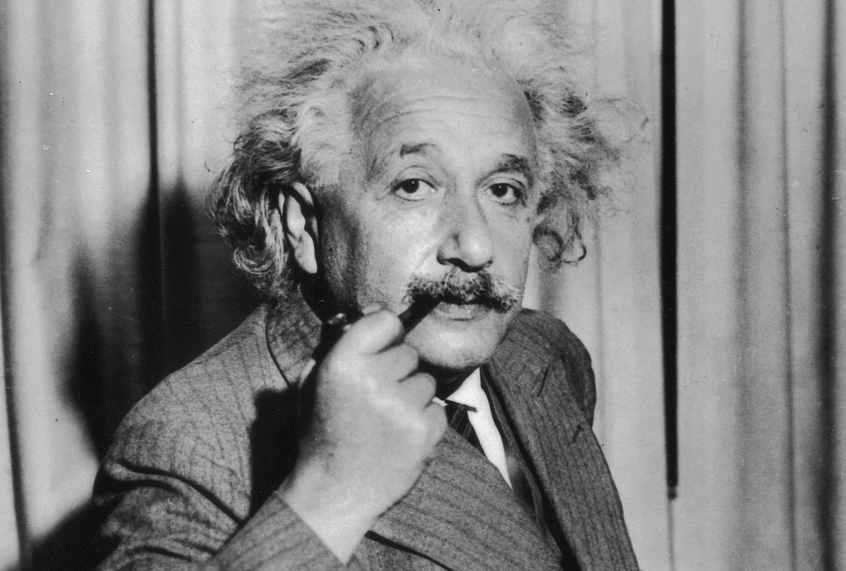

“The Travel Diaries of Albert Einstein,” which chronicle the renowned scientist’s travels in Asia in the 1920s, has been published in its first full English-language edition by Princeton University Press. As a spokesperson for the Press told the Guardian, “This is the first time Einstein’s travel diary will be made available to anyone who isn’t a serious Einstein scholar.”

The private diaries detailing Einstein’s five-and-a-half-month journey to the Far East and Middle East, including stops in Hong Kong, Singapore, China, Japan, Palestine, and Spain, were previously published in German. But now translated, “Entries also contain passages that reveal Einstein’s stereotyping of members of various nations and raise questions about his attitudes on race,” Princeton University Press writes. As the first volume in a planned series, this journal reveals significant contradictions to Einstein’s humanitarian and anti-racist legacy.

The writings, documented between Oct. 1922 and March 1923, feature the scientist’s meditations on science, philosophy, art, and politics, and the places and people he encountered on his voyage. “In China, the man who famously once described racism as ‘a disease of white people’ describes the ‘industrious, filthy, obtuse people’ he observes,” the Guardian reported. “He notes how the ‘Chinese don’t sit on benches while eating but squat like Europeans do when they relieve themselves out in the leafy woods. All this occurs quietly and demurely. Even the children are spiritless and look obtuse.'”

“I think a lot of comments strike us as pretty unpleasant – what he says about the Chinese in particular,” Ze’ev Rosenkranz, who edited and translated “The Travel Diaries,” told the Guardian. “They’re kind of in contrast to the public image of the great humanitarian icon. I think it’s quite a shock to read those and contrast them with his more public statements. They’re more off guard, he didn’t intend them for publication.”

The German-born Jewish scientist was known not just as a brilliant physicist, but as an advocate for human rights. According to the New York Times, Einstein once said in an interview, “Being a Jew myself, perhaps I can understand and empathize with how black people feel as victims of discrimination.”

The newly-translated journal shows the limitations of such empathy and humanism. Rosenkranz writes in “The Travel Diaries” that Einstein’s depiction of “other peoples are portrayed as being biologically inferior” is “a clear hallmark of racism.”

“It would be a pity if these Chinese supplant all other races. For the likes of us the mere thought is unspeakably dreary,” Einstein wrote. He described the Chinese nation as “herd-like” and “often more like automatons than people.” In other passages, Einstein writes, “I noticed how little difference there is between men and women; I don’t understand what kind of fatal attraction Chinese women possess which enthrals the corresponding men to such an extent that they are incapable of defending themselves against the formidable blessing of offspring.”

In Sri Lanka, formerly Ceylon, Einstein says of the locals, they “live in great filth and considerable stench at ground level” and they “do little, and need little. The simple economic cycle of life.”

The scientist is more favorable to the Japanese, though casts them as intellectually inferior. “Japanese unostentatious, decent, altogether very appealing,” Einstein writes, and then later, “Intellectual needs of this nation seem to be weaker than their artistic ones — natural disposition?”

Rosenkranz cautioned against dismissing Einstein’s racism as a product of the times. “That’s usually the reaction I get: ‘We have to understand, he was of the zeitgeist, part of the time,'” he told the Guardian. “But I think I tried here and there to give a broader context. There were other views out there, more tolerant views.”

In the introduction, Rosenkranz posits Einstein’s xenophobia and racism in the political climate of today. “In today’s world, in which the hatred of the other is so rampant in so many places around the world,” he writes. “It seems that even Einstein sometimes had a very hard time recognizing himself in the face of the other.”

While Einstein seemed to have evolved later in life, and less than 10 years after he documented some of his racist views of people and cultures around the world, he joined a committee to protest the injustice of the “Scottsboro Boys” trial, where nine black youths were falsely accused of raping two white women.

However, Einstein’s diaries lay bare how entrenched racism and xenophobia was in the United States and the Western world, whether one believed they were immune to such intolerance and prejudice or not. I don’t say this to excuse Einstein’s attitudes. This revelation must complicate Einstein’s legacy, just as Mahatma Ghandi’s anti-colonial work is inextricable from his proven anti-blackness and racism.

And critically, Rosenkranz is right. Once we examine this country’s history and even the leaders who were groundbreaking in some arenas and harmful in others, we can see the roots of the policy, rhetoric and attitudes of the administration today. Attorney general Jeff Sessions’ policy to prosecute anyone who crosses the U.S./Mexico border and separate immigrant children from their parents isn’t then “un-American,” as many liberals like to propose. It’s principally American, just as is the nonsensical police killings of unarmed black people and the mass incarceration of people of color.

As a country, and as does much of Europe — as Einstein’s diaries show — there is a vast record of believing in the inferiority of Native people, black and brown people, and foreigners who are not white. And by not facing this prejudice, by not untangling this racism, we see the continued dehumanization and lack of values for the lives of those same people today. So that’s why we can’t excuse Einstein, because America and Europe has been in the business of excusing racism for centuries.