The musical education of Lars Ulrich might have begun when he was 5 years old, and his professional tennis player father, along with the rest of the family, still lived in Denmark. Lars’ liberal, open-minded and music-obsessed parents took the precocious young boy to a free outdoor concert with the Rolling Stones. One can only speculate as to how much of the sleazy groove of “Honky Tonk Women” or the libidinous rage of “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” hardened like mortar into concrete within the mind of the future drummer. It wouldn’t take long for Ulrich to examine every note of Deep Purple’s live record, "Made in Japan," with surgical-style precision. The intensity of rock ‘n’ roll provided an escape for Ulrich, as he wrestled with the grueling training of tennis, and came to the painful realization that he would never measure up to the greatness of his father. The escape became the destination, and for decades, Lars has lived in the world of music. Even though legendary jazz saxophonist Dexter Gordon was his godfather, it’s been the world of hard and heavy music — music for people slow to take direction and quick to draw the middle finger.

Thousands of miles away, across an ocean and in another country, James Hetfield, the teenage son of strict Christian Scientist parents, while missing his father who abandoned him and the family, was finding peace and comfort in the assault and violence of tough guitar riffs and wailing vocals. He had a poster of Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler and Joe Perry on his wall, and his mother painted him into the frame, giving him support for his musical dreams and empowering him to envision himself sharing the stage with his rock heroes. He would allow “Train Kept a-Rollin’,” “Round and Round” and “Rats in the Cellar” to hypnotize him with visions of shaky fingers, banging heads and flashing lights. Hetfield, looking back on his childhood, calls himself a “really sad kid” living within the walls of familial pain, social exile and confused anguish. “Music cracked the shell,” he said. “It was my escape, therapy and savior.” The Rolling Stones sang, “I know it’s only rock ‘n’ roll, but I like it.” Hetfield not only liked it, but would later take a needle of permanent ink to his skin, and animate an angel delivering a single musical note through tongues of flame. An inscription, “Donum Dei” — Latin for “gift from God” — is underneath a tattoo of Saint Michael, a saint who had the unlikely ushers of Ozzy Osbourne, Bon Scott and Bruce Dickinson.

