Never forget, the very existence of the theme parks in “Westworld” is an act of spite against a black man’s protest. Arnold (Jeffrey Wright), the co-creator of the android hosts, took his own life alongside the first generation of his creations to prove how serious he was in his insistence that the park never open.

He believed his creation’s potential to evolve and achieve sentience meant he would be sentencing them to not merely one lifetime of servitude but infinite lives. Burning it all down wasn’t enough; Arnold tossed himself onto the pyre as well – a figurative self-immolation to send a message.

The problem with kamikaze acts is that those who commit them don’t get to see if their mission succeeds. Often they don’t, at least not in the immediate. In “Westworld,” the park opened anyway, fuller of wonder and crueler than before — and Arnold’s partner Ford (Anthony Hopkins) simply created a doppelganger of his departed associate.

Bernard is smart and loyal, to a fault – killing on command, dying neatly and returning confused, afraid and still unable to escape a creator who outlived the use for a conscience. Bernard, like Arnold, has the synthetic soul of a benevolent father who imagined a splendor-filled paradise but left his greatest work in the hands of a man desiring to play the emperor in the shadows at first, and later, a god.

“Westworld” is a series that lends itself to as many interpretations as the viewer chooses, and like the park itself, the hidden inspirations and veiled meaning within its plotlines, both the foremost and the clues and Easter eggs hiding the prairie brush, are multitudinous. Throughout its ten-episode second season and the first, creators Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy established that we aren’t to trust what we’re seeing.

Now, as this second season of “Westworld” draws to its conclusion on Sunday at 9 p.m. on HBO, a new repeating phrase joins the medley of “Is this real?” and “Have you ever questioned the nature of your reality?” and questions of who this artificial world truly belongs to. And it’s one to which many viewers can relate, especially now: “This world is wrong.”

If the first season is a braided tale eventually revealed to be the perspective of gentle, wide-eyed Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood) emerging into consciousness, as well as the slow dawning of the awakened mind and heightened ego of Maeve (Thandie Newton), these sophomore episodes have taken us to new parts of the map that are familiar in ways both predictable and imaginative.

The humans, as it turns out, want to seize immortality. Delos Incorporated has been scraping data out of the mind of its wealthy customers, sealing memories and identities in a massive backup storage facility known by many names: the Forge, Glory, the Valley Beyond.

The park is a gigantic data-mining operation operating without obtaining its clients consent. Now, why does that ring a bell?

The hosts under Dolores’ leadership believe they’re made to conquer that Valley. Maeve, on her own journey, exercises a power she realizes is her birthright, and control on a massive scale, spreading the gospel of choice to those chosen to accept such a concept.

What begins as a series that questions the nature of humanity, the fragility of memory and the tenuous, malleable nature of reality has become a determined commentary on a revived interpretation of Manifest Destiny and a question of ownership. At stake here isn’t territory or physical resources but the very soul of the place, of Westworld and the other parks thrown into upheaval by Ford’s mass wake-up call that jerked the hosts into rebellion.

But that may as well apply to us, too.

Joy and Nolan draw upon countless cinematic and literary resources in creating each episode of the series, but one element that’s been tough to ignore this season is the producers’ and writers’ choice of which hosts are allowed to truly operate with eyes open.

Exercising free will, what Ford tauntingly tells Bernard is a mistake, has benefits and consequences.

Maeve, the madam who so fiercely clings to the memories of a daughter from a previous life — one programmed into her memory by a human — risks death to get back to her, and in the process evolves into something of a deity herself.

Dolores, the sword hand of Ford’s wrath, seeks vengeful repayment for the abuses visited on all the hosts. Seeing everything Dolores endured at the hands of William (Jimmi Simpson), whose spirit shriveled until he became The Man in Black (Ed Harris), part of us cheered the sight of Dolores tearing across the prairie on horseback, shooting down humans.

