At the height of his celebrity, Noel Gallagher would be caricatured by certain sections of the media as an anti-rap reactionary. After Jay-Z was announced as a headliner at the 2008 Glastonbury Festival, Gallagher was quoted as saying that hip-hop was "wrong" for an event that has "a tradition of guitar music."

In fact, despite his stance in 2008, in early adulthood Gallagher showed a cautious interest in hip-hop. He witnessed the seminal Def Jam package tour – which featured LL Cool J, Eric B & Rakim, and Public Enemy – when it passed through Manchester in 1987. Gallagher would later describe Public Enemy as "inspirational" and draw comparisons between hip-hop and his own music as kindred forms of working-class expression. Liam Gallagher’s backstory in this regard is even more interesting. Hip-hop was, apparently, the first kind of music he "really got into" (The Sun, 2009) As a 14-year-old in the late eighties, Liam was allegedly part of a BBoy gang, a group of kids who made a habit of venturing into the centre of Manchester with a piece of linoleum to breakdance in the city’s dilapidated public squares.

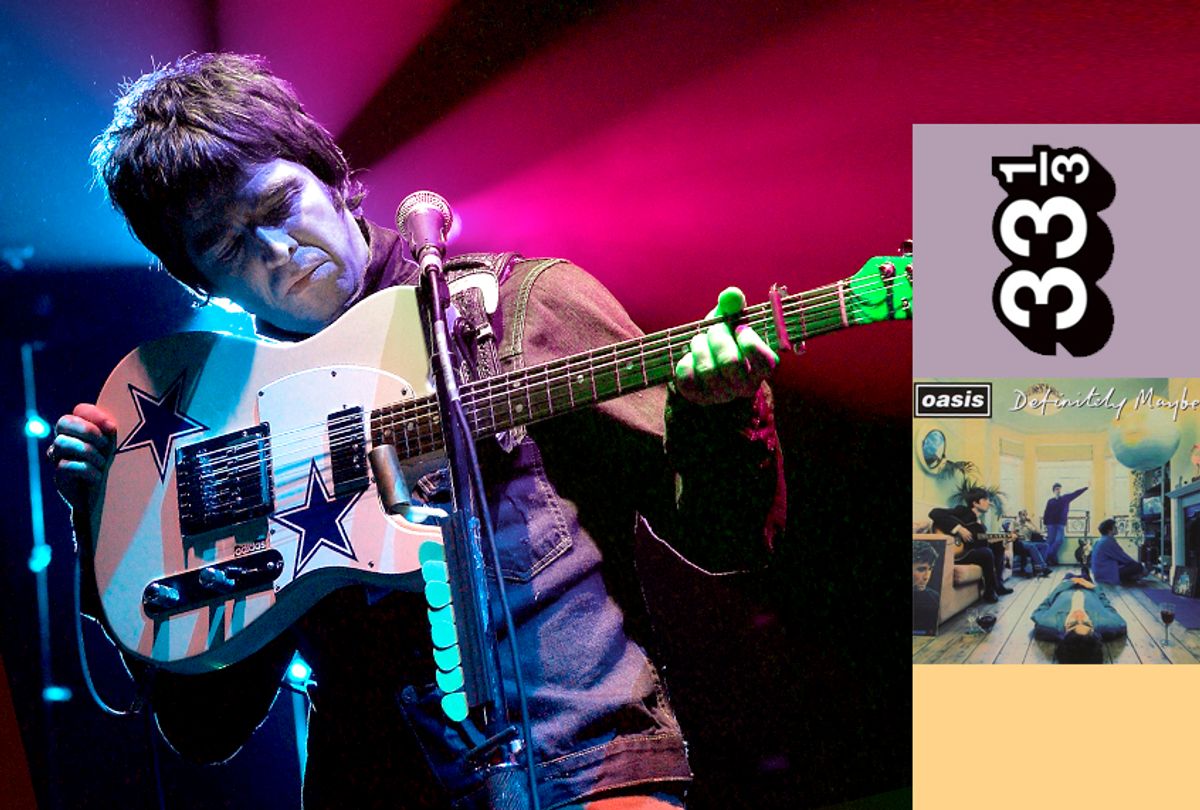

Whatever the extent of these actual encounters with rap’s by-products, Noel Gallagher’s comment that hip-hop and Oasis’s guitar-rock collage emerged from similar roots is surely credible. Oasis offered a rock equivalent to hip-hop’s brazen appropriation of pop-historical source material, a musical cut-and-paste that had deep affinities with – and was perhaps even loosely indebted to – the sampling culture that was a pervasive modus operandi of urban music culture during this period.