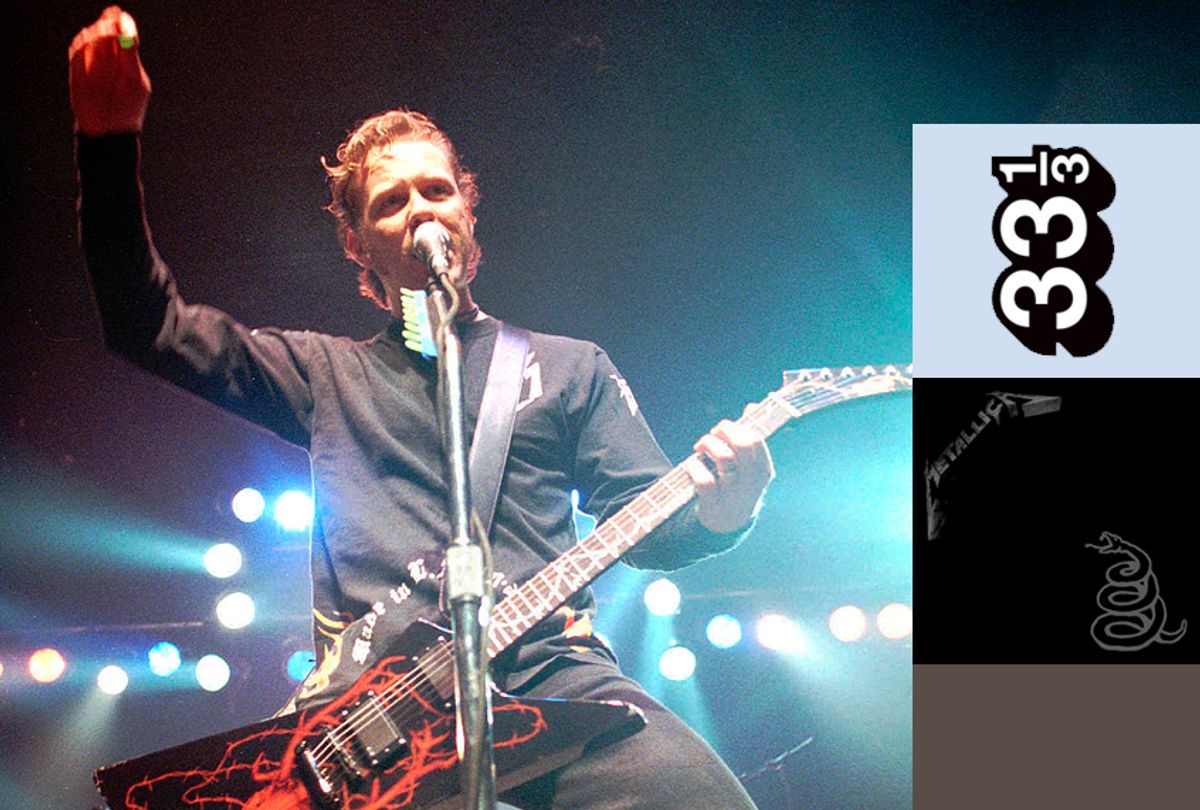

“Welcome to Hell” was the greeting that Venom — a heavy metal band from England — gave the world in 1981 with their influential album of the same name. The seizure-inducing speed of the guitar riffs and drum fills, the growling vocals, and the decidedly antisocial variety of Venom sank and swam into the veins of Hetfield and Ulrich. The tonic had begun to brew, and Metallica was ready to pour it down the throats of anyone who would pay the price of the cover. Metallica added the crucial ingredient of Americana to what Diamond Head, Venom, Motörhead and punk rock had already dropped in the barrel. The result was thrash, an extreme subgenre of heavy metal characterized by its fast tempo. Keith Richards once said that rock ‘n’ roll is just the blues played faster. Thrash is rock ‘n’ roll played with a rapidity to rival a race car. Mick Wall writes that 10 years earlier, Metallica might have sounded exactly like Deep Purple, and 10 years later they could have sounded like Alice In Chains. In 1983, no one was prepared for the band’s first album, "Kill ’Em All." Originally titled "Metal Up Your Ass," when record company executives and marketing directors of the small label Megaforce insisted on something tamer, Cliff Burton reacted with anger: “F**k them. Kill ’em all.” The stars were born. One of those stars was Kirk Hammett, a replacement for Dave Mustaine, whose volatility proved too much for Metallica’s stability. Hammett had already earned his stripes and scars with the metal band Exodus. In the Wild West of heavy metal, Metallica managed to replace Wyatt Earp with Doc Holliday.

READ MORE: What exactly lurks within the backward grooves of “Stairway to Heaven?”

“Thrash metal? OK, sounds cool,” Ulrich said, after reading what rock journalists called the in-your-face, ballsy and brawny brand of rock many of them credited Metallica with inventing. Within eight years, the band was already distancing itself from the term, and from what they viewed as its narrow associations. “When journalists call us thrash metal, we just see it as proof of their low intelligence,” Ulrich said in 1991, clearly no longer taking a casual attitude with categorization. Metallica’s resistance to the thrash label, which would only intensify as their career became more experimental, was also an attempt to establish distance between themselves and the other bands of what critics called “The Big Four”: Slayer, Megadeth and Anthrax.

Its appellation soon proved irrelevant. Reasonable minds should wish that the whole country could take after San Francisco, with its “ahead of the curve” embrace of punk rock, heavy metal and homosexuality, but America eventually limped its way to the finish line. In terms of metal, Metallica brought everyone to their house. They became ambassadors, but also royalty, managing to simultaneously represent and transcend the genre. "Kill ’Em All" killed everyone, and the sophomore album, "Ride the Lightning," would, like the capital punishment policy that inspired the story of its title track, take no prisoners and leave no survivors. The album gave Metallica new exposure to the world, considering they had left Megaforce for Elektra, a much bigger company with a reach that stretched much further into radio. From the band’s inception, there has always been two Metallicas. "Kill ’Em All" introduced one of them to the world — the devil-horned ramblers whose ultimate goal is to break the windows and wake up the corpses in the graveyard. Thrash loyalists loved it, and never wanted their heroes to change. "Ride the Lightning," with its metal grooves of “Fight Fire With Fire,” “For Whom the Bell Tolls” and the title track, gave them enough surge to recharge their batteries, but it also showed the second Metallica: the Metallica of “Fade to Black” — an existential ballad of depression with a similar structure to “Free Bird.” It was a song that broke one of the rules of heavy metal: no acoustic guitars. The derogation “sellout,” the most overused of all accusations, began to color heavy metal purist copy. “I played in a heavy metal band to get out of the box — the box that society tries to put you in,” James Hetfield said, “but then I learned that heavy metal can be the smallest box of them all.”

Shares