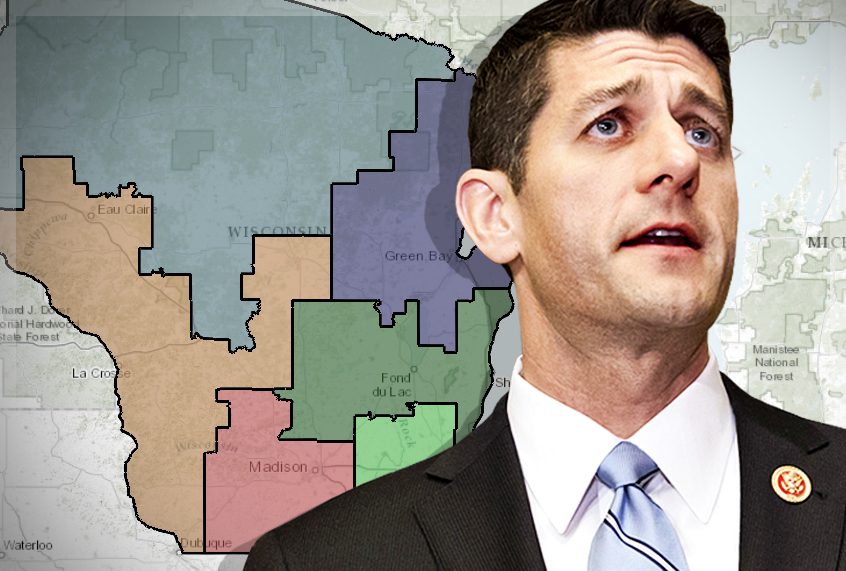

We’ll soon know how the U.S. Supreme Court will rule in two key partisan gerrymandering cases, one from Wisconsin and the other from Maryland, which have the potential to remake how our congressional districts are drawn.

Whatever the court determines, multiple lower and state court decisions should finally put to rest one important debate: Is the durable Republican congressional advantage across otherwise competitive purple states a natural geographic edge or an unnatural upper hand obtained via extreme gerrymandering?

In Wisconsin, North Carolina and Pennsylvania, Republicans and their expert witnesses have defended GOP supremacy on legislative and congressional maps as the result of natural sorting. Democrats, they have argued, cluster themselves in urban areas; Republican voters spread themselves more efficiently across suburbs and rural America.

Whether or not Democratic clustering stands in the way of fair maps in these states, however, is a question that can be tested and adjudicated. This argument has now been rejected by state supreme court justices, as well as federal judges appointed by both Democratic and Republican presidents. Several courts have reached the same conclusion. The problem in these states is aggressive gerrymandering, and there’s nothing necessary or organic about it. It’s Big Data, not the Big Sort.

Some judges have relied on new computer-driven, social-science metrics to dismiss the “self-clustering” argument. Others have carefully tested and evaluated competing expert claims. And some simply could not ignore the paper trails left by mapmakers themselves: Dozens upon dozens of draft maps, each more partisan than the next, revealing the surgically crafted GOP advantages to be anything but self-serving or geographic inevitability.

In the Wisconsin case, a panel of three federal judges found that while the state’s political geography afforded Republicans some nominal advantage, it “simply does not explain adequately the sizable disparate effect” in the 2012 and 2014 state legislative elections. That 2012 race was the first run on the current maps, drawn entirely by Republicans in a top secret, eyes-only “map room” headquartered in a politically connected law firm across from the state capitol in Madison. It produced 60 Republican seats and just 39 for Democrats in 2012 — even though Democratic candidates amassed 174,000 more votes statewide.

Republicans defended the maps in federal court by suggesting the GOP advantage was “unavoidable” due to clustered Democrats and more evenly spread Republicans. Any districting plan, they argued, would favor Republicans naturally. They presented expert testimony, however, that the court found wholly inadequate to explain the historic Republican lean over two cycles on these maps. If the geographic advantage was inevitable, the Court suggested, it must not be possible to draw any maps without that partisan slant. But Republican mapmakers had produced “multiple alternative plans” without that dramatic bent, despite the modest pro-GOP geography. Fair maps could be drawn, despite Wisconsin’s political geography. Republicans drew them — but merely to use them as a starting point.

Republicans began with a map that would have given their candidates, with that modest geographic advantage, an edge in 49 districts. From there, the partisan operatives drawing the maps refined the lines using detailed voting indexes and precise demographic data. Each time, the “expected partisan advantage increased.” Even the names of these plans — “Assertive” or “Aggressive” — showed off the edge Republicans expected to receive. The final map expected to yield 59 seats, 10 more than the initial versions — and only one shy of the actual 2012 results.

