A.M. Homes would like to slip you into something uncomfortable. In her 30-year publishing career, the author has shown a unique penchant for cracking open the dark heart of human nature — usually with irreverent wit, devastating empathy and haunting shocks. The novel "The End of Alice" featured a pedophile as protagonist, while "May We Be Forgiven" kicks off accidents, adultery and murder and then goes from there. And when she explored her own origin story in the memoir "The Mistress's Daughter," she was just as unflinching and nuanced toward her birth parents — and herself — as she's ever been with her characters.

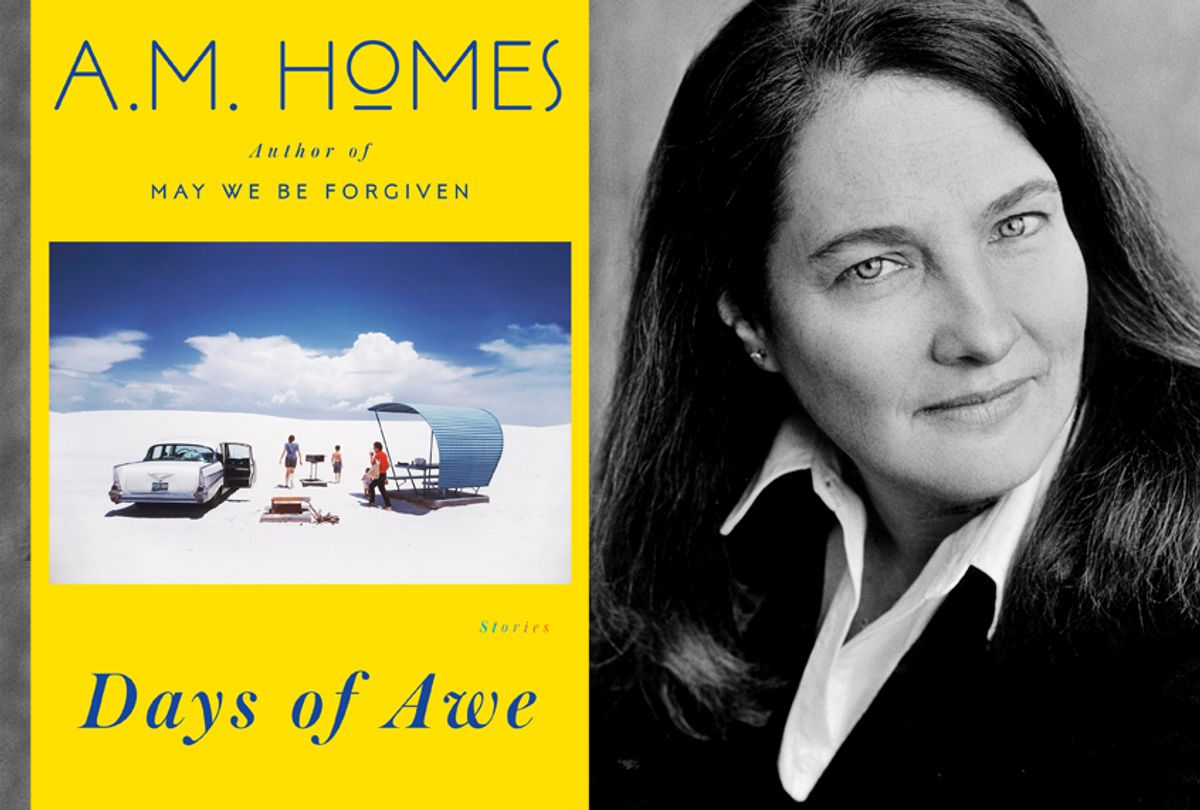

It's been 28 years since her breakthrough short story collection, "The Safety of Objects," and more than 15 since her last one, "Things You Should Know." Now she's returned to the form with "Days of Awe," a memorable assortment of new tales about family, love, death and an unqualified man who somehow stumbles into becoming a populist political candidate.

