America does not conceive of itself as a country. More than a mere society, it is an Edenic paradise operating according to heavenly mandate. From Manifest Destiny to President Kennedy, and later Reagan’s co-optation of John Winthrop and the Sermon on the Mount, calling the United States a “shining city on a hill,” it is clear that American leaders and voters do not see their country as just another human setting – showcasing the triumphs and terrors of human fallibility — but a magical mass of divine favor.

President Obama attempted, with mixed results, to redefine American patriotism as an argument for its unique diversity, and its steady inclusion of immigrants, franchisement of minority ethnicities, and ecumenicism of religious devotion. The alternative civic-theology of President Obama enabled him to pander when he wrongly claimed that “only in America” was his story possible, but it also challenged the notion of America as perfect. Instead, America must strive to earn its blessings. Obama’s civil religion was similar to Catholicism in its insistence that “good works” are necessary for salvation.

In 1967, sociologist Robert Bellah first articulated the idea that Americans form a “civil religion” in praise of their own country, complete with rituals, saints and dogmatic doctrine. He also warned against the dangers of “self-idolization.” The idolatrous zeal of American life is largely a result of a Protestant application toward American civil religion. “By faith alone,” most Americans seem to indicate, can they achieve their American salvation.

President Donald Trump, along with his cultish supporters, does not view kneeling NFL players as protesters against what they perceive as injustice, but as heretics and infidels. When he instructed NFL team owners to “get that son-of-a-bitch off the field,” he was calling for the excommunication of congregants guilty of heresy.

Historians agree that the escalation of the American flag’s symbolic power occurred during the Civil War. During the war itself, and shortly after the Union’s victory, churches began flying the banner near the altar, with no feelings of contradiction from congregants, side-by-side with the cross. Craig M. Watts, minister and author, writes in his book “Bowing Toward Babylon: The Nationalistic Subversion of Christian Worship in America” that the major polity of America came to see “disrespect for the flag as not just boorish, but blasphemous.”

It would require approximately four seconds of thought to determine that the rage toward Colin Kaepernick, and other NFL protesters – whether one agrees with them or not – is irrational. It is a religious reaction not dissimilar to how a priest might respond to someone gargling communion wine.

The leadership style of Fox News prejudice meets spontaneous outburst of Donald Trump has reawakened American civil religion, pitting the devotees of a vulgar new iteration versus the “high church” establishment. A Trump aide recently told the Atlantic that his administration’s foreign policy doctrine is, “We’re America, bitch!” One imagines a 14-year-old having greater sophistication, but the crudity signals a religion drained of all content but its symbols.

Polls demonstrate that Americans have steadily lost faith in their society. Trump offers the cold comfort of reciting prayers for a patient in full death rattle. Meanwhile, Democrats combat the new jingoism with a patriotic appeal of their own: “We’re the real patriots.”

“Now more than ever,” to use the old slogan of Richard Nixon, Americans could use a healthy dose of darkness and despair in their treatment of American iconography. The politician who will express fundamental criticism of Americanism is a rare and brave breed. President Carter made a valiant effort in his prescient “Crisis of Confidence” address, and was nearly burnt at the stake.

It is American art that succeeds in challenging the simple and dangerous pompom waving for American empire.

Religion tells a story, but so does art. The only possibility for altering or widening the religious narration of American life — “shining city on a hill” — is through competition from an alternative story.

Andrew Wyeth earned the odd distinction of having critics call him both the “most overrated” and “most underrated” painter of the 20th century. His realism and regionalism provoked feelings of pride and pain; his art gave expression to the contradiction of the ordinary life in all of its glory, tragedy and, on most days, tedium.

With the aptly titled “Independence Day, 1961,” Wyeth paints an old black man sitting on his porch. A giant American flag billows in the opposite direction, its colors offering stark contrast to the muted tones of the ramshackle home. The man is a background figure, barely making an impression on the surface, unable to distinguish himself in the face of the flag.

