Salon launched its Economy and Innovation category a month ago with a focus on how rapid technological change coupled with geo-political and social upheaval creates new economic dynamics. As part of that coverage, I will be interviewing one author each month. I'm looking for interesting and exciting books that address the issues and forces that are changing the landscape for everything and everybody; from the single individual to communities, companies, markets, governments, continents and even the planet — maybe even planets.

Our first subject: The Media.

Last month, Netflix surpassed Disney, becoming the most valuable media company on earth. Last week, AT&T and Time Warner’s historic court victory provided a milestone for AT&T as it looks to reposition itself in a rapidly changing media landscape and may well set off a heated round of industry mergers and acquisitions.

We’re in the midst of massive change in the media landscape, but to understand why these tectonic shifts are occurring now it is important to look at the corner of the media business that has been navigating disruption for years — advertising.

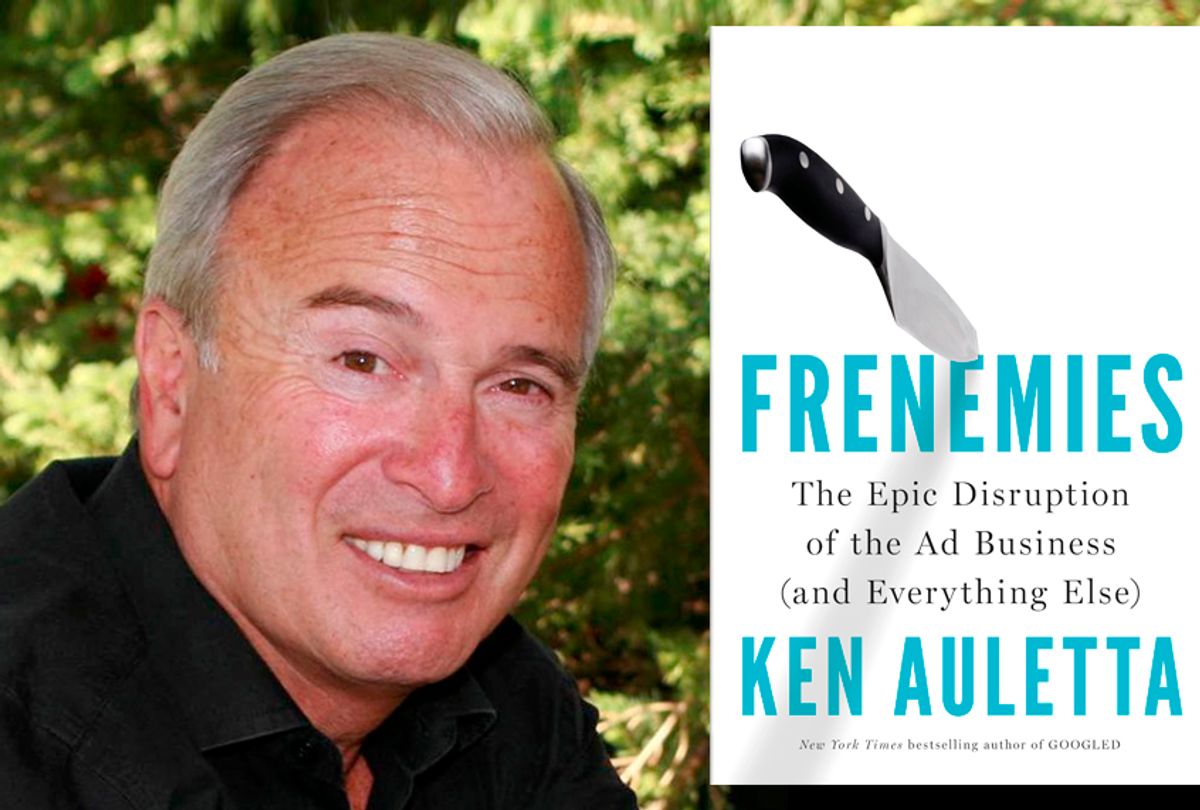

New Yorker writer Ken Auletta, who has covered every facet of the media business and hit the New York Times bestseller list with his 2009 book “Googled,” takes on the rapidly changing advertising industry in his newest book “Frenemies: The Epic Disruption of the Ad Business (and Everything Else).”