Salon spoke to Homes recently about her durable career, the bookstore exile of "women's fiction" and why Nixon is suddenly looking better.

This collection has been a long time in coming.

Part of it is that the stories themselves take a long time, and then there's the process of trying to shape what the collection should be and what the tenor of it is overall. Also, as with the previous two collections, I like to see where the stories fall in relation to each other a little bit and how the themes are tied. In some ways I think with the third collection, they're all of a piece in some way.

I wanted to ask you about how you feel this collection ties together thematically, because the stories are so different. There are very realistic stories; there are stories that are quite fanciful. You also have recurring characters. I’m wondering how you put all of this together in the way that feels very much like a statement.

I hope so, but I’m not sure. In terms of the variety of tone within it, I think it’s almost like a Mobius strip, where you can look at both sides of it. Sometimes, by being fantastical, it allows us to talk about reality in a more illuminating a way because it’s a different sort of an entry. It's just a way of playing and talking about things for me. In terms of putting it together, a lot of it has to do with looking at various stories in relation to each other.

This year feels like it is a special moment for the short story and particularly for women. The enormous breakthrough success of "Cat Person," and having a collection like Danielle Lazarin's "Back Talk" come out and be the success that it is, and then to have your collection coming out. These are stories written by women, very different, but also women just kind of stepping up and owning the short story form this year and making this gigantic impact in the literary world. Do you feel like the timing of it says something about where we are as readers?

All of these writers have been working on what they've been doing for many, many years, and then it does seem to have come to a point.

You said a few years ago you feel your work is very American. It feels like what it means to have an American identity is changing so fast right now. What does it mean to be an American writer, writing about American things right now?

Before the election, I was talking with my agent and my publishers about this book idea that I've been trying to figure out as a novel that was basically about the downfall of the American government. When I first talked about it they said, "That's science fiction, you don't write science fiction." I said, "I feel like there's something really interesting happening.”

Things are happening around us so fast. What it means to be an American is super important because there isn't a agreed upon American identity now. There's no agreed upon set of values or what democracy is, immigration, about who we are to each other. There isn't a sense of being united as a country. We're not seeing reflected back that idea that freedom is a basic human value. It's very tricky.

Seeing how teenagers have risen to the challenge, have really taken charge of the narrative, is exciting. It is also terrifying because it is such uncharted waters.

I think that things like the teenagers in Florida are really challenging the status quo. It's amazing, and they're doing it in a different way than the teenagers of the early 1960s or mid-1960s did. What worries me is that people are forgetting their relationship to history. If [you] don't know what your history is, it's very hard. The absence of history is problematic.

I think that the middle of America, and the people who were coal miners and worked in factories, really feel lost. And they're lost because our system is not giving them new kinds of jobs. The perception is that their work has gone to immigrants, which isn't true. I understand why they could feel America has lost something. It's lost them. And they want to feel part of America and feel part of their country.

And it's easier to conceptualize an idealized past than it is to construct a vision of a future.

If you look at people like Martin Luther King, John Kennedy, Obama, they led on dreams. I think we have gone the way of the tax rebate: “I'll give you $300 for your family if you vote for me.”

Look at Nixon. Nixon started the EPA. Nixon was open with relations with China. I think it's fascinating to look at somebody who we see as a truly complicated president and then look at where we are now, like “Wow, what are our goals for ourselves as a country?" They're not clear, and also interestingly, they're not very inward looking. There's not a lot of, "Why aren't we doing more infrastructure projects that would employ people? Why don't we have programs for veterans that would bring them back and give them jobs with other veterans so they have a sense of community?" There are so many things that we could be doing that are not difficult to do, but that's not where the lens is. I'm interested in and fascinated by it. I guess I would love to see some fairly regular but smart person run for office.

It's also become a money game. There's so much about how much money can you put into it. Trump capitalized on free media. Nobody really talks about that, but early on it looked [like] there were six New York Times crews following him. I asked one of the editors, “Why are there six crews following him?” He said, "Because he makes news." That's part of what happened in his over-the-top speeches. All of a sudden he made news, so he got [an] enormous amount of essentially free advertising every day. It's a complicated thing.

