It was late September in Aspen, Colorado, and the side of Ajax Mountain, looming over the rooftops of the town, was ablaze with yellow aspens, a forest fire of color in the hot sun; scrub oaks, burnt-orange and red adding their heat. I was sitting in the window of the Jerome Bar sipping a beer, and who did I see walking toward the bar down the street but one of my oldest friends, Cherry Jensen. We had been school kids together in Oberammergau, Germany, in the mid-1950s.

She was an Air Force brat and her family lived right below us in an apartment building on the post. We used to lace up our ski boots every morning and ski from our building’s front door to the school down the hill and stack our skis against the wall outside. We would change from our ski boots into regular shoes, and later, when school let out, change back into our ski boots and ski through the village of Oberammergau to the ski area on the mountainside just beyond, ski until the place closed at dusk, and ski home in the dark. There was snow on the ground up on the mountain from October to June. A day-long lift ticket cost one Mark. Twenty-five cents. It was a magical time.

Cherry had lived in Aspen for about 10 years, alternately waitressing at the Weinerstube Restaurant, skiing and traveling the globe, climbing mountains, hiking in Nepal, rafting down the Omo River in Africa, working as a boatsman on the wooden boats down in the Grand Canyon. Every time she put $1500 together, she would split, but now she was back in Aspen to pick up where she had left off in the spring. She was gorgeous – blonde hair, rosy-tanned cheeks, elegantly muscled body in a t-shirt with a day-pack on her back, moving through town like an antelope on her way to a spring.

I spied her through the window and waved. She came in, we embraced . . . it had been about a year since we had seen each other . . . and she took one look at me and said, you look like you need a soak in the Conundrum hot spring. Let’s hike up to there tomorrow morning.

Yeah, let’s hike up there, I found myself saying. I had no hiking boots, only a down vest and a sleeping bag. I put together some amateurish two-day supplies – a Jansport daypack into which I packed homemade fried chicken, an extra set of clothes, a knife, six cans of Coors and a pint of Henry McKenna bourbon in a special plastic jug that I picked up from a local mountaineering store. I thought briefly of coming up with a way to put the cost of the supplies on some magazine’s expense account tab, and then blew it off. The hike up to the hot springs with Cherry would pay for itself in healing, which I was definitely in need of.

The next morning, I met Cherry at her apartment. I looked like a fool in a hunting cap and mirrored Vuarnet shades. Cherry looked like she belonged there, in Austrian hiking boots and jeans and a loose-fitting shirt. Off we went, driving up one of the valleys outside of Aspen on a wooded dirt road in Cherry’s little Datsun, passing Jack Nicholson’s house on the way. Just beyond, the trees broke and a big meadow appeared. We parked, and on went the packs, Cherry’s larger than mine, and with a last glance around at the edge of civilization we began our hike.

The pain began immediately. There was a fire in my legs, pulling, straining in the thighs up through the lower back, a soreness across the shoulders, tightening in the lungs and a numbing sense of futility that the trail up the steep slopes would never end. It felt like the Army. But we climbed and climbed until finally I entered a kind of Zen of the mountain – watching grouse scatter and elk graze, crossing a creek once, twice, three times within a mile, gazing down into pools of trout, and we climbed on, past beaver lodges stately as twig mansions in the middle of small ponds at 9,000 feet, 9,500, 10,000.

Up there, things started to change. The light crashed through softly-blowing aspens, landing on the grass like droplets of clear water. Naturally, I was babbling away, telling stories about covering Evel Knievel’s jump of the Snake River, and Cherry listened and threw back her head laughing at the folly of telling tales in a place where the only story that mattered was all around us in the wind and the trees and the mountains. We climbed higher, and I fell into her natural silence, her easy awareness of everything around her. I felt a lightening of my senses. The creek, once a docile stream, now fell steeply over mossy rocks booming into deep pools.

This was the third extended hike Cherry had taken in as many weeks. The week before, she had gone up and over a nearby pass to Crested Butte and back to Aspen again, a three-day hike . . . by herself. Pack up and split. Sleep with the moon; walk with the sun. Now she was up there not alone but with me, walking along, thumbs hooked through her pack straps, balancing across 50-foot logs crossing the stream. And I was right there in the middle of her world where the biggest worry of the day became how far below the springs we should stop for firewood because the springs were above the treeline.

We decided we’d better gather some right then. She took off her pack and began breaking up sticks as big around as your arm. Collecting a pile, along with some kindling, she untied her pack-flap and strapped the wood onto her pack. I did the same with mine, and we put our packs on and started up again. With the firewood across her back, she looked like a miniature blonde elk.