If Public Enemy spliced together James Brown, Funkadelic and recordings of Malcolm X speeches, Oasis wrote songs that glued together the Sex Pistols, The Rolling Stones, Burt Bacharach, Neil Young, Slade, The Smiths and The Jam, songs that grafted mangled fragments of anti-establishment rhetoric and council estate graffiti on to a base of guitar licks stolen from T. Rex and The Stone Roses (and even, more eccentrically, samples of Tony Benn speeches, and melodies borrowed from Wham! and The Glitter Band). If there was a difference between the two approaches, it was largely one of equipment – Oasis’s tools were Les Pauls and Marshall amps whereas Public Enemy had used turntables and the E-mu SP-1200.

When middle-class musicians resort to appropriation and collage it is often applauded as ‘allusion’ or ‘pastiche’; when working-class musicians do it they are dismissed as plagiarists, or prosecuted as outright thieves. The notion – still popular in some quarters – that Oasis were chancers who rose above their station by stealing other bands’ creative property is patronizing and ultimately untenable. Whatever can be said about their musical conservatism in later years, on "Definitely Maybe," Oasis’s appropriation of the past was just as valid, and just as creatively successful, as the sample tapestries on a work like Public Enemy’s "It Takes a Nation of Millions."

Partly, Oasis’s disregard for copyright laws can be put down to a simple lack of expectations. In spite of their fantastic hope, for all that they would claim with hindsight that they always knew they would become rock ’n’ roll stars, it is important to stress that much of Oasis’s early output was created in an environment of hopelessness, one in which they were understandably sceptical about their chances of breakthrough.

"Shakermaker," a joke song that ultimately developed into something much more interesting, is a classic example of Oasis’s cavalier approach to creative property laws, an attitude that arose ultimately from the fatalism of their position in the early nineties (as Noel Gallagher commented of "Cigarettes and Alcohol," another tune oriented around a direct sample-riff: "no one was going to hear it anyway"). The original version of "Shakermaker" was built around an adaptation of the 1971 song "I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing (In Perfect Harmony)." This was eventually a chart hit for the New Seekers, but it began life as the jingle for a Coca-Cola advert under the title "I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke." The melody and vocal cadences of "Shakermaker" are lifted wholesale from the Coke jingle, and its final verse originally included the verbatim line "I’d like to buy the world a Coke." The New Seekers sued successfully for $400,000 worth of damages when the tune eventually came to light, and the last verse was cut from the final version of "Definitely Maybe."

What’s notable about "Shakermaker" and its New Seekers steal is the sheer unselfconscious tackiness of its consumerist cartoon. The bourgeois wing of Britpop – Blur, Suede, Elastica – would get a lot of creative mileage out of half-disdainful, half-excited attempts to exploit the kitsch of the supermarket wasteland, the Dayglo nightclub and the Mediterranean package holiday. Indeed, the term "Britpop" was introduced originally as a way of describing the Home Counties pop-art parodies marketed by these bands from 1992 onwards. In the critic Jon Savage’s famous summary, the mainstream of Britpop was an "outer-suburban, middle-class fantasy of central London streetlife, with exclusively metropolitan models." Oasis’s working-class Mancunian version of this aesthetic was far less arch, and far more convincing, because it was realistic rather than romantic. If Blur indulged in highly contrived fantasies of street life, Oasis’s references to urban junk were casual and straightforwardly naturalistic.

In addition to its shameless borrowing of a Coca-Cola marketing campaign, "Shakermaker" references Mr Clean (a popular household cleaning fluid manufactured by Proctor and Gamble), Mr Benn (a children’s cartoon character of the 1970s), Mr Soft (an uncanny figure made out of white fabric who featured in a late eighties British TV advert for Trebor Softmints) and Mr Sifter (the name of a record shop in Burnage, Manchester, where the Gallaghers grew up). The title is derived from the Shaker Maker, a seventies toy that allowed children to mould small figurines with the aid of a mysterious powder called "Magic Mix."

There is no particular design behind the assembly of these commodities in "Shakermaker’s" lyric sheet, only a sense of freedom and entitlement about seizing everyday materials and attempting to fashion something irreverently beautiful out of them. Unlike their more self-conscious peers, Oasis did not alternately idealize and snigger at consumer culture from a distance. They merely replicated the objective reality of their lives without bothering to filter out the kaleidoscopic trash that littered the subconscious of their daily routines.

Shares