“Benign factors” like geography “cannot explain this substantial increase” in Republican advantage, the court found. “The drafters established this finding themselves; they produced several statewide draft plans that performed satisfactorily on legitimate districting criteria without attaining drastic partisan advantage.” The argument that geography mattered more than gerrymandering “lacked specificity and careful analysis.”

The arguments were similar in Pennsylvania’s state Supreme Court last December. Republican leaders cited geography — specifically clustered Democrats in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh — to defend the constitutionality of congressional maps that awarded themselves 13 of the 18 congressional seats in this ordinarily blue-leaning state. That 13-5 edge endured throughout 2012, 2014 and 2016, even in cycles when Democrats earned more votes.

While the Republicans’ own draft maps betrayed that claim in Wisconsin, the Pennsylvania case swung, in part, due to precise statistical methods that revealed how surgically these lines had been crafted to give them the pretense of geographical inevitability. Dr. Jowie Chen, one of the nation’s leading experts on redistricting and political geography, used a simple mean/median test and demonstrated a “very statistically extreme outcome that cannot be explained by voter geography.”

Under another expert standard found convincing by the court, the Republicans’ geographic edge was less than 1 percent prior to this decade’s maps. The 2011 plan, however, had increased that advantage to “between 15 and 24 percent.” In other words, the court found that “in its disregard of the traditional redistricting factors, the 2011 Plan consistently works toward and accomplishes the concentration of the power of historically Republican voters.”

The statistical evidence also burnished basic common sense: After all, Democrats won 12 of the state’s 19 congressional seats in 2008, when their candidates won a majority of the vote statewide. Similar results in 2012, however, handed Republicans 70 percent of the seats, even as Barack Obama easily defeated Mitt Romney statewide. Pennsylvania Democrats did not self-sort themselves in any dramatic way between 2008 and 2012; rather, they were clustered by partisan operatives into wildly spirographed districts that resembled “Donald Duck Kicking Goofy.” The Court ordered the entire statewide map redrawn as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. The new maps are expected to create a delegation that actually reflects the state’s political opinions.

Likewise, in North Carolina’s partisan gerrymandering case, Common Cause and League of Women Voters v. Rucho, another panel of three federal judges carefully weighed and then overwhelmingly rejected the idea that Democratic clustering in urban areas — or “natural packing” — explained maps so pro-Republican that the GOP won 10 of 13 seats in this purple state. They based this finding, in part, on an admission by the GOP’s own expert, who conceded that the congressional maps “cracked” Democratic clusters and submerged them in GOP-leaning districts unlikely to elect a Democrat.

Then the court turned to the numbers. Judges were convinced by the statistical work of Chen and Duke professor Jonathan Mattingly — who simulated almost 25,000 sets of maps using traditional districting procedures and found no evidence to conclude that the GOP advantage was explained by the state’s political geography. The Republican legislators defending the maps, the Court concluded, “have not provided any persuasive basis” to question the professors’ “methods, findings and conclusions. Accordingly, we find that North Carolina’s political geography does not explain the 2016 Plan’s discriminatory effects.” This court, as well, ordered a new congressional map for the 2018 elections; the U.S. Supreme Court stayed that demand pending the resolution of the Wisconsin and Maryland cases.

Democrats do cluster in urban areas, but as these courts have found time and again, that generates only a minimal electoral advantage for Republicans. Maps drawn with fairness in mind can and do overcome that easily — whether they are neutral districts created by supercomputers or the work of high-school students in Ohio and Pennsylvania, who regularly draw less partisan maps than the ones chosen by politicians (who then blame geography for their biased choices).

Yes, there are states where geography affects fair representation: Republicans in New England and Democrats in the Deep South are unlikely to see their views represented in Congress without multi-member districts and ranked-choice voting, the reforms laid out in the Fair Representation Act proposed by Rep. Don Beyer, D-Va.

Likewise, the siloing of our politics and our media contributes to polarization and has dangerous consequences. We choose whether to hide conservative friends on Facebook or to watch cable news that confirms our sense of the world. But where we live does not change the ability of a partisan mapmaker to draw lines that carve and cluster voters within districts that are finely tuned to produce a specific outcome.

The political media too often attributes the GOP’s structural edge in the House of Representatives — estimated by the Associated Press and NYU’s Brennan Center to be between 16 and 22 seats — to both gerrymandering and geography. This “both sides” conventional wisdom obstructs a real understanding of today’s sophisticated, high-tech gerrymanders — and provides an incomplete picture of the competitive, 50/50 states where they are at their worst.

Whether or not the Supreme Court this month finds a clear constitutional standard to determine when either party pushes those lines too far, it’s time to end the myth that voters have done this to themselves.