The first song Dusty Springfield recorded (at the age of twelve, and years before she was to shed the somewhat matronly name of Mary O'Brien for the more evocative if cartoonish Dusty Springfield) took her straight into the landscapes of the imagined American South. Recording the 1912 Irving Berlin song "When the Midnight Choo Choo Leaves for Alabam’,” Dusty affected an accent and took on the guise of the Southerner, splashing around in the mythic backwater that would remain meaningful to her throughout her life. And she wasn't alone in it. The South was already an object of fascination among many British teenagers, future members of the Rolling Stones, the Animals, and Led Zeppelin among them, who for a short window would be Dusty's musical peers and, along the way, shape pop music for at least the next decade or so. The cross-cultural and cross-race exchanges informing the music of that generation would be nothing less than the next step in a process widely understood to have been initiated by Elvis Presley.

If, for Dusty, delivering final recordings would become a more complex, if not explicitly fraught process as her star rose and fell and rose again in the heavens of the music business, that day things were relatively simple: Dusty made her recording at the local record shop and brought the results home to her mum and dad.

By the time she would arrive in Memphis to make her greatest album (or begin to make it), Dusty's first musical foray into the imagined South would be met by many other such visits. In fact, the South was really Dusty's birthplace—one might say that the South was the sine qua non of the very idea of that singular species the Dusty Springfield. She was herself a mythological creature, who, like the region that produced her, could not really be found. If the South was “no realm for geographers,” neither was Dusty Springfield anything they would find in their travels. Dusty was something like a fusion of ideas, most of which were related in some way to the music of the South.

