As the 2018 midterm elections approach, most Americans still view Donald Trump as an exceptional, if not unique, figure in American politics. From his most fervent supporters to his severest critics, most agree on that. So does the overwhelming majority of the political commentariat, who repeatedly characterize him as anomalous.

Not everyone agrees. Matt Grossmann and David Hopkins, authors of “Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats” (Salon review here), see relatively little change in how the parties are functioning, beneath the performative surface of Trump’s daily cable TV and social media drama.

Now a new book takes the argument even farther. In “The Great Alignment: Race, Party Transformation, and the Rise of Donald Trump,” Emory University political scientist Alan Abramowitz argues that Trump is the product of an ongoing multigenerational process that has reshaped American politics. In this view, Trump is a striking result of that process, but not a departure from what's been happening for some time — and will likely continue along similar lines after he's gone. The book’s focus on voters and the broader public differs from Grossmann and Hopkins’ party-focused analysis, but their long-term perspectives are complementary: Both see the GOP as a conservative party in the sense meant by William F. Buckley: It is “standing athwart history yelling 'Stop!'"

Abramowitz writes that "while Trump won the election by exploiting the deep divisions in American society, he did not create those divisions," and they won't go away regardless of what becomes of his presidency. He provides an abundance of compelling, detailed evidence, most of which has been lying around in plain sight — in the American National Election Survey (ANES), the results of presidential and congressional elections, etc. But as with the story about Columbus and the egg, you can stare at something for a very long time before someone else shows you the obvious.

Most fundamentally, Abramowitz argues that the New Deal coalition “based on three major pillars: the white South, the heavily unionized northern white working class, and northern white ethnics” was eroded by post-World War II changes that have transformed American society. Those resenting the changes have become increasingly Republican, those welcoming them, increasingly Democratic:

This transformation has included the civil rights revolution, the expansion of the regulatory and welfare state that was first created during the New Deal era, large-scale immigration from Latin America and Asia, the changing role of women, the changing structure of the American family, the women’s rights and gay rights movements, and changing religious beliefs and practices.

Three cleavages were most prominent in this process — race, culture and ideology — but they each had their own trajectories as well as interactions with the nation’s political geography.

For example, Abramowitz writes, “Results of national exit polls between 1976 and 2012 show that the racial realignment of the American party system took place in two phases.” The first, following the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, primarily entailed African-American voters registering in the South. “As late as 1992, Hispanics and Asian-Americans combined made up only 3 percent of the national electorate,” he notes. But after that, the impacts of immigration from Latin America and Asia produced a second wave of change, with different geographical impacts as well.

If the racial divide had its origins in the 1960s, the cultural divide first emerged in the 1970s, while the ideological divide widened most notably after that. Looking at four ANES questions about social welfare and the role of government, he writes, “The average correlation among the four social welfare questions increased from .29 in 1984 to .50 in 2012, while the average correlation between the social welfare issue questions and the ideology question increased from .25 in 1984 to .47 in 2012.”

This divide shows up strikingly in exit polls, as 74 percent of Obama voters favored a more active role for the government in solving social problems in 2012, as did 75 percent of Hillary Clinton voters in 2016, “while 84 percent of [Mitt] Romney voters thought the government was already doing too many things that should be left to private individuals or businesses,” as did 78 percent of Trump voters in 2016.

For all the nuance in the dynamics of how these divides widened, Abramowitz traces a broad pattern encompassing the whole: First came "de-alignment," as straight-party voting (79 percent in 1960) eroded (falling to 55 to 63 percent between 1972 and 1988), then realignment, as it rose again (to 81 percent in 2012) but with a twist: negative partisanship, which has been central to Trump’s emergence.

“In this book I explain how racial polarization and the rise of negative partisanship were crucial to the rise of Donald Trump,” Abramowitz told Salon. “They also explain his conduct in the White House, which can be described as governing by dividing.”

Compared to electoral patterns that held through 1990s, Abramowitz highlights three main characteristics: 1) “a close balance of support for the two major political parties,” producing “intense competition for control of Congress and the White House,” but 2) with “widespread one-party domination of elections at the state and local level,” and 3) “a very high degree of consistency” of electoral results “over time and across different types of races,” as state and local elections have become increasingly nationalized.

“These characteristics are closely related,” he argues. “All of them reflect the central underlying reality of American electoral politics: Today’s electorate is strongly partisan because it is deeply divided along racial, ideological, and cultural lines.” Trump is an extreme expression of this fact, but the underlying fact is that extremism has been brewing for quite some time. This was the first point Abramowitz addressed in an interview with Salon.

You write that Trump won by "exploiting the deep divisions in American society" but "did not create those divisions," and they won't go away regardless of what becomes of his presidency. What would you point to as the most striking evidence to get folks to pay attention who've been mesmerized by the Trump spectacle?

