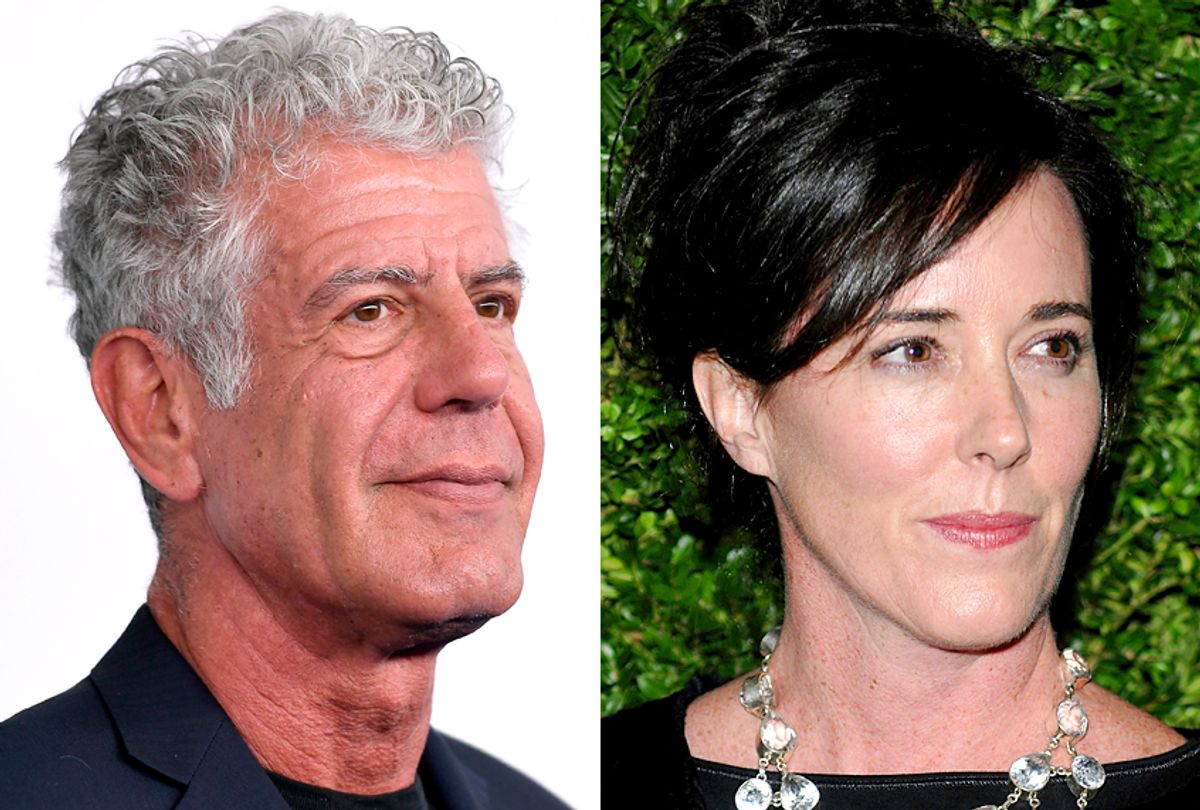

I am so sorry for your loss. I am so sorry that the life of this person you cared deeply about ended in such a shocking and cruel way. I am so sorry about your own ideations and attempts. And I'm so sorry that this profoundly tragic week has opened up your wounds. I am sorry that the suicides of two brilliant, creative, joy inducing individuals — Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain — have been both a gutting public loss and a profound reminder of private loss. They have for me too.

My friend Alli was smart, difficult and funny. She taught me a lot in the fifteen years we knew each other. She taught me about film theory and long wearing lipstick and she failed to teach me a few guitar chords. She taught me about treatment resistant depression too. And she was the one who first taught me that everything I'd previously been privileged to not know about suicide was wrong. Because she tried harder than anybody I've ever know to not die.

She saw her psychiatrist regularly. She tried an endless variety of prescription antidepressants, hoping to find the right cocktail to adjust her brain chemistry. She checked herself in to hospitals, repeatedly. All the while, she came around and played with my kids when they were little, sniffing in their sweet scents and letting them curl their fingers in hers. And when she felt she couldn't leave the house, she'd have me over to just sit on the floor with her and pet her dog and talk, as she methodically cycled through the rituals her OCD demanded of her. It was a brilliant summer morning when her mother called me to tell me the news.

Charlie was a crank and a blowhard and the most generous, loyal soul you could imagine. His misanthropic exterior concealed a heart of pure mush. You saw it when he talked about his daughters. He argued with me constantly about politics and he took me out for french fries when I had cancer. He stuck around when some of my most trusted friends bailed, because that was his nature.

I was walking in to a give a presentation when I got the text. It had almost certainly been an accident, but the depression and anxiety, exacerbated by his long term health issues, had been overwhelming him lately. As much as you can ever know anything about another person, I know that he didn't want to die. I know he wanted to get better and be a great dad.

In the darkest moments of my own anxiety and PTSD, I've never wanted to die. But I have learned a great deal from that experience about what it's like to feel like you have no idea how you're supposed to go on living. To find yourself, terrifyingly, without a road map forward.

This week, a Bay Area friend who has had lifelong depression talked about how she was chided for discussing Kate Spade's death on the same day as the important California primaries. A bottom feeding gossip columnist heavily implied that Spade's husband was to blame, while posting explicit conjecture about her method of death. Well-meaning pundits have speculated about how wealth and success are no insurance against self-harm. (To which I say, well, duh.) They've also frequently been offering advice and resources for "reaching out" if you're struggling. That last one is at least all well and good, but the burden of acknowledging and addressing mental health issues shouldn't fall exclusively to the person who is suffering. And it omits that those who live in the aftershocks of suicide and its attempts also struggle and suffer.

As the NHS points out, one of the many ways you can get PTSD and PTS is "an unexpected severe injury or death of a close family member or friend." Similarly, research shows that roughly half of people who've attempted suicide experience PTSD symptoms afterward.

What does that mean? It means symptoms like anxiety, sleep disruption, difficulty concentrating and hyper vigilance. It also can mean that certain sounds and smells and yes, news stories, can prompt not just the memory of the traumatic event but a physical and mental response. The body re-experiences the event. The pulse races. The breath becomes short. And disturbing images appear, uninvited and definitely unwelcome. Exposure and cognitive behavioral therapies can dramatically minimize the effects. Graphic news stories, rampant speculation, and shaming and blaming will not.

It's easy to decry the overuse of the word "triggered" — the last time I talked to Charlie, in fact, he was making fun of me for using it in a story — but trauma is real and it works on the mind and body in quantifiable ways. I don't make the rules here. Brain chemistry, alas, does. If you have grieved for someone who died by suicide, if you have contemplated or attempted suicide, these are extraordinarily difficult days. And if you are fortunate to have not had those experiences, please be sensitive to those who have. Please educate yourself about mental health issues, so you can talk abut them with compassion and empathy and a clearer understanding of how they work.

I miss my friends. I know you miss yours. I know you think about them when you hear a certain song or find yourself back in a particular bar. And I know your heart aches when another charismatic, bright person takes their life. I know remembering is hard, but forgetting would be worse.

"As you move through this life and this world you change things slightly, you leave marks behind, however small," Anthony Bourdain once said. "And in return, life — and travel — leaves marks on you. Most of the time, those marks -- on your body or on your heart — are beautiful." And then he added, "Often, though, they hurt."

Shares