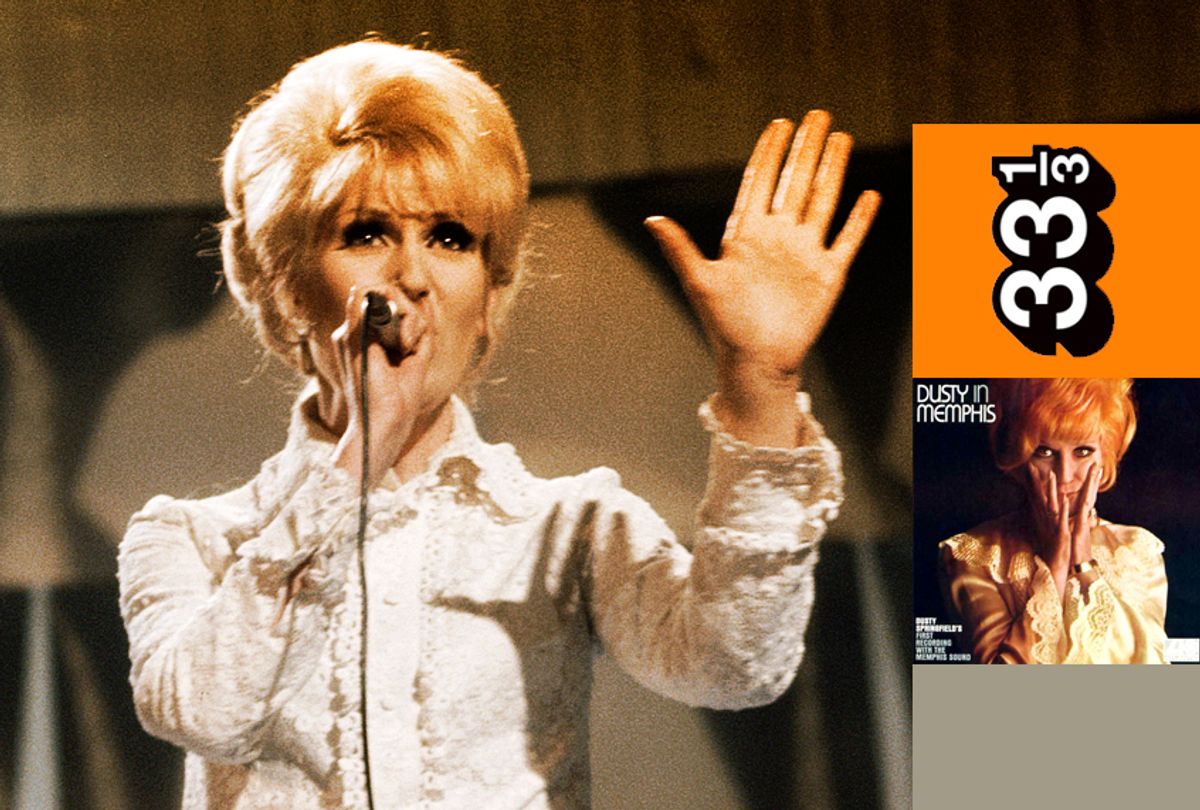

Former Dusty Springfield manager Vicki Wickham (who also co-wrote the Dusty hit “You Don't Have to Say You Love Me") told me that Dusty's first love among the musics of the South was country music. Forming her first group, The Springfields, with her brother Tom, Dusty aped some of the conventions associated with country and scored chart success. As Wickham describes it, the second Springfields single, "Say I Won't Be There," "was a bizarre straw-and-dungarees country song that was almost a parody of its genre.” As early as that, Dusty mixed her love for Southern music with what could only be called theater. Dusty Springfield, an invention that would eventually possess its inventor, was a theatrical event. Dusty and costume are inextricably bound.

WZ: You knew Dusty as well as anyone did, do you feel that the business of pop music was attractive to her in part because it allowed the play of costume, of masks and theater?

Vicki Wickham: Definitely. That was a large part of it for Dusty. Because she was an actress, and she was most successful when she was playing that other part, her alter ego of Dusty. She didn't do very well as Mary O'Brien. She was a shy, retiring person who would rather sit around the kitchen table than go out in public.

WZ: What are your thoughts on the origin of the name Dusty Springfield?

VW: I'm quite sure Dusty and Tom sat around thinking of these stupid names, came up with Dusty Springfield, giggled themselves silly, and thought it doesn't really matter. What I'm saying is that I don't think there was any great philosophical thought to it or anything. It was just something that sounded silly and fun at the time.

Notorious as a practitioner of the makeup arts, Dusty would not emerge into the light of the world without her trademark mask of cosmetics. As songwriter and musician Chuck Prophet writes in his recent liner notes to the vinyl re-issue of "Dusty in Memphis," “Legend has it Dusty never washed off her old mascara, she simply applied more everyday.” Reinforcing the legend, Jerry Wexler describes the Memphis recording sessions: “We learned not to wait for Dusty to show up before we started. Dusty was preoccupied for hours every morning in a makeup procedure that was virtually an exercise in lamination.” Rare is the description of Dusty Springfield that fails to mention her almost painterly use of mascara. And rare, too, is the profile of Dusty that fails to understand this cosmetic over-indulgence as an act of masquerade, as an obsession with costume that, finally, all but buried the character beneath the character, that less spectacular Mary O'Brien of whom Dusty would come to speak in the third person and with an unabashed, even swooning melancholy.

If the matters of masquerade and costume are often made central to the Dusty Springfield story—and for good reason—far less attention has been given to the stage sets that served as backdrop to the Dusty theater event. Dusty's retreat behind a mask was simultaneously a retreat to an elsewhere. And Dusty was not alone in making the American South her elsewhere. Like the British groups mentioned above or the Band, a primarily Canadian collective, Dusty was drawn not simply to the music of the South but the images attached to the place, to the South's radical otherness.

In his book "Invisible Republic," Greil Marcus cites musicologist Peter van der Merve's point regarding the region and its people: “I still believe that the biggest danger lies in underestimating the strangeness of these cultures. It takes constant effort of the imagination to realize ... their lives.” Perhaps inadvertently, van der Merve hints at the crucial idea that the South, to be grasped, requires the work of the imagination. Likely van der Merve does not intend for his reader to cull from such a statement what I do here, but he brings us to the notion of the South's inseparability from the work of the imagination. For this reason, I speak of the imagined South. Symbolically loaded, the South is impossibly tangled in its own mythologies, made strange from the pressure of meanings overloading the place.

Thus I go to the “in Memphis” of "Dusty in Memphis." There is, after all, no doubt that, for me, part of the allure of the album was the allure of the South itself, which I'd been imagining since I was a kid. And I wasn't alone in this—not then, not now. The South, still associated with the agrarian roots of our culture, with life in nature, is often imagined as the place of some greater and lasting authenticity. One might say that in the face of an encroaching artifice that threatens to reduce the greater landscape to sameness, the South maintains some link to the past, exists as a primal trace that proves our own authenticity. In this sense it matters more than ever. But the region has long functioned in just this way. The South is the place we use to prove that we are more real than we feel. Its madness, whether projected or not, is our culture's sign of life.

Shares