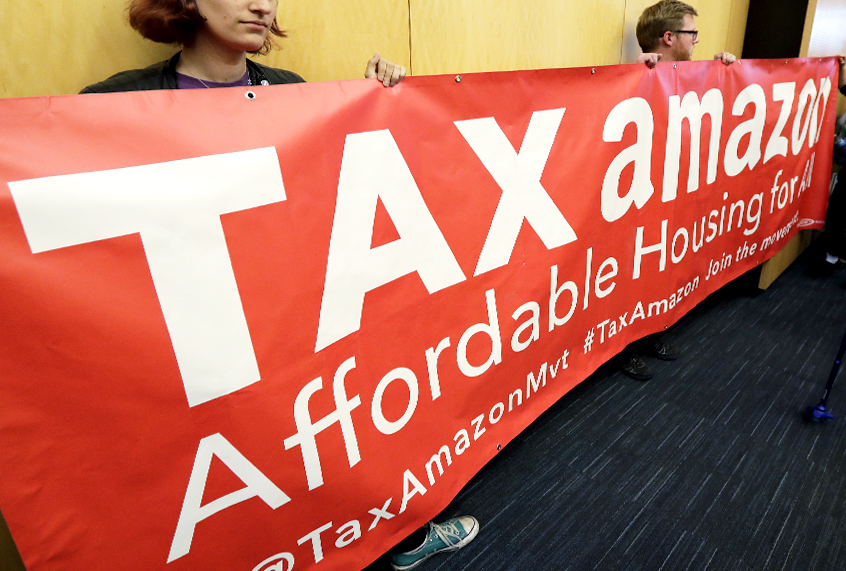

In May, Seattle’s City Council unanimously passed the employee headcount tax, which would tax companies in Seattle that make over $40 million a year to the tune of $275 per employee. The funding was to be allocated to homeless shelters, affordable housing and public health services.

Then, on Tuesday, the city council voted to repeal the ordinance after an Amazon-backed campaign succeeded.

What happened in the span of a month says a lot about the power of tech companies and their willingness to bulldoze even a nominal tax that would have helped lift thousands out of poverty.

The Seattle City Council’s 7-2 vote to repeal the ordinance was spurred by a referendum led by the No Tax on Jobs Coalition, an astroturf movement that, according to filings with the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission, included Amazon as a lead contributor to the campaign. Other supporters included grocery chains and real estate companies. Starbucks also supported the movement.

In May, the Seattle Times reported that Amazon paused construction planning on a new downtown Seattle tower before the first vote on the headcount tax — a political move that was widely perceived as a threat. Disconcertingly, even in one of the country’s most progressive cities, corporate opposition was able to stop a tax that would have helped the homeless population at a minor cost to Amazon. Note that Seattle has the third-highest homeless population in the United States, after New York and Los Angeles. Meanwhile, Amazon had revenues of $177 billion in 2017.

“Over the past months, big business launched a ferocious propaganda offensive against paying their fair share of taxes,” Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant told Salon in a statement. “The local newspaper (which itself would be taxed) ran near daily articles editorializing against progressive business taxes, Amazon threatened to lay off thousands of workers, and big business poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into a campaign to spread misinformation.”

“This is nothing new, and it is not a surprise,” the progressive councilmember added. “In 2013 Boeing extorted almost $9 billion in tax breaks from Washington State by threatening to move jobs, and once the state legislature met their demands, Boeing moved the jobs anyway and started attacking workers’ pensions.”

Sawant said Seattle’s latest upset undermines an important progressive movement.

“The affordable housing movement, the thousands of dedicated and self-sacrificing volunteers, we have been preparing to answer the misinformation of big business, knock on doors, and win a conscious majority in support of taxing big business to build affordable housing,” Sawant said. “Council’s backroom deal and cowardly capitulation undercuts the affordable housing movement before that fight has even started. We have no choice but to organize, independent from the Republicans and Democrats who are so beholden to corporate campaign contributions, to rebuild a movement to tax the 1% and to build the housing working people desperately need.”

Considering that these so-called corporate bullying tactics worked in Seattle, many are wondering what this means for other cities trying to pass similar legislations. Can big businesses unilaterally torpedo taxes that would fund needed social services — which, ironically, are often necessitated by the social havoc wrought by said tech companies in the first place?

“Activists in other cities should learn from the successes and failures of the affordable housing movement in Seattle,” Sawant said. “Big business will fight back against any attempt to shift the tax burden off the backs of working people, and the only way we can stand up to that is with a mass grassroots movement, deep enough to knock on doors, discuss in workplaces, and systematically answer the lies and misinformation big business will spread.”

Sawant suggested it might take a larger grassroots movement to successfully fight back.

“We need a united movement of housing justice activists, socialists, labor unions, organizations fighting discrimination, and other progressive people and organizations,” she said. “Our movement needs our own working-class elected representatives independent of the Democrats and Republicans who base their power on campaign donations from big business.”

Later this June, the City Council in Mountain View, California — where Google’s headquarters sits — is scheduled to vote on whether to put the “Google headcount tax” on the ballot in November or not. Similar to Seattle, it is meant to tax bigger corporations like Google in order to create funding for civic needs; in this case, transportation. Google would reportedly be taxed about $5 million if passed, out of a predicted total of $10 million — chump change for a corporation with a revenue that exceeds $110 billion.

Mountain View mayor Lenny Siegel told the Washington Post that he is not concerned the city will have a similar outcome like Seattle, though.

“It appears that we have a better relationship with our business than Seattle does,” Siegel said.

According to CNN, Cupertino — where Apple headquarters is located — is in the early stages of considering a headcount tax, too.

San Jose, Sunnyvale, and Redwood City — all within the circumference of Silicon Valley — have an existing variation of an employee headcount tax. The concept is nothing new, yet it has gained more attention in the wake of Amazon’s resistance in Seattle.

Amazon also appears to be a unique tech conglomerate when it comes to sharing the wealth with the cities it occupies. Researchers have said that Amazon’s presence does not necessarily boost local economies, despite the company’s claims during campaigns to open fulfillment centers in rural cities in return for tax breaks.

Prior to the referendum vote on Tuesday, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan and members of the Seattle City Council exuded defeat in a joint statement, narrowing in on the battle between local government and big businesses.

“Over the last few weeks, these conversations and much public dialogue has continued,” the statement read. “It is clear that the ordinance will lead to a prolonged, expensive political fight over the next five months that will do nothing to tackle our urgent housing and homelessness crisis.”

Meanwhile, those who could have potentially benefitted from the tax, such as Youthcare, an organization that provides services such as shelter to Seattle’s homeless youth, were disappointed by the politics of the situation from the beginning,

“This was a chance to make a critically-needed investment in affordable housing and support services for people experiencing homelessness and those at risk,” Melinda Giovengo, Chief Executive Officer & President, told Salon in a statement. “We hope that this has sparked an ongoing discussion around supporting lasting solutions for ending homelessness, including employment and education programming for young people and an increase in safe, affordable housing options.”

Arthur Padilla, Interim Executive Director of Roots Young Adult Shelter in Seattle, echoed that sentiment.

“This process really never got to the point where we were considering what we could do with increased funding,” Padilla told Salon in an email. “The politics surrounding these issues drown out the voices and the real needs of young people and that’s where we stay focused.”