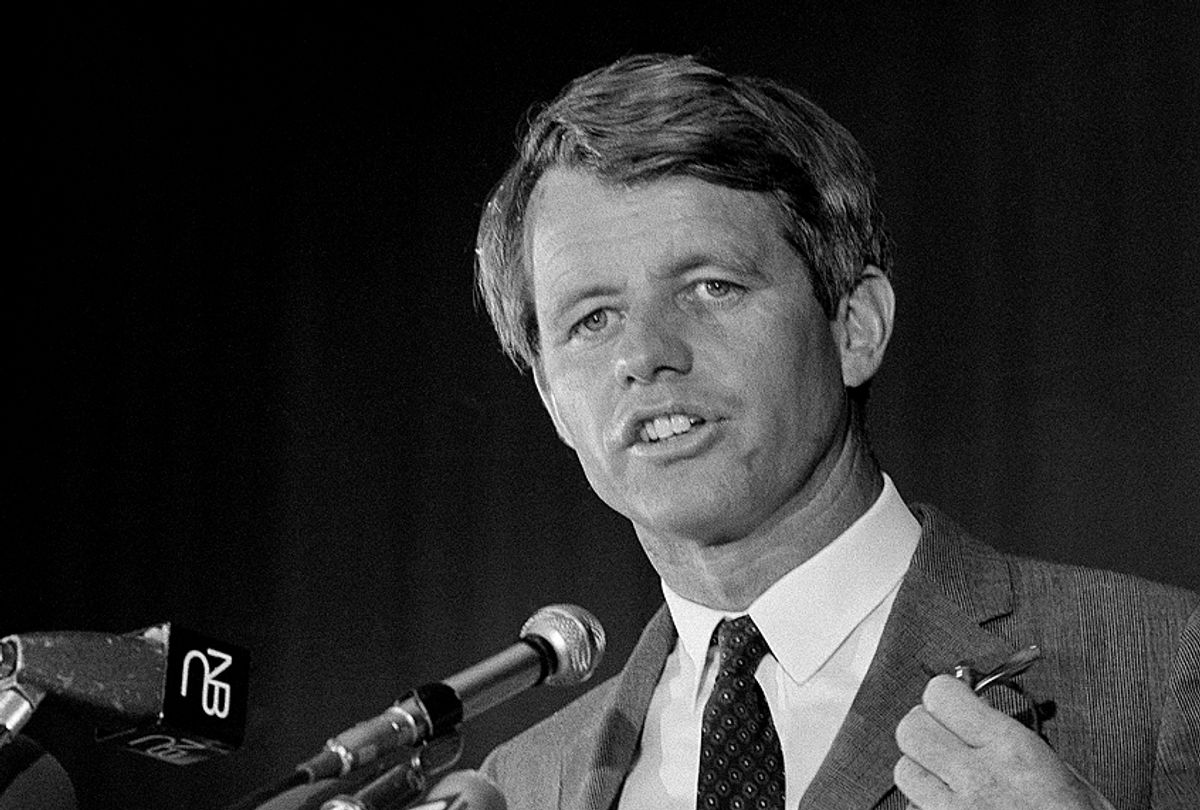

On June 7, 1968, two days after Robert Francis Kennedy had been fatally wounded in the pantry of the Ambassador Hotel, The New York Times ran a front-page story under the headline WOMAN SOUGHT IN KENNEDY DEATH.

“The Los Angeles Police Department pressed a statewide search today for a possible accomplice in the assassination,” the article began. One witness had described seeing this woman running from the scene of the crime shouting, “We shot him! We shot him! We shot Kennedy!” Another said that, minutes before the attack, he’d noticed someone “of similar description” accompanying a young man whose appearance, in his opinion, resembled Sirhan Bishara Sirhan, the gunman currently in police custody: a 24-year-old Pasadena resident of Palestinian descent who’d been disarmed and apprehended at the scene.

Police had issued a statewide bulletin for “a Caucasian female, between 23 and 27 years old, five feet six inches tall, who had been observed at the assassination wearing a white voile dress with black polka dots and a bouffant coiffure.”

On the night in question — Tuesday, June 4, 1968, the all-important California primary — more than a few of the young campaign workers who’d packed the hotel’s sweltering ballroom would have resembled, at least in a general fashion, the alleged co-conspirator. However, no one fitting this description would ever be found. Still, during the tragedy’s first days, the possibility of her existence, which contradicted the most likely explanation — Sirhan was the sole perpetrator — had taken hold.