Auletta stopped by Salon's San Francisco headquarters last week for an honest, no-holds barred conversation with me about the state of the media industry and about change in general. We discuss how publishers and networks are responding to users’ low tolerance for ads and the ripple effects that behemoths like Facebook, Google, Amazon and Netflix create for all publishers. Auletta cautions that it’s a “scary time,” pointing out that it’s difficult for advertisers to have permanent allies, but also an exciting, unpredictable one on all sides. Being adaptive may be the only way to survive.

I first met Ken when I worked at Google during the research phase of his book and have been a fan of his writing for many years, beginning with “Three Blind Mice,” which covered the network television industry. His visit was occasioned by the release of his new book but also coincided with a historic week that included the ruling which cleared the way for AT&T’s merger with Time Warner and the end of net neutrality.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Ken, you have written books for three decades across many business areas, Wall Street to broadcast television, internet, why advertising and why now?

Well, I covered the media and I’ve written some books related to the media. When you think about following the money, where to get at [it] is you say, who subsidizes much of the media? It’s advertising. What do I know about advertising? Not very much. Why don’t I visit that plan and find out more about it and find out whether they are being disrupted? If they’re being disrupted, the consequences of that is that it radiates out and disrupts much of the media. I mean think about it, not just newspapers and magazines and apps, but 97 percent of Facebook’s revenues come from advertising, almost 90 percent of Google’s. If advertising falters . . . well, the ripple effects are profound.

Certainly, we see that here as a smaller website that is mostly dependent on advertising, and we’ve seen a lot of changes over the last couple of years on our side. I guess the question is, as you looked at the book and the research that you’ve done, what is your central thesis about advertising and the state of it? More importantly, how do you define a Frenemy?

Well, actually, Frenemy is central to answering your question. There are frenemies to advertisers and to agencies, particularly to agencies, and those frenemies would be people who are your friends but also your adversary or competitors. The publishing platforms that seek ads for their platforms are increasingly getting into the advertising business bypassing the agency and saying, “We can make money this way.” Native advertising is a perfect example of that and what you do here.

Yes. It’s less disruptive.

But the consulting companies, it used to be your accountants or your consultants who are increasingly saying, “Hey, this is an avenue we should go now. Advertising. We can make some money and that we have relationships." The C-Suite being the CEOs and COOs, et cetera. Then the PR agencies as business dries up with newspapers declining and say, “Hey, what is it with advertising, particularly in social networks?” They show advertising. They do it too. Clients (marketers) increasingly say they take stuff in house, and Google and Facebook have all this data and they bypass often times the agency [and] go directly to the client. Those are frenemies of the agencies that need those people but also compete with them.

But the biggest frenemy is the public because the public, particularly on the mobile phones, don’t want to be interrupted by shitty ads. I mean, if you think about it, that mobile phone is as personal to you as your wallet or a purse.

Suddenly, you are besieged by ads that feel like interruptions and you don’t like it. It eats up battery, pre-roll and banner ads are annoying, you can’t do a 30 second spot on it. So, what replaces that? That’s a really big question, and 20 percent of Americans have ad blockers on their cellphones; one-third of Western Europeans do. We look at the people who record programs in their DVRs, 55 percent of them according to Nielsen. They record a program and they watch it and they skip the ads. That’s profound change. Then you have places like Netflix where you don’t have to watch ads or HBO. It spoils people. They say, “I’m not going to put up with that crap anymore.” But that crap is what funds so much of the media and the news. So, it’s consequential.

It is consequential. You look at a world where advertising continues to be concentrated in a couple of players’ hands as every new dollar or 80 percent roughly, 90 percent [goes] to Google and Facebook.