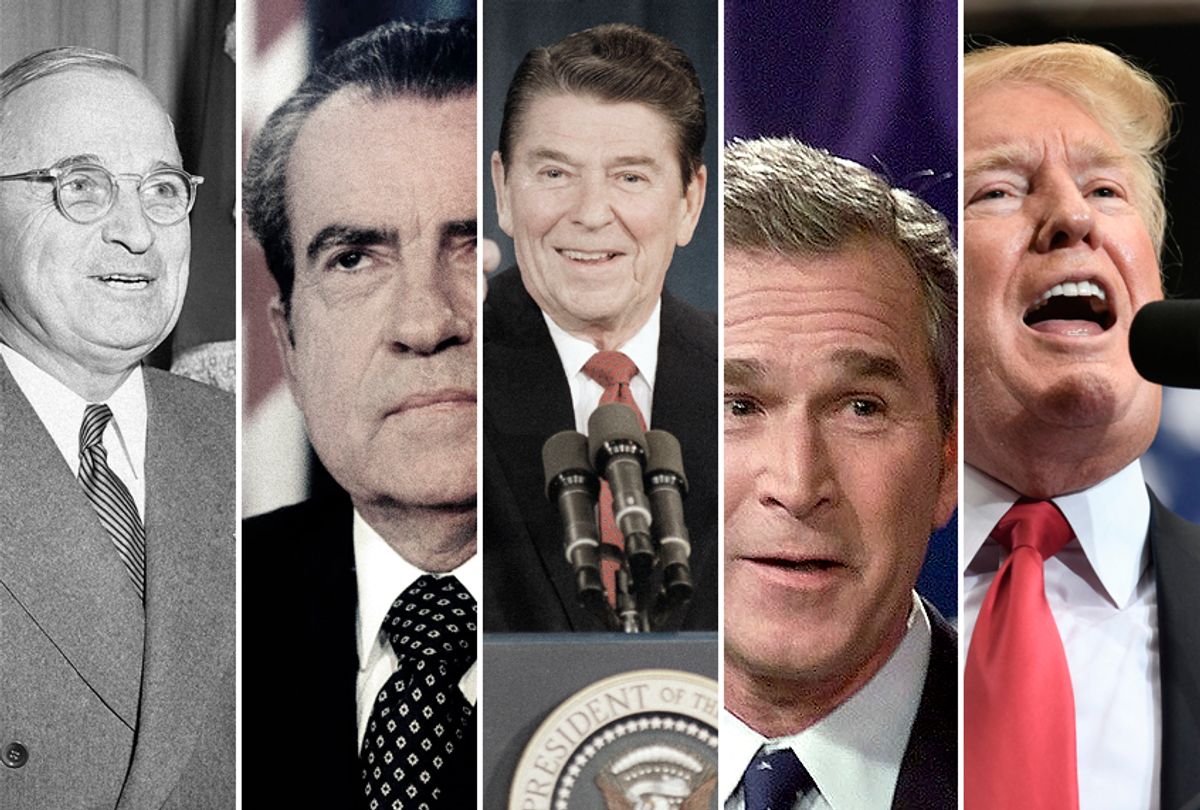

Trump is certainly different from previous Republican presidents and from current Republican leaders in Congress — different in style as well as, in certain areas like trade policy, in substance. But in many ways Trump is following in the footsteps of his predecessors.

For example, his attempts to exploit racial resentment among white working-class voters clearly follows in the footsteps of Nixon, Reagan and many other GOP leaders. I show that in response to these efforts as well as the growing diversity of the nation, there has been a sharp increase in racial resentment among Republican voters over the past 20 or 30 years — an increase that made it possible for Trump to exploit this issue in the 2016 Republican primaries.

Moreover, the ease with which so many current Republican elected officials and candidates have fallen in line with Trump’s agenda clearly reflects the divisions that exist today within the electorate and the deep support for key items in that agenda among the Republican base. Negative partisanship was crucial to Trump's victory and remains a key component of his messaging and support among Republican voters. Intense dislike and mistrust of Democrats in general and Hillary Clinton in particular has helped Trump to consolidate his support among Republican voters, despite reservations about his temperament and qualifications.

Your book is in some tension with others in the political science world. Most significantly with the older party-system literature that floundered over the question of what comes after the New Deal system, and with Stephen Skowronek's framework of "political time," largely focused on presidential decision-making. How do you see what you're saying in relation to those accounts?

The main difference I see with Skowronek and others you cite is that I see the actions and decisions of party leaders, including presidents, as secondary factors in the realignment of the parties. I see changes in American society and culture as the main drivers of party transformation, with presidents and other party leaders responding to those changes and exploiting the divisions they create within the electorate.

So, for example, I see growing racial and ethnic diversity and an increasingly secular culture, as well as changes in the structure of the media and rising education levels, as the key factors that have transformed the party system and shaped the behavior of candidates and elected officials. The actions of leaders matter, but I see those actions as constrained by the social and political environment in which they are operating.

If I were to summarize, I'd say that your book describes a non-linear progression driven by three main divides -- racial, cultural and ideological, with geography and interaction effects both playing important roles. How would you improve that description, and what would you cite as the most significant developments?