That evening, Kennedy delivered a brief victory speech to his crowd of jubilant staffers. Afterward he ducked into a narrow pantry. It was just after midnight. He was about 10 yards from the corridor’s exit when, from the clutter along the wall, Sirhan — hiding between an ice machine and stacking tray, a .22 caliber pistol in his hands — jumped out and opened fire. There were perhaps 30 people in the vicinity. Kennedy was hit just below his right ear, the bullet piercing his skull. Five others were also struck. In the chaos that ensued, multiple people rushed the gunman, pinned him to a steam table, where they struggled, desperately, to get the revolver out of his clenched hand. All the while Kennedy, the target of the attack, lay bleeding to death on the cold concrete floor only a few feet away.

No video exists of the assault and its aftermath, parts of which were captured in audio recordings and photographs. Afterward, the multiple eyewitness accounts would vary wildly regarding the number of shots fired, the candidate’s position at the instant of the attack and Sirhan’s demeanor as he emerged from the shadows at the wall. Taken together, the surviving testimony, in its contradictions, speaks hauntingly of the confusion the violence incited: a roaring, riotous tumult that everyone present seemed to experience differently. Even the most basic details were contended. Afterward, two of the men who’d helped subdue Sirhan, ex-NFL tackle Rosey Grier and the Olympic decathlete Rafer Johnson, would each claim, in all honesty, to have been the person who finally tore the gun out of the assassin’s hand.

This much we can say for sure: Sirhan Bishara Sirhan, a deeply delusional young man, had staked out the hotel in advance, practiced his marksmanship at a nearby shooting range and, surging across the pantry’s narrow corridor, had emptied the bullets in his Iver Johnson Cadet Revolver at Robert Kennedy, at which point he was immobilized against a steam table and held there until the police finally arrived to take him away.

Recently, in the run-up to the 50th anniversary of the assassination, the idea of a larger, hidden plot remains as prominent as ever. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., 14 years old at the time of his father’s murder, told The Washington Post that he now believes someone else was present in the pantry that night — that Sirhan Sirhan has been wrongly convicted of firing the fatal bullet. A new four-part Netflix series, “Bobby Kennedy for President,” directed by Dawn Porter, spends much of its final episode documenting the efforts of 92-year-old Paul Schrade, a labor advocate and important volunteer for Kennedy’s 1968 campaign — he was one of the five bystanders also shot that night — who for decades has been lobbying for a new investigation into the existence of a second gunman.

To be sure, throughout the 1960s, both federal and local law enforcement agencies — from the FBI’s terrifying COINTELPRO campaign to the Los Angeles Police Department’s Special Operations for Conspiracy unit (this was its actual title) — repeatedly conspired to infiltrate and disrupt civil rights organizations and political movements.

What’s more, in the days that followed Robert Kennedy’s murder, the investigation was handled poorly. The LAPD searched Sirhan’s residence without obtaining a warrant, claiming they’d been allowed to do so by family members. Afterward, Sam Yorty, the mayor of LA, revealed in an interview with Radio News International that they’d recovered incriminating notebooks at the house — “they’re not very clear,” he said, “but there’s a direct reference to the necessity to assassinate Senator Kennedy before June 5, 1968” — which amounted to an unbelievably reckless statement; a defense team could now argue against the inclusion of such evidence at a future trial on the grounds that Yorty had prejudiced future jurors.

It didn’t stop there. In the days that followed, Mayor Yorty and Police Chief Thomas Reddin went so far as to propose a conspiracy theory of their own: Sirhan had acted, they said, in the service of outside Communist agents, who were hellbent on undermining the American government. Yorty explained that the notebooks he’d seen, which he’d admitted were barely legible, “clearly expressed Communist sympathy.” He even claimed that the suspect had attended “meetings where Communist organizations or Communist front organizations were in session.” The same day, Reddin backed him up by mentioning a “subversive file” that the department had been keeping on Sirhan’s secret activities. Together they tried to convince the public of a wider, sinister, possibly international plot — perpetrated, in the manner that LA law enforcement had been warning about for years, from the fringes of the American left.

But then, that’s the thing about conspiracies, both in theory and in practice: they almost always benefit the individuals and institutions in our society that already control an outsized amount of power. As theories, they can be used to obfuscate and confuse, a means of false equivocation. And, as real-world plots, they allow coordination among those at the highest echelons of power to undermine and eradicate actual and perceived opponents. After all, a real conspiracy is at its heart a luxury: a matter of tangible resources (committing and then covering up an honest-to-God wide-ranging corruption plot is never cheap). It’s a tactic that, when weaponized, is especially effective against those with the least access to power: the marginalized, overlooked and silenced segments of American society.