Yeah, a little over three quarters of all digital dollars go to them. Now, it used to be that television was the largest recipient of ad dollars. Now it’s digital.

It’s digital. I think the question is, how long can that last before there’s fundamental tectonic shifts in businesses where they collapse. I mean, the investment in advertising is increasing overall still with GDP. Right?

Well, slower. But it’s increasing.

But there’s got to be a fundamental breaking point. Where do you see that happening?

Well, you could even make an argument that it is happening right now. I mean, if you look at some of the digital companies that were darlings two years ago, Buzzfeed, Vice, they’ve started laying off people. Who are their friend enemy? They’re looking at Google and Facebook that’s hiding more and more ad dollars from them. The question is, some of the digital upstarts that we have such high hopes for in terms of disseminating different information and then more choices. Well, some of them drop and die. I don’t know the answer to that, but that’s the question.

Well, some of the folks who have been around for a while, like one you brought up in the book, CBS, [have] been actually flourishing in this marketplace.

It’s interesting. [CEO of CBS] Les Moonves is a character in my book. The reason I chose CBS, I could’ve picked another network though, who arguably is the most successful modern television executive in the last 30 or 40 years. Can an old media company — a legacy company, a network like CBS — become new media? If you look at CBS, when I wrote a book in 1991 called "Three Blind Mice" about television networks, 100 percent of the revenues of CBS like NBC or ABC or Fox were from advertising. I said in that book in ’91, unless they get relief in the form of changes in some regulations by the government, they’re going to die because the advertising will be shifting elsewhere. What happened, the cable act was passed the year after my book came out. Not related, but it just happened. The new law gave networks retransmission consent where cable companies have to pay them to run their programs. Then they got “fin-syn” rules allowing them to own and make programs and sell them, a huge source of revenue.

Then Netflix and Apple and Amazon come on board, and they started selling programs to them. They’re frenemies, actually. Last year CBS got $250 million just with Netflix alone, right to the bottom line. It’s great. On the other hand, by selling their programs, they’re building up the competitor. Today, CBS went from 100 percent reliant on advertising to roughly 46 percent. That’s good for them, and they’re making more money today than they did 10 years ago. But in the long term, if advertising goes from 46 percent to 25 percent, they’re in trouble. If people continue to gravitate away from ad-sponsored programming and all those interruptions. They’re in trouble.

And there’s the other part of that. The 54 percent that you mentioned — which is the license fees particularly around cable and cable operators — are diminishing because of cord cutters. That leads me to my next point, which is really more on the news over the last few days with regards to AT&T and Time Warner, which you do mention in the book. So much has happened over the last three or four months in the media space, which we’ll get to and some other things too. But if you look at that merger at a time when AT&T controls a large amount of mobile market share plus DirecTV, is this a move that is going to ultimately help, or is this a call for help?

It is a call for help in a sense that they’re all spooked by Netflix and a little bit before that by Facebook, but particularly in television by Netflix and then Amazon. If you look at a place like Netflix, Netflix spends $8 billion a year on programming, which is four times what each of the networks spends on programming. That we can say, “Oh my God, how do we compete with them? They’re just going to open up a checkbook for all the talent and come direct to them." When you look at what Murdoch is doing by selling 21st Century Fox, he keeps the network. But he’s selling a manufacturing network, the studio that produces television programs.

At first I said, “Why the hell would he do this since he owns most of those programs and it generates income?” Now I think he [sold 21st Century Fox] because he realized he can’t compete with Netflix. So, scripted programming becomes too expensive. He can’t pay what the Netflixes or the Amazons and the Apples will be paying. He says, “I’ve got to get out of that business.” That means that by getting out, he sells off the network, what is [FOX] going to put on the network at night? He’s going to put on sports, he’s going to put on news and he’s going to put on reality or non-scripted programs and then live events of some kind.

What’s the consequence for other networks? If you’re the three other networks you’re saying, “Can I stay in the scripted business?”