That’s a pretty good description of the argument of the book. One of the main things it sheds light on is the rise of negative partisanship. Overlapping divisions between the parties have led to the increasingly negative tone of our politics and especially the increasing fear and hatred of the opposing party and its leaders. This, in turn, has contributed to the rise of party loyalty and straight-ticket voting and the nationalization of electoral competition.

In your introduction you say that the book's central argument is that our "deep partisan divide ... is, fundamentally, a disagreement over the dramatic changes that have transformed American society and culture since the end of World War II.” Those who generally welcome the changes are aligned with the Democratic Party, those who don’t are aligned with the Republicans. At a superficial level, this is almost conventional wisdom, but its detailed implications are not nearly as well grasped. What's most important about this story?

I would say that the most important part of the story that is not widely grasped is that the divisions in American society shaping our politics today are mainly racial and cultural and not economic. That’s why so many white “have-nots” support Trump while so many well-educated “haves” are increasingly found in the Democratic camp. Education, not income, is the key divide because it correlates with racial and cultural attitudes.

You explain partisan polarization in terms of three main divides: racial, cultural and ideological, with the racial divide being the most important. What's most important about the trajectory of change they’ve gone through, and what's the most striking evidence to illuminate it?

I’d say what is most striking about the trajectory of change is that, at least with regard to the first two trends, they are driven by forces that seem likely to continue for some time. In the case of the racial divide, we know that the population, and therefore the electorate, will become increasingly diverse for decades. This is driven by the effects of differential fertility rates as well as immigration. As diversity increases, it is also almost inevitable that so will the negative reaction among a large segment of the white electorate.

With regard to the cultural divide, I see it likely to grow for some time due to the deep generational divide within the electorate. Young people in the U.S. are much less likely to be white and Christian than older people. So generational replacement will inevitably increase the proportion of the population who are non-Christian or secular in outlook, and this will almost certainly produce a negative reaction and pushback from those with more traditional beliefs. When it comes to ideology, I think the direction of polarization is less certain, although I don’t see it diminishing anytime soon. But that could depend more on factors such as economic conditions, which are much less predictable.

There's significant literature out there arguing that most voters aren't ideological. How would you reconcile the evidence in your book with those such as Donald Kinder and Nathan Kalmoe in “Neither Liberal Nor Conservative,” who make arguments downplaying the importance of ideology?

I have big disagreements with those who continue to downplay the role of ideology and the prevalence of ideological thinking in the electorate. A lot has changed since Converse wrote “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics.” The ideological divide between the parties is much sharper and the electorate is much better educated. There is incontrovertible evidence that voters today are far more ideological than they were in the '50s and '60s. The correlations among issue preferences and between issue preferences, and both ideological self-identification and party identification (and between ideological and party identification), are far stronger today than they used to be. This can be seen in ANES data but also in the Pew data on growing issue consistency and partisan polarization.

As for arguments about the relationship between affective polarization and issue polarization, they are in fact closely connected. It is precisely those voters who are most distant ideologically from the opposing party and its leaders who hold the most negative feelings toward the opposing party and its leaders. Issues and affect cannot be separated. We dislike the opposing party and its leaders mainly because we strongly disagree with its policies.

As I said earlier, geography plays an important role in your story. How would you summarize its impact, and what's the most significant evidence to support your description?

The political geography of the nation has shifted dramatically since the '50s and '60s, due directly to the ideological realignment of the parties. Sixty years ago, the geographic divisions within the country had little to do with policy and ideology. Today they are strongly correlated with policy and ideology. The most conservative geographic units (states, districts, counties) are the most Republican and the most liberal units are the most Democratic. Some of that reflects geographic self-sorting, but a lot of it reflects ideological realignment.

The title of your book suggests a static resting place, but the book itself is all about a continuing process. What are you actually saying about where we are as a country? How should people assimilate both the description of where we are and the fact that these processes are ongoing?

The process of realignment if dynamic and ongoing. That’s why I think it’s a mistake to think about a realigning election or event. American society continues to evolve, party leaders respond strategically, and the electorate in turn responds to both changes in society and culture and the actions of party leaders. There’s a constant interaction among these forces that results, over time, in the transformation of the electorate and the party system. Fifty years from now, I am sure the electorate and party system will look very different from today. For one thing, the Republican Party cannot survive indefinitely as a nationally competitive party if it continues to follow its current path of “doubling down” on aging, conservative white voters.

If you were to sum up, what are the three most important things about where American politics are today, as you describe them, that are commonly misunderstood?

That because of the rise of negative partisanship, we are in a new age of party loyalty and straight-ticket voting -- despite the negative feelings of many voters toward the parties and the popularity of the “independent label.” That the divisions within the electorate are primarily racial and cultural rather than economic. That tinkering with electoral rules will not have much impact on partisan polarization because its sources are deep divisions within the society.

Shares