We ended up on a flat ledge looking down at a hundred-foot waterfall and unpacked, laying out our sleeping pads and sleeping bags and getting a fire ready to light when we returned from the springs later that evening. Then we walked further up the trail and there, across a low marshy slope, we could see the hot springs – three indigo pools set in white scree dead-center in a bowl formed by a ridge and mountain peaks another thousand feet above us. Cherry was standing in front of me, taking in the view of the springs, legs together, just staring. There was a stillness in the air behind her that was easy to slide into, comfortable. Even though we had been friends since childhood, we were never very much alike. I was talky, moody, impatient, restless, insistent. Cherry was quiet, level-headed, also restless with the military brat’s need to keep moving, but she took her time, liked to go with the flow as we said back then. I had been in command of men in the Army, and what Cherry had commanded was her own body, moving it through space and time gracefully, gently, quietly and very, very elegantly.

Walking with her up to the hot springs that day I discovered there was spot-weld between our experiences. What we had in common was a drive to take chances and run the risk of failing. Every time I sat down at the typewriter, there was a chance what I wrote would suck. It wouldn’t sell, or nobody would read it, or those who did wouldn’t like it. For Cherry, risk-taking was skiing out of bounds down Walsh’s Gulch, cutting through powder, shooting through trees where no one else has skied, feeling the snow splashing up between your legs, zip around this tree, play chicken with that one. She broke a leg back there in the Gulch the year before and with the aid of a couple of companions, hauled herself through deep powder to reach a trail before the ski patrol did their final sweep. On their last patrol down the mountain before dark, two ski patrolmen strapped her to a toboggan and took her down the mountain. It was early January and extremely cold — not a good time to be stuck out of bounds after the last sweep.

Cherry turned to me: What do you think? She asked. In the late afternoon sun, the blue pools of the hot springs were like shimmering beads of sweat on the forehead of the mountain.

You told me it would be like this, but I didn’t believe you, I said.

We were believers, dreamers, like we all were back in the ’60s. Yet by that afternoon at the hot springs, what we were doing was in the process of being transformed for the mass-market. The Rocky Mountains were being turned into symbols for “freedom” by people like John Denver and Robert Redford. The language was about to take on a new tense, future anachronistic, to describe things that are over almost before they get started.

