If there was a silver lining for opponents of partisan gerrymandering who were disheartened by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions on Monday to punt two crucial cases for additional argument -- delaying the likelihood of fairer maps any time this decade — it arrived in an elegant concurrence by Justice Elena Kagan. There was also relief that the court left open the possibility of reining in the most extreme gerrymanders down the line.

Given the ticking clock, however, and a lost bipartisan opportunity to act — a Maryland case where Democrats obliterated a GOP congressional district, another from Wisconsin where Republicans entrenched control of the state assembly, using a buffet of statistical standards, reams of emails and draft maps declaring blatant partisan intent — optimism isn’t easy to find.

In the most important of the rulings, the court did not weigh in on the merits of the Wisconsin case. Instead, the justices unanimously kicked it back to the federal court. They determined that the Democratic voters who brought the lawsuit had not demonstrated a personal stake in the outcome or that their vote in their specific district had been diluted by a statewide map tilted to favor Republicans. Therefore, they lacked “standing” to sue.

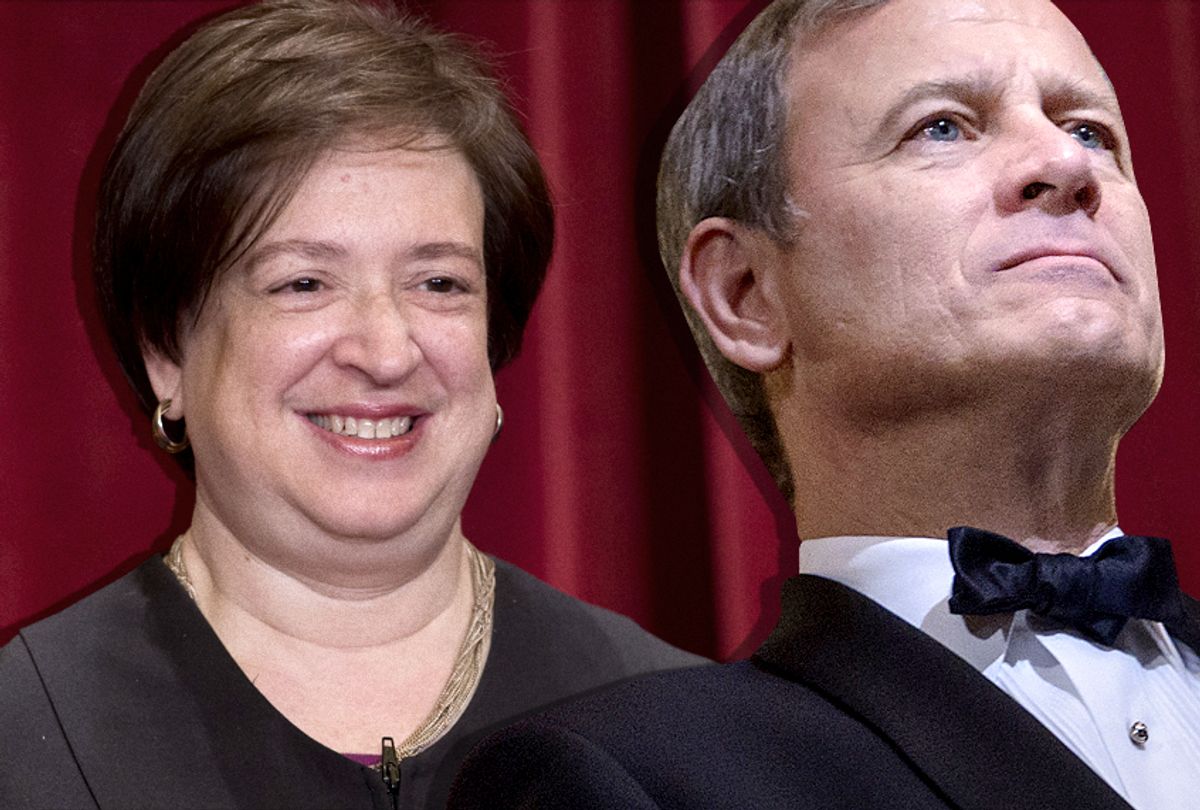

“A citizen’s interest in the overall composition of the legislature is embodied in his right to vote for his representative,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts, explaining the technical dodge. “The citizen’s abstract interest in policies adopted by the legislature … is a nonjusticiable ‘general interest common to all members of the public.’”

