Oh, now I get it.

Now I understand why so many chefs dread Pete Wells’ mug in their dining rooms and his signature on their report cards.

Last week, Wells, restaurant critic for The New York Times, wrote a review occasioned by the publication of my book about the American chefs of the 1970s and 1980s in the Times’ Book Review.

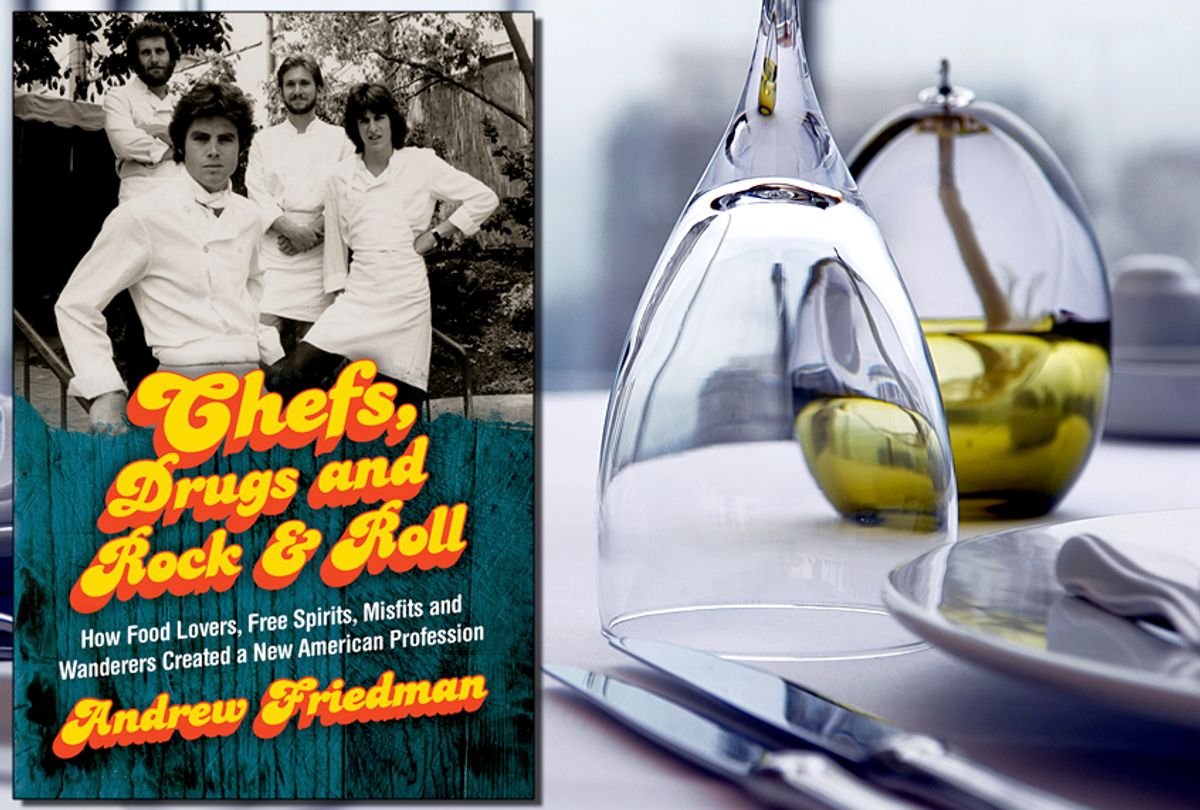

Because of the title of the book, “Chefs, Drugs, and Rock & Roll: How Food Lovers, Free Spirits, Misfits, and Wanderers Created a New American Profession,” Wells opened with several paragraphs connecting it to the #MeToo movement, describing a perceived failure to address the issues it has raised. “Could any title, with the possible exception of ‘The Harvey Weinstein Massage Manual,’” he offered, “sound more off-key now?”

At best, the lede was intellectually dishonest; the Weinstein crack gratuitous. Any professional writer of Wells’ experience knows book titles and text are locked down months ahead of time, which in this case meant long before The Reckoning was at hand. On my podcast last week [about the 4 minute mark], I expressed my disappointment in this strain of the review, while also vowing not to delineate other concerns, lest I come off as defensive. Privately, however, I marveled that he was so unmoved by the culinary revolution at the heart of the book that so many find exhilarating and which, among other things, helped elevate food writing and restaurant criticism to ever-greater heights over the years, a benefit he enjoys as much as anybody on the planet.

But a flood of commiserating emails, texts, phone calls, and Instagram messages from Wells’ usual subjects (chefs) rolled in since then, making it clear that, having been reviewed by him, I suddenly possessed rare insight into his unique place in the industry. For somebody who writes about chefs, and is always seeking to understand them, this was a welcome silver lining.