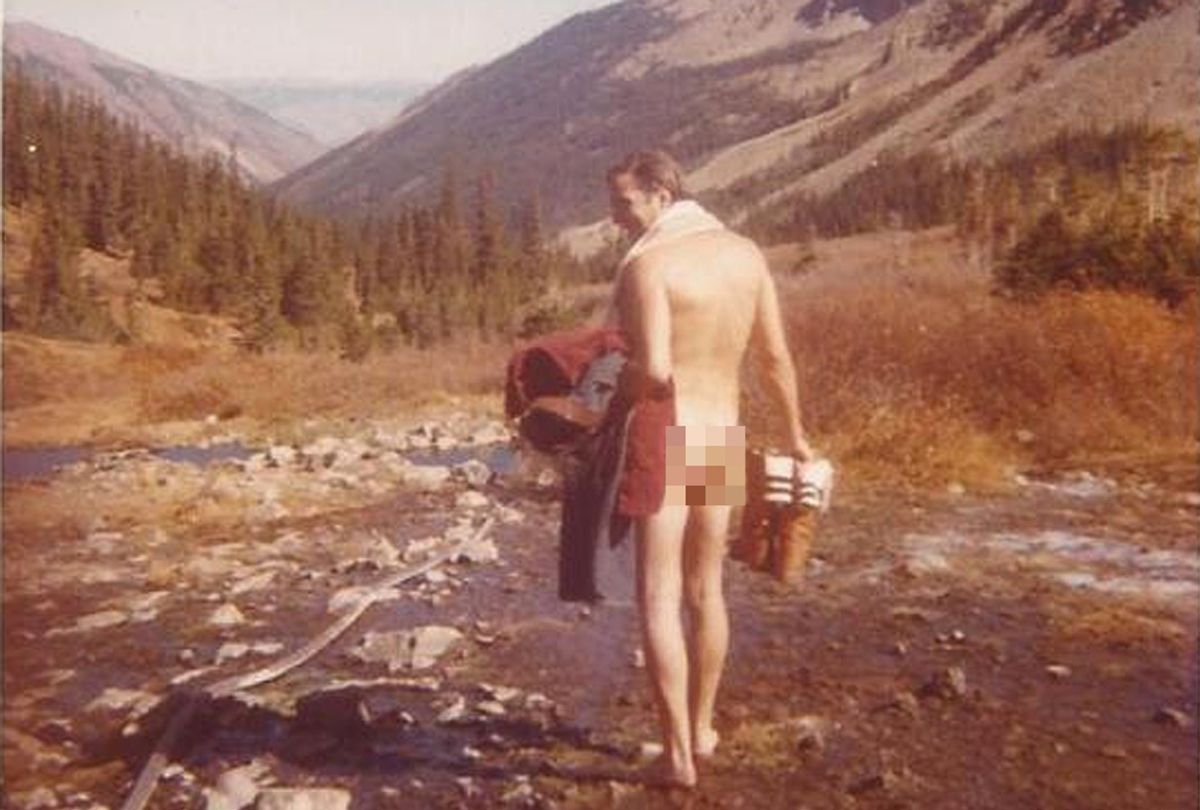

But we hiked up to the Conundrum hot springs because that night was a full moon, and we wanted to lie stark naked in the hot springs and watch . . . no, feel the full moon come up over the mountains. We undressed quickly before it got any colder — the temperature would plunge from around 70 to below freezing in a matter of minutes — and we jumped in. The water was around 105 degrees, a luscious hot caress of bubbly sulfurous fingers, five feet deep with rock ledges under the water to sit on with just your head above water. Three guys who had hiked over from Crested Butte were soon in the water with us, along with a couple of hippies who had been camped out up there for a week. The seven of us settled in to await the moon, whiskey, reefer passing around the pool, the cold, thin air chilling our lungs.

A couple of hours went by, then little by little the mountainside behind us was lit up by the moon, still out of sight behind the mountain. Then the light began moving down the mountainsides and it was about 100 yards away from us, moving much faster, then 50 then 25 yards, and suddenly the moon peeked over the top of the mountain, and the springs were awash in bright light, our naked bodies squirming below the surface, the moon now full and as white as the snow on the peaks above us.

More sips of whiskey, more tokes and we were out of the water into the 20-degree air, dried off and dressed and down to our camp. We started the fire and heated up my fried chicken and boiled some pasta and sat there eating, warmed by the fire, listening to the waterfall crash into rocks a hundred feet below us. Off with the clothes, into a deep sleep warm in our down bags. The next morning, we made oatmeal and coffee and headed back up to the springs for a last daylight dip, dried off and dressed and headed off down the trail.

We hardly talked at all, just tramped along pounding the trail, taking in the colors and wind and the constant burble of little rapids and falls along the stream. My head was as empty and clear as a water glass. I had always thought that turning it off and letting it flow was a bunch of hippie space cadet psychic burn-out stuff. But hauling myself up and down that mountain behind Cherry, watching her tanned muscles flicker in the sun, the whole thing looked different to me. Down at the bottom we loaded into her Datsun and drove back into Aspen and it was over . . . but it wasn’t. Something was nibbling at me so softly I could barely feel it, but I knew it was there, whatever it was.

Cherry and I hung around Aspen for a couple of days and one morning we jumped into my Dodge camper van and drove to San Francisco the long way, looping through every canyon and twisty stretch of road we could find on the map, stopping at night in little roadside pull-offs, making campfires, sitting around sipping wine, watching the stars wander by overhead. We were gone a couple of weeks, but then she had to be back in Aspen to begin her waitress job for the season, and I was due back in New York to turn in the stories I had written along the way.

I had been chasing something for the past few years, and I had managed to capture it once or twice in hotel rooms in Tel Aviv and Beirut covering the terrorism war, down in Washington covering Watergate. But this was different. This was something quiet and without boundaries. I came to think of it as the Cherry Jensen feeling, that sense of stillness in the air behind her as she walked steadily up and down the mountain. Yet even as quiet and satisfied as I was right then, I wondered, what, if anything, still counted?

Getting high still counted, but it didn’t feel as necessary as it had before. Chasing stories still counted, but I had come to realize that even the most exciting stories had a beginning, middle, and an end. Rock and roll still counted, but it didn’t take you the same places it once did. Being hip, man still counted, but at what cost?

I remember crossing the George Washington Bridge and turning south down the West Side Highway toward the Village and thinking I was glad to be back in New York. But I knew I had left a little piece of myself along that creek on the mountain, next to a campfire with my head resting in Cherry Jensen’s lap.

I turned left on West 10th Street off West Street and drove a couple of blocks and there was Allen Ginsberg bouncing along the sidewalk, a big grin on his face and a bundle of pages under his arm. I waved to him and he waved back. Hi Lucian, he called out cheerfully.

I was home.

Shares