This is a curious definition of voter interest, and one that misunderstands the way a statewide map exists as a jigsaw puzzle of individual gerrymandered districts. It also fails to engage with how lethal today’s extreme gerrymanders have become, let alone how intently partisans weaponized redistricting during the 2010 cycle to entrench their own power and create decade-long advantages that survive even when their side wins many fewer votes.

After all, the statewide map invalidated as unconstitutional by the federal court produced a 60-39 GOP edge in 2012 -- despite 174,000 more votes for Democratic candidates statewide. They produced that result first by packing as many Democrats as possible into districts they won overwhelmingly, then scattering the others as diffusely as they could across the rest of the state.

Yes, the vote those citizens cast still counted toward the candidate of their choosing — but each district was "cracked and packed" to produce a statewide map that always favored Republicans. Behind closed doors, GOP operatives boasted that “the maps we pass will determine who’s here 10 years from now.” Their statistical analyses showed that Republicans would win at least a 54-45 edge with as little as 48 percent of the statewide vote. Democrats, meanwhile, would need 54 percent statewide to have a chance at a majority of seats.

Both sides found these seats so uncompetitive that 49 percent of all Wisconsin assembly seats lacked a major-party challenger in 2016. The entrenched assembly, meanwhile, gutted collective bargaining rights of state employees, enacted some of the strictest abortion guidelines in the country and passed a voter ID law so strict that some studies have suggested it kept more than 100,000 African-Americans from voting in 2016, perhaps delivering Donald Trump’s narrow 22,700-vote statewide margin.

Despite that debased state of democracy in Wisconsin, Roberts and the court used a standing technicality to decide that these voters had not been harmed within their individual districts. The state’s democracy is on fire, but the Court decided these citizens lacked the authority to call 911. They can try again later, once the blaze actually affects their home.

* * *

Kagan’s poetic concurrence, joined by the three other liberal justices, carried regret, pain and realpolitik. Partisan gerrymandering “violates the most fundamental of all democratic principles," she wrote. “Only the courts can do anything to remedy the problem, because gerrymanders benefit those who control the political branches,” she recognized. The practice “enables a party that happens to be in power at the right time to entrench itself there for a decade or more, no matter what the voters would prefer.” At its most extreme, it’s nothing less than “rigging elections.”

Nevertheless. Kagan still agreed wholeheartedly that the Wisconsin Democrats lacked standing to make a claim of voter dilution. However, she laid out a roadmap for lawyers to follow to make a First Amendment case where standing would not be at issue. Her path would not require a voter to prove their individual district was gerrymandered, because the entire claim would be statewide. Future reformers may well study this concurrence the same way that the last decade’s reformers scoured Justice Anthony Kennedy's opinion in the 2004 Vieth case — as the Rosetta Stone that deciphers decades of often confounding opinions sometimes at odds with themselves.

The standing problem, Kagan wrote, “may be readily fixable,” especially since “plaintiffs should have a mass of packing and cracking proof, which they can now also present in district-by-district form to support their standing.”

Kagan’s statewide approach had echoes of Kennedy’s interest in a First Amendment solution to partisan gerrymandering, as well as the case law on racial gerrymandering. “This Court has explicitly recognized the relevance of such statewide evidence in addressing racial gerrymandering claims of a district-specific nature,” and understands that drawing one set of lines affects the rest of the state. “The same should be true for partisan gerrymandering.”