Of course, no critic is universally loved, or even liked, but as anybody who knows New York City hospitality professionals can tell you, they regard the current Times critic with unprecedented skepticism and disdain. It’s not his job to please those he lords over — that’s understood. But if he were doing that job with more integrity and humanity, fewer would consider him a villain. Many on the receiving end find his reviews petty, personal, mean-spirited, and joyless, and discern between the lines an antipathy toward chefs and fine dining, and downright disregard for the rigors of their work.

“My issue with Pete Wells is that it seems like he has an axe to grind with fine dining, specifically French fine dining,” says a New York City fine-dining chef. “I think he took a shot at Daniel Boulud, Michael White, Thomas Keller, and of course [Joel Robuchon in] the recent Atelier review — those have been the big ones. It’s like, walk into a bar and take a swing at the biggest guy in the room . . . he seems to have it in for expensive and formal, but those restaurants aren’t for everybody. Not everyone gets to fly first class. That doesn’t make it objectively bad.”

“When we talk about him it devolves very quickly into four-letter words,” says one Michelin-starred New York City chef (one who has not been reviewed by Wells). “When we talk about his writing style, his general approach to restaurants, it’s not even a question of whether he’s wrong or inappropriate. It’s just a question of the level. There’s this sense of confrontation. He’s like a ten-year old with a pile of ants and a magnifying glass. It’s like he’s here to tear it down.”

Many observers also believe he’s exploiting the hallowed role of Times critic to further his own agenda and career — as if Donald Trump were using the presidency to land his gig on “The Apprentice,” instead of the other way around. They grudgingly acknowledge his intellect, wit, and writing talent, but feel that he uses them for ill, or self-promotion, or both.

“I’m sure you’ve heard this from several chefs already,” messaged a former New York City whisk I only know via Instagram. “But I will say that [the] comments in Wells’ review are indicative of the reasons that chefs in NYC have such a problem with Wells. It’s lazy journalism at its worst. Or better yet, ‘how do I get more clicks?’”

“Wells has always wanted to take down ideas and goals that form the very thesis of your book,” Barry Wine, chef-owner of The Quilted Giraffe — a restaurant given four stars by The New York Times during the 1980s — wrote to me in an email following the review. “He has no respect for those who strive for excellence, for those who want to transform the status quo, for those who toil because they believe that things can be better — restaurants included. He dabbles in being uninformed, callous, and wallowing in populism, intentionally misinterpreting subjects on which he should know better. His quip that so many people in your book — me included — lacked knowledge of food basics takes something poignant and turns it into something damming. He misses the whole point.”

The fear of retribution keeps all but a very few contemporary chefs from speaking out, but I’m not opening a restaurant any time soon, so find myself in a singular position, a Wells survivor willing to share the experience, and shine a light on what fuels the industry’s distaste for him. So, for those who are interested, here you go:

This isn’t my first at-bat as an author; in addition to my own books, I’ve collaborated on dozens of cookbooks and memoirs. So I’ve received my share of criticism. It’s not fun, but I’ve never failed to absorb it and move on. Not when a colleague referred to a cookbook I co-authored as a “cream-crusted dinosaur,” or even when the AV Club called my first nonfiction effort a “half-baked attempt at book-length reportage.” (ouch)

I’ve long believed that if you’re going to put yourself out there, you take your lumps in stride. Or, as Jeremiah Tower, who refers to being in the spotlight as “riding the tiger,” once told a friend who’d been burned by a journalist: “You got on the tiger. No complaining, no explaining . . . shut up and either get off the tiger or just make it better for you than worse.”

In this case especially, you’d think I’d be able to shut up, having enjoyed a hell of a ride in the three months since the book was published to mostly positive reviews. If I’m honest, the book probably even experienced a sales bump resulting from inclusion in the Times’ “Summer Reading” issue.

So, if I’m no worse for wear, why has this article — in which are actually buried a few compliments (look for “Essential – The New York Times” on the paperback’s cover) —been so hard to shake?

After much cogitation, I’ve sorted out why closure eludes me, but not before enduring firsthand the emotions so many chefs do after going through the Wells spanking machine and coming out the other end not so much criticized as aggrieved.

Wells’ article reads more like a think piece than a critique, which isn’t unusual in the Times Book Review, but he blurs the lines, making editorial suggestions and lamenting the absence of mom-and-pop restaurants and the Immigration Act of 1965 from the book, rather than offering them as complements to it. They are interesting footnotes, to be sure, but neither is indispensable to the story I explicitly set out to tell; any disbelievers can read the Author’s Note and Introduction for themselves. Wine makes a direct connection between this and the Joe Lunchpail pandering of so many Wells restaurant reviews: “He goes way too far in talking about class and privilege as the impetus for the revolution. The mom-and-pop restaurants he attempts to elevate were the examples of the problem we sought to change. He should not be elevating them and denigrating the change agents.”