When I get very despairing about everything, I think, "Just because I don’t have the map doesn’t mean my kids don’t, or it doesn’t mean my kids won’t draw a new one."

I have these students who are so incredibly smart and don't know anything. I say to them, the careers they’re going to have in 10 years don’t exist right now. Their future, smart as they are, is going to not be based on facts they can learn and papers they can write right now, but it will be based on what they can dream for themselves. They're our leaders for tomorrow. I think if your leaders don’t have an imagination, they’re not going to be good leaders because they’re going to follow directions.

How do you teach somebody to think for themselves or make a decision? I think the two things that will help a young person are history and economics. I think really, economics relates to all of it. That’s where everything is coming from at the moment. And then, what does it really mean to be a leader?

It’s so devalued in our culture: Do you communicate? Do you know how to present your ideas? Do you know how to make a case for you ideas? Do you know how to talk to another person?

I want to ask you one more thing, because you have one of the most durable careers in literature. For a fiction writer you’re in a very small pool, and especially as a woman. I’m wondering, how has the game changed for you? What does it feel like doing it now?

Part of me honestly thinks there’s no way it’s been 30 years. That’s crazy. In my mind, that's just not even a possibility. The other piece that really bothers me is that I came of age at a time when the literary world was divided and there was no such thing as a fiction section. There's women's fiction and gay fiction. Everything became very fragmented. I think in many ways being a woman who writes has really been kind of difficult actually, because I think of what kinds of books would be appealing to the young men and women I think I’m writing about. The truth is that the expectation in America is women writers write about domestic things. English writers seem to be, for want of a better word, allowed to write about these large, social and political ideas. Being able to go to Europe and touring, there are tons of people of very diverse crowds, and that’s kind of great. Here when I’m talking to people, sometimes I’ll be talking to a guy and he'’ll say to me, “Oh, I’m here to tell my wife about your books.”

I feel in some ways there are probably young people who would like my stories and novels, who don’t even know about them. I’d like to think that maybe in this world we're in right now where things are changing, that there’s slightly less divide in how books are marketed and sold and even put on bookshelves. When bookstores divided into sections, they took black writers out of fiction and women writers out of fiction. That really meant there was a large section of the book store was just the white guys section.

The flip side is, how can we legitimize writing about the domestic? How can we write about women’s stories in a way where we're not just shipped off to the literary ghetto?

Last year a student came to me and said, "I'm taking a course in 20th century fiction. Is it true women weren't really writing in the 20th century?" The reading list was Faulkner and all these books. I said, "Let me make a little list for you. Here's Eudora Welty and Flannery O'Connor and all these other women. Give this back to your professor and tell him, 'Hey, I just found out there were women writing in the 20th century.'" If it's not brought into this in a different way, then [the writing] stays separated. And then people have to take "Women’s Literature," or "Gender in Fiction," which isn’t the same because then it also becomes self-selecting of young women looking for place to talk about women’s writing.

I was giving a talk with another writer and some guy said, “I haven’t read your books, but I have a question.” I said to him, “I’d be happy to give you a copy of my book,” and he said, “I don’t read books by women, but I do have a question." He really didn’t want to hear it. Grace Paley said that women have always done men the favor of reading their work and men have not returned the favor. Grace was a feminist, but as importantly, Grace loved men. I think that what she taught me was that you can be a feminist and advocate for equality and you can also love men. That’s always been really important because I do love men. I write a lot about male characters. I also think women’s lives and the roles that women play and the relationships that women have are equal to the lives men lead.

I love writing so much. I feel enormously lucky. My books come out around the world, and that also means to me as an American writer, the stories have resonance in all countries. They come out in Korea and they come out in Hungarian and Romanian. That, to me, is secretly my favorite part of it, that they travel.

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Shares