She also seemed to invite political parties and other statewide organizations to file claims of their own: “By placing a state party at an enduring electoral disadvantage, the gerrymander weakens its capacity to perform all its functions,” she wrote, from fundraising to attracting good candidates to passing legislation. “If that is the essence of the harm alleged, then the standing analysis should differ from the one the Court applies.”

Kagan's concurrence ended with a warning and some blind hope. The 2010 cycle, she observed, produced “some of the worst partisan gerrymanders on record.” With ever-more sophisticated technology and precise data, “the 2020 cycle will only get worse.” Partisan gerrymandering will therefore be back before the Court — perhaps as soon as this fall in a case from North Carolina, where a lower court invalidated a congressional map that Republicans drew to a 10-3 advantage. “I am hopeful we will then step up to our responsibility to vindicate the Constitution against a contrary law."

* * *

But what, precisely, would be the basis for such hope?

The most immediate takeaway from these two decisions is that a unanimous court, once again, had no interest in helping settle the all-important debate over partisan gerrymandering.

Despite bipartisan amicus briefs from dozens of current and former members of Congress and governors that described how gerrymandering poisons the political process, the Supreme Court took a pass. Despite compelling briefs from political scientists and statisticians that demonstrated the historic turn for the worse during the 2010 cycle, the justices suggested reformers try again some other time. Despite an amicus brief from the law professor who helped Republicans assess the partisan impact of their maps, which practically pleaded for the justices not to allow politicians “free rein to violate associational and representational rights,” the Court wriggled uneasily. Despite a raft of social-science standards that allow courts to diagnose partisan gerrymanders as precisely as partisan operatives draw them, the Court pursed its lips and walked away.

Standing, after all, can be a fig leaf. It’s a savvy dodge that the Court can enlist when it serves its own purposes, as it has in recent debates over Obamacare, affirmative action in college admissions and many other cases. Roberts, who presented himself as an umpire in his confirmation hearings, did not want the Court calling balls and strikes over partisan maps for fear it would create “serious harm to the status and integrity of the decisions of this court in the eyes of the country.” (Insert your own eyeroll here.)

Indeed, it is easy to see Roberts’ handiwork throughout this decision. Step one, turn Kennedy’s Vieth concurrence against him during oral arguments, by suggesting the new statistical standards were vague, inconsistent “gobbledygook.” Then with the fifth vote secured, convince the liberals to make it unanimous and come along on standard with the promise of fighting another day. Roberts feared winning a 5-4 decision that would look political. The liberals feared dismissal or, worse, a finding of nonjusticiability.

The problem is that the Court remains in the same place as it was more than a decade ago after Vieth, with four liberals who want to craft a standard, four conservatives who do not, and a swing justice who can’t make up his mind. It would be easy to hail the Kagan roadmap as the path forward. But Kennedy, notably, did not sign onto it. There’s no reason to believe that roadmap applied to the North Carolina case or a reargued Wisconsin case would actually bring him along to yes.

Meanwhile, Kennedy could retire at any moment. There are liberal justices in questionable health. Republicans control the White House and the Senate. It’s hard to see how Kagan’s roadmap can attract that fifth yes under these conditions. Roberts, an artful dodger, understands all of this. He can afford to be patient. Time is not on the side of those who desperately believe the Court must step up and play a role. After all, when the Court failed to determine a standard in Vieth, it unleashed the partisan free-for-all of 2010-11 by making it clear to legislators that their power to gerrymander would go unchecked. Our last, best opportunity for a solution before 2020 hardball that will make even 2010 look like Little League may have just passed.

As a result, the message for partisans of both sides, already busy planning to spend hundreds of millions on redistricting-related races in 2018 and 2020, a fight certain to make our politics even nastier and brutish, is clear. Gerrymander all you want. When citizens complain, the courts will take so long to provide a remedy that you’ll get away with almost a decade of gains. Delay all you want: The Supreme Court’s got your back.

Shares