These were the people who institutions like the FBI and LAPD repeatedly plotted to silence. They were also the individuals who, during his brief breathtaking campaign for president in the spring of 1968, Robert Kennedy had somehow managed to gather together into what would go on to become one of the greatest electoral coalitions in American history.

The “have-nots”: This was how Kennedy referred to his unique constituency. “A new political coalition,” the journalist Jules Witcover called it: “the poor and the minority groups alienated from the affluent; young issue-oriented America turned off by the inability to reach their elders and by loss of faith in them; the great middle class alienated by a war that was sapping its newly acquired affluence from its sense of moral justice.” He was right. Nothing like it had ever existed in American politics. But then, there’d never before been a candidate quite like Bobby Kennedy, someone who, in both actions and his idealism, embodied a sentiment of justice, reconciliation and compassion that crossed the usual divides of race and class.

“Our country is in danger,” he said that spring. “Not just from foreign enemies; but above all from our misguided policies — and what they can do to the nation that Thomas Jefferson once said was the last, best hope of man.” He was talking about the war in Vietnam and the lack of support to ending poverty and discrimination at home. “This is a contest on, not for the rule of America, but for the heart of America.”

Things were only going to get better if people were willing to set aside their expectations and embrace perspectives and experiences outside their own. “The failure of national purpose,” he said, “is not simply the result of bad policies and lack of skill. It flows from the fact that for almost the first time the national leadership is calling upon the darker impulses of the American spirit — not, perhaps, deliberately, but through its action and the example it sets — an example where integrity, truth, honor and all the rest seem like words to fill out speeches rather than guiding beliefs.”

He tried to lead by example. As a senator he’d directed, in a practical initiative to lessen the suffering of his poorest constituents, the development of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn. With Cesar Chavez he picketed grape-growers, demanding better wages and living conditions for workers. He challenged white college students to do more than protest; how could they give back to the communities whose members hadn’t been privileged enough to receive multiple draft deferments? “You’re the most exclusive minority in the world,” he said to them. “Are you just going to sit on your duffs and do nothing, or just carry signs and protest?” At the center of his sense of justice was a burning authenticity: a desire to see himself as clearly as he struggled to see the world around him.

That April, while he was campaigning in Indiana, he learned that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated in Memphis. The speech he delivered that night — extemporaneously, to a mostly African-American crowd that hadn’t yet learned the news — would be credited with helping Indianapolis avoid the violent riots that engulfed other parts of the country. A day later, at the City Club of Cleveland, he told the audience:

The question is whether we can find in our own midst and in our own hearts that leadership of human purpose that will recognize the terrible truths of our existence. We must admit the vanity of our false distinctions among men and learn to find our own advancement in the search for the advancement of all. We must admit in ourselves that our own children’s future cannot be built on the misfortune of others. We must recognize that this short life can neither be ennobled or enriched by hatred or revenge. Our lives on this planet are too short . . .

Conspiracy theories will never be about the future. They’ll always be about the past, its unraveling threads, an act of looking backward that occludes a more compassionate perspective on the present — on the hard, everyday effort that improvement demands. I don’t mean to diminish the debate over the circumstances of the violent, terrifying attack Robert Kennedy endured in the narrow pantry corridor of the Ambassador Hotel. The point is that the corridor itself will always be endless; the longer we dwell there the less answers we’ll find — losing, instead, any chance we might’ve had to retrace the shape of a world he worked so diligently, in his deeds and message, to articulate.

If on the fiftieth anniversary of his death we’re going to talk about second gunmen and the number of shots fired and possible accomplices in polka-dot dresses, then we should at least also take the time to reiterate that it’s always the most marginalized members of his striking coalition who tend to suffer the most from conspiracies, real and imagined. That’s how power works. And to try and find in that concrete-cold rabbit hole of his death anything besides horror and loss is to set yourself up for an act of negation — the opposite of the self-awareness that Kennedy so vibrantly expressed.

In retrospect, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Rosey Grier and Rafer Johnson, who together had struggled to subdue Sirhan, would remain adamant, for decades afterward, in their contradictory versions of the incident.

At one point, Grier even went so far as to call Johnson to try and get to the bottom of it.

Johnson just reiterated that’d he’d been the one to disarm the assassin.

“Why would you say that?” Grier asked.

“Well,” Johnson explained, “that’s the way I recall it.”

Grier was incredulous: “How can you recall something that didn’t happen?”

Shares