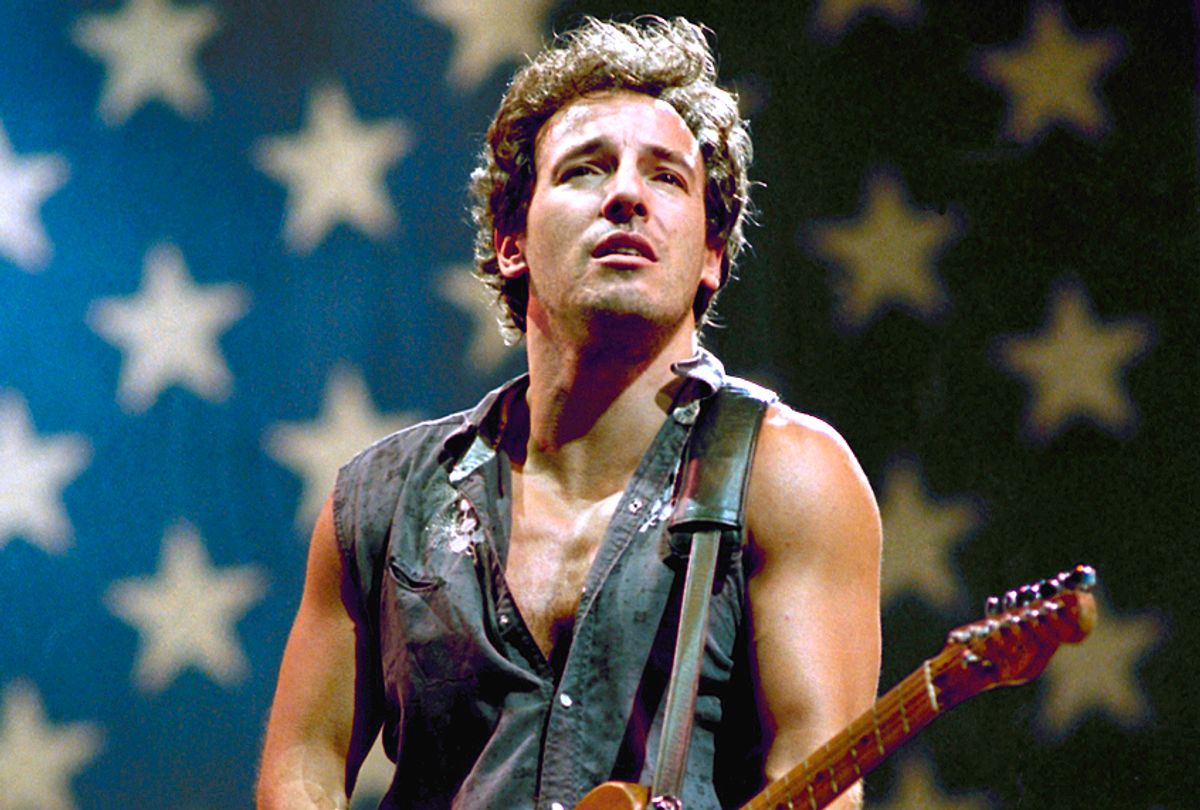

The Stars and Stripes acts as harassment to the man’s dreams and sightline — the equivalent of an empty platitude at a funeral. The Fourth of July, with all its celebratory fervor, is yet another meaningless ritual, ironically existing only to expose the hideous distance between fantasy and reality. Like the poor, bereaved, small-town Vietnam vet in Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA,” the cry of patriotism — the idea of national pride — serves only to taunt the subject over the security and comfort he is incapable of attaining.

Wyeth made his focus and emphasis rural America, while Edward Hopper — another realist — studied the aesthetic and spirit of the American city.

Beginning to paint in the early 20th century, just as the center of life was shifting from the provincial to the metropolitan, and from the agricultural to the industrial, Hopper captures the loneliness of progress. As America puffed out its chest, and became an economic powerhouse, paintings like “Automat,” “New York Movie” and, most famously, “Nighthawks” depict strangers without any hope for connection with one another. “Nighthawks” illustrates how the isolation of the people in Hopper’s paintings is often more palpable when they are in a crowd.

The race for commercial conquest, and the high-stakes achievement of America’s social hierarchy, overwhelm the individual, rendering him or her as merely decorative in the cold landscape of a country on the make.