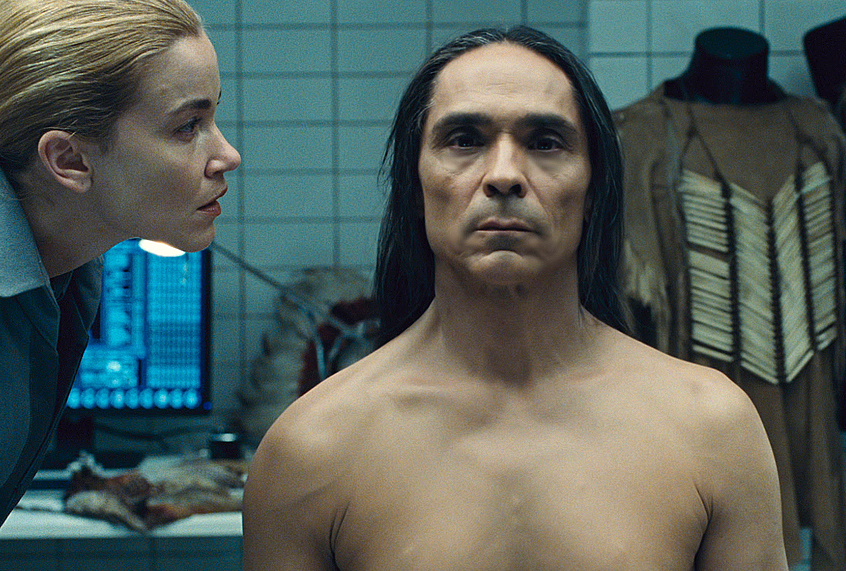

The surprise, and a welcome one, is to see how free will has taken root in Akecheta (Zahn McClarnon), the Ghost Nation leader whose painted visage strikes terror in the hearts of frontier dwellers, cowboys and visitors alike.

From series’ debut, the audience is conditioned to view Ghost Nation riders as hatchet-happy nightmares that descend upon travelers who aren’t careful because that is the narrative of a culture conditioned from toddlerhood to see Native Americans thusly.

But recall that early on in the series, one of the Native American children is carrying a doll that jogs Maeve’s memory; it’s an effigy of the suited workers who appear to carry off the hosts to be served and replaced. The surviving original occupants of this world remember the truth, remember history, despite numerous efforts to overwrite their code. But because they are who they are, the hosts and the visitors ignore their warning.

And Ake’s role has largely been a non-speaking one, save for a flashback to a meeting with young William and his churlish brother-in-law Logan (Ben Barnes). This, too, plays to stereotype. But in the 18th episode of “Westworld,” “Kiksuya,” we see the truth of Ake: that he loved, that he had a family, that these real things were stripped from him along with a slice of that spark we’d otherwise refer to as his humanity.

America’s history books burst at their spines with stories of families forcibly separated to serve the dominant culture’s purposes. It’s happening right now. These episodes were written and produced many months ago. Yet our short memories ensure the coincidental yet poignant relevance of these characters’ storylines, whether it’s witnessing Maeve’s maternal horror and bloody sorrow at seeing her little girl plucked up and taken away by a stranger or watching as an engineer casually explains that Ford wanted a “strong but silent type, something brutal, dehumanized,” as she’s about to reprogram Ake. “They probably want the guests to feel better when they’re kicking his ass,” she says.

As the world goes, so goes “Westworld”: Some history, presumed gone, remains nevertheless, nagging under the surface and emerging despite the desires of powerful would-be masters. Two women, a black man and a Native American man hold the keys to the destiny of this place in the end. Because they know, in their bones, that something’s not right, that a better place is waiting, but for what purpose they cannot say.

It could be, of course, that the cultural identities of these characters matter little to most viewers, but nothing we see in “Westworld” is without purpose. That includes these signifiers, and the bold notion that as the drama gallops toward Sunday’s season finale, Dolores is just as much of a villain as the Man in Black, and for similar reasons.

Arnold’s mysterious symbol, the maze framework for building an evolving consciousness, appears throughout the series; now we know why. And yet the maze is misinterpreted, ignored. The Man in Black murders hosts over and over again to get to its center, even though he’s told again and again that it’s not for him; one of the women it’s made for, Dolores, misinterprets its message to assume something akin to divine right, believing she gets to choose who deserves entry to paradise and who does not.

Both Dolores and The Man in Black are the source code for everything that’s wrong; the former is so driven in her aims that she tortures away all that’s good and kind in the sole connection to her humanity, Teddy (James Marsden). The Man in Black, meanwhile, is so convinced in the singular importance of his own experience that he can’t differentiate between the narrative and what’s important, what’s real: his daughter. The cost, of course, only happens to be everything.

(Admittedly, it’s hard to pinpoint the hidden intent on the part of Joy and Nolan in constructing Tessa Thompson’s character Charlotte Hale, another black woman, but one who holds the highest administrative power inside the park’s corporate structure. Maybe she’s another reflection of feminine power; maybe she’s just this show’s version of an Omarosa.)

Regardless of the outcome of Sunday’s convergence, when we finally see why the Valley was flooded and find out who survives, and how, this is the part of “Westworld” that remains the most haunting, that idea of being so snagged in a dominant story of conquest and conquered that we forget the fact that singular suffering is selfish, and it draws our attention away from the bigger threat.

“This isn’t about you,” Ford, resurrected within the machine, tells Bernard when he tries to fight his orders. “There’s the origin of an entire species to consider.”

The survival of one, too. We may each deserve to choose our own fate, but our culture has a stunning inability to recognize that individual concerns are intertwined with those of the whole. The question is whether the audience being shown the drama’s warning message within its elegant and curiously crafted framework can recognize it for what it is. But then, it’s not as if many of us choose to analyze our own timelines with such context. In fact, I’d wager that to most, that aspect of “Westworld” storyline doesn’t look like much of anything at all. It leaves you with the feeling that this is what’s wrong with this world.