A point-by-point refutation of what few direct criticisms he does make can only sound like sour grapes. And, besides, I freely admit to agreeing with some of them. It’s essentially objective, however, to observe that much of his contextualizing reveals a misunderstanding of the restaurant industry and disrespect for the professional cooking trade that is the salt in so many wounds. This is true from the first paragraph — his blithe statement that some members of the Woodstock generation “decided it would be fun” to cook for a living glosses over the grueling, manual work they performed and the great financial risk many took to realize their ambitions — to the last, where his comment that chefs of the era “drew up the drawbridge” couldn’t be more off the mark; to this day, chefs take on aspirants who show up unannounced at the back door seeking their first break, and lifetime mentorship remains a rare and defining tradition. And his misplaced preoccupation with current events unfairly paints all chefs of the era with the brush of scandal.

In short, reading the piece was an out-of-body experience and case of mistaken identity rolled into one, like watching a doppelgänger get jumped in an alley. Still, if the review hadn’t been printed in the New York Times, I wouldn’t have spent more than five minutes thinking about it. But there’s the rub; for most readers, it’s the official word on the book by the paper of record. It’s confounding to be so misunderstood and misused after being deemed worthy of attention by every writer’s dream publication.

Of course, for all of these reasons, to chefs and restaurateurs, I’m not a lucky scribe who got reviewed in the Times, but rather the latest victim of Pete Wells, who usually confines himself to restaurant reviews and related articles.That this assignment landed on his desk produced no shortage of conspiracy theories from the chef community: “He’s jealous that you thought of the idea first.” “He disapproves that you’re friends with chefs.” “He saw the book getting lots of coverage so had to weigh in.” “His colleagues are winning Pulitzers for #MeToo reporting so he wants to cover that every chance he gets.”

Most chefs I heard from also saw in that Weinstein crack alone the snark, opportunism, and lack of basic decency they consider Wells’ MO. Many of our greatest critics believe a negative review should be as painful to write as it will be to read. Wells seems unburdened by such concerns; in this case, rather than commenting about the title in passing, he makes a tone-setting, lowest-common-denominator joke that can only compound what he deems unfortunate timing for the book’s author. “His reference to #MeToo and Harvey Weinstein is an extension of what he does in reviews when he subtlety creates negativity for the ‘sins of others’ which have nothing to do with the restaurant,” wrote Wine.

Echoes the Michelin-starred chef, “He goes straight to editorializing about something like a cocktail; he walks into a restaurant and fixates on a fairly inane detail and takes it completely out of context. He’s like Shel Silverstein’s Yipayuk.”

Some consider Wells’ review of Guy Fieri’s Guy’s American Kitchen & Bar — written in 2012, his first year on the job — a classic; to the rest of us, it was proof positive of his intentions and priorities. The piece ranks as one of the most clicked-to Times articles of all time. Good for him. But how, one might reasonably wonder, did he justify not expending that precious real estate on a restaurant the average Times reader might actually have considered visiting, perhaps Apiary, where veteran New York City chef Scott Bryan — a recipient of three stars from the Times at his prior restaurant Veritas — was installed from 2009 to 2014, and which Wells never got around to reviewing?

Says the Michelin-starred chef, “He is perpetuating with something like the Guy Fieri review a void in the industry by giving attention to people who shouldn’t get it … a critic should choose his subject carefully, give it the respect that it’s due, and respect that [restaurants are] the heart and soul not just of one person but of a group of people and an integral part of New York City life and culture.”

“I felt like when he took over as a reviewer it marked a change for the New York Times and who the audience was,” comments a former New York City chef who has been reviewed by Wells. “In my opinion, the Times review doesn’t carry the same kind of weight it did in the 1980s and 1990s. It used to review restaurants of a certain caliber . . . . Some of it to me seems pointless. The Guy Fieri review was a waste of time for all involved. Are you a comedy writer? I’m just not certain what his purpose is as a restaurant reviewer. It needs to be re-defined in a public way. It’s not a [restaurant] review anymore; it’s a social critique. I stopped reading them. ”

“Even if Friedman doesn’t manage to tell the whole story . . . ” Wells begins his final paragraph on “Chefs, Drugs, and Rock & Roll.” But what narrative spanning multiple states and two decades, about any subject, has ever told the whole story? Do restaurant reviews describe every dish on the menu, every wine on the list, every nuance of seasoning and service? Or was “whole story” inadvertent code for “the story Pete Wells would have told,” and is that really the point of a review?

All professionals — chefs and writers alike — should be able to take in legitimate criticism respectfully delivered; but expecting them to sacrifice their work to the cause of a critic’s self-aggrandizement is a bridge too far.

As a friend put it after reading Wells’ piece, “I was hoping your book would be reviewed by the Times. Maybe someday it will.”

Shares