Hopper exerted significant influence on the noir storytellers of American literature and film. Although the genre occasionally surrenders to camp, and it is easy to parody tough talk of “dicks” and “dames,” noir often succeeds in an exploration of the underside of winner-take-all capitalism.

The same erasure of humanity that Wyeth and Hopper could paint, Raymond Chandler was able to write. In the novel “The Little Sister,” Chandler’s recurring hero, Philip Marlowe, surveys Los Angeles in transformation. The lights fool the observer with their beauty. The reality is that LA. has a smell that has “gone stale” — “like a living room that had been closed too long.” California has become nothing more than the “department store state.”

“I ate dinner at a place near Thousand Oaks,” Marlowe tells his audience, “Bad but quick. Feed ‘em and throw ‘em out. Lots of business. We can’t bother with you sitting over your second cup of coffee, mister. You’re using money space. See those people there behind the rope? They want to eat. Anyway they think they have to. God knows why they want to eat here. They could do better home out of a can. They’re just restless. Like you. They have to get the car out and go somewhere. Sucker-bait for the racketeers that have taken over the restaurants. Here we go again. You’re not human tonight, Marlowe.”

If not human, what is Marlowe on a typical neon night? A customer? A walking appetite? An American?

Few writers have more movingly captured despair in the treatment of home than Joan Didion. In “Slouching Toward Bethlehem,” she writes that it is easy for people in the “golden land” of California to believe in the future, because “no one remembers the past.” Cities, and the people who inhabit them, “lose their character,” Didion prophesizes, when they trouble themselves with “self-doubt” over what they do not have, and self-inject the desire — the false need — for an unattainable more.

Only in a society of constant mobility and dreams of solitary victory, Didion writes, could Howard Hughes become a hero. The absence of a civilizing force of community in American neighborhoods creates depressed people and ever-vulnerable rebellions. Of the 1960s hippies, she writes:

We were seeing the desperate attempt of a handful of pathetically unequipped children to create a community in a social vacuum. Once we had seen these children, we could no longer overlook the vacuum, no longer pretend that the society’s atomization could be reversed. This was not a traditional generational rebellion. At some point between 1945 and 1967 we had somehow neglected to tell these children the rules of the game we happened to be playing. Maybe we had stopped believing in the rules ourselves, maybe we were having a failure of nerve about the game. Maybe there were just too few people around to do the telling. These were children who grew up cut loose from the web of cousins and great-aunts and family doctors and lifelong neighbors who had traditionally suggested and enforced society’s values. They are children who have moved around a lot, San Jose, Chula Vista, here. They are less in rebellion against the society than ignorant of it, able only to feed back certain of its most publicized self-doubts, Vietnam, Saran-Wrap, diet pills, the Bomb.

The current battle, insipid in most of its dimensions, over patriotism in America is a struggle to interpret the American flag, dream and idea. The winner of the honorific “patriot” is the party who will convince the majority of the country of its interpretation. Is it the Democratic Party fighting for a return to political normality and decency? Is it the kneeling protester attempting to broaden the meaning of the flag and National Anthem? Is it the president who rejects all complexity, and insists on uniform obedience to his narrow conception of citizenship and country?

The argument is important, but too shallow. It does not entertain the idea that, perhaps, something is fundamentally amiss with American culture, and as a consequence, patriotism will always fail to adequately and genuinely reflect its real essence.

A student from Croatia whom I befriended in college told me that upon her arrival in America, she was “startled” by the number of flags flying from porches, car antennas and buildings public and private. It reminded her of her own country just as it was about to break out into war — a war in which her father died. She also said that, although she had grown to love many elements of the United States, she would never raise a family here. She now teaches art to children in Florence, Italy.

That which most haunts American life, exactly like a ghost, is not something that people can view, hear or touch directly. It is a feeling, a mood — an intuitive knowledge of absence, rather than presence. Headlines of violence, escalating suicide rates, and sharp rises in loneliness sketch the edges of the American deficit in community, friendship and reciprocal respect and affection.

It is the artists who come closest in their grasp for definition. It is Didion’s California, Chandler’s inhumane restaurant, Hopper’s all-night diner and Wyeth’s front porch — the front porch where the big and bright flag fights for your attention, even your admiration, but you cannot take your eyes off the sad man in its shadow.

Shares