Profound potential change there.

I think if you look at Murdoch's [sale of] 21st Century Fox and you look at the Time Warner sale to AT&T, that’s the underlying story there that [the traditional players are] spooked by Netflix. It’s defensive but it’s offensive in that you try to create a new business model.

Sure. Also, you talk about Netflix, but Amazon is right there doing the same thing.

Absolutely. Netflix is further advanced because they’ve been doing it longer and they have a bigger budget. Absolutely. They are looking at deep-pocketed competitors like Amazon, like Netflix, like Apple, like Google and YouTube, that they can’t manage that.

I want to talk a little bit about Facebook and what they have been going through with regards to privacy. I do believe Facebook has some vulnerabilities as a model. Certainly, privacy is adding fuel to that fire. How do you see Facebook over the next five years, given everything happening in privacy?

I think one of the big questions is, “What will government do?” If you watch the government officials who . . . the senators and the representatives who questioned [Mark] Zuckerberg, you say, “Oh my god, [these are] some illiterate people.” Zuckerberg can get away with saying, “I don’t know the answer to that. I’ll get back to you.”

He knows every answer to every question they ask. This is a knowledgeable guy. They didn’t know enough to challenge [Facebook]. I think it was Senator Orrin Hatch says, “How do you make your money?” I mean, it just takes your breath away where they ask them, do you feel like you’re a monopoly? He said, “Well, no, we have all these competitors.” We didn’t mention the four to eight competitors he owns. It was just crazy.

I look at them, and clearly they’re losing some [users], particularly younger people. Snapchat, which we thought would be a much more robust competitor, it’s not [there] yet . . . there’s a question [of] whether they’ll come forward. Also, Amazon is getting heavily into the advertising business and that’s breathing right down the neck of Google and Facebook. For instance, half of the people who do a search for a product, do it on Amazon not on Google. That’s a huge transformation. [Google is] being disrupted in their basic business by one of their peers.

I think the jury is out as to what happens to Facebook in five years. The dangers they have, one is privacy, huge danger. If the [United States] government decides to follow the 28 nations in Western Europe, basically they say you have to opt in to have access to my cookies. That would be huge and they would lose a lot of data. That will be big. Will that happen here? I don’t know. But the government could do other things, not just privacy. The government could regulate and pass laws that say, “Hey, you cannot buy potential competitors like Instagram."

Or they can go for the atom bomb and say, “We’re going to bring antitrust against you. You’re a monopoly.” Those are all questionable things. But those are the things government could do, right?

The second thing is . . . well, younger people kind of tire of it and say, “This is not a cool place to be anymore.” Or, “I’m worried about my privacy.” Or I like Snapchat better or Instagram better, which they own.

I do believe that these are dangers to Facebook. I’ll tell you one area that I hadn’t thought about until I actually read your book. That it was obvious — and I’m a little embarrassed to say it — but Facebook, by being a closed system, similar to China, as you mention from a country perspective, is not affected by ad blocking. They have actually an opportunity on that end if they’re able to get it right in terms of the consumer because every single ad is seen. The problem is they’re the only ones who can verify [an advertisement or a post]. I don’t know how long that lasts.

But the question then becomes the public. There’s a clamor that rises up from the public and says, “Hey, what’s going on here?” Including influential people in the public and the advertising community. If that happens, it could spur the government officials to act. Don’t forget, you will have informed government officials that they have people in the antitrust division of the Federal Communications Commission who know something and may start the [reform] campaign, may say, “Hey, we have to police these people, monitor this people.”

Well, actually, the ad I thought was interesting over the last couple of weeks that they [Facebook] have been running about how they’re changing.

One of the things that I think people miss is that . . . it’s very easy to think of a Mark Zuckerberg as a machine. But he’s a human being. He’s got two kids. He’s got a wife. He’s philanthropic. He hires people who have a sense of mission.

Suddenly, he’s being humiliated and shamed. What effect does that have on him? Is the ad just a contrivance or is it . . . is there something beyond that the way you say . . . he’s going to have [a] come-to-Jesus moment where he says, “I got to reform too.”

Yeah. It’s ultimately not what people say, it’s what they do. We’ll have to see what actually happens, right? Big news this week about net neutrality. It actually ended this week. You do mention it a little bit in the book. Obviously, it’s an issue that will go to the courts, and I don’t think there’ll be an immediate effect because [of] a lot of folks who probably are treading pretty lightly about it. We literally talked about how that affects advertising as much.

Well, I mean, clearly the Obama administration was pretty close to Silicon Valley powers that be. Net neutrality was something that had a lot of support. Much less support, obviously, in the Republican side of the aisle, as we’ve seen, because they rescinded it. Advertisers, I don’t think they took a really strong position, except they’re not in favor and wary of the digital giants and their power and the fact that they have data that they don’t share. But as long as I’m not going to pay more [for] my ads because in that neutrality on or off, I don’t have the same stake in it as Netflix or Google does. Do you agree with that?

I don’t. No. I think that ultimately . . . the problem that you have with net neutrality is that we have a show we run online that’s called "Salon Talks." If I were to call up anybody from Comcast [to complain] or anything like that, they don’t really care about us. If they don’t care about us, they don’t care about the advertisers who want to sponsor us. Ultimately, if advertisers feel that we’re not cared about, they’ll go to the places that their ads are going to be seen and cared about.

But [what] have you [gotten] rid [of] in that neutrality or have that neutrality? Does it affect with Comcast?

Well, I mean in terms of "do they favor that content that they own and operate?" It’s a question. I mean, if we don’t have an optimal viewing experience, users are very quick to turn you off.

If you follow your logic, that would argue that the advertiser has a stake and having more options, more platforms in which to have it done. They would oppose Comcast having control of the pipe and then for, potentially, where the traffic goes.

Sure.

It’s a natural tendency. The government, when they approved the Comcast acquisition of NBCUniversal, they put some restrictions on, which now come off, by the way, later this year. Basically, you say you cannot . . . you have to give good channel placement position to your news competitors like CNN and Bloomberg, et cetera, and you can’t favor your own content. But now that that structure is off Comcast, what happens?

Yeah. Listen, I think ultimately people on the business side will ask, “Is that good business or not good business to do that?” That’s probably why they’re treading lightly right now. But ultimately, I think nobody would be surprised what would end up happening. As you look at the people who are shaping this business, what is it that strikes you?

What I found . . . and I think this is common to businesses or institutions being disrupted, I found a level of anxiety that was intense. People who have had good careers and a good business every year regularly, suddenly are frightened. What has happened on the business? Are the walls going to come crumbling down? Out of that insecurity come sometimes rash behavior.

All those things are going on now. I found a palpable fear within the advertising marketing community, be it the agencies, holding companies, clients, platforms, publishers. Even to some extent the digital world. I mean, they’re insecure about the government today and what the government is going to do and the shame that is being visited upon them, and deservedly, too.

It’s really kind of enthralling to watch it and to watch how these people behave and what the moves they make are. If you follow my thesis about Frenemies, that makes them even more insecure because they don’t have permanent allies. I mean, they feel like Canada does with the U.S. today and Donald Trump.

It’s amazing. All right. My last question for you is, given that these businesses' dynamics are changing, if you are to write an additional chapter to Frenemies, what would it be?

Things happened in the last few months, and it’s not recorded in the book, including Zuckerberg appearing before Congress. My answer to that is this is the book about change. It’s a flowing, moving picture. If you read the book, you read a flowing moving picture. It’s not a series of still shots. Martin Sorrell [founder of WPP plc, the world's largest advertising and PR group] being gone doesn’t alter the nature of the book. It’s a book about change. I can’t think of a chapter right now; maybe a year from now or two years from now when we see what the government does on privacy.

Shares