Humanity has dispatched humans and/or robots to explore many different alien worlds in our solar system, yet the number of large bodies from which we have brought samples back to Earth numbers only three: the Moon, Comet 81/P, and asteroid 25143 Itokawa. This is partly because of expense: a one-way robot mission is far less complicated than a two-way one, and there are all kinds of unknown variables that come into play in sample return missions. Now, as a Japanese space probe approaches the Ryugu asteroid, there's a chance that number will go up to four.

After a long 186.4 million-mile journey — one which took about three and half years — a spacecraft named Hayabusa-2 has successfully rendezvoused with a unique asteroid named Ryugu.

“From this point, we are planning to conduct exploratory activities in the vicinity of the asteroid, including scientific observation of asteroid Ryugu and surveying the asteroid for sample collection,” Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency JAXA confirmed in a press release on Wednesday.

Following its arrival, the next step is to prepare to survey the asteroid for sample collections. Hayabusa-2 is expected to bring rocks and dust to Earth from the carbonaceous asteroid.

This alone is an exciting prospect to many in the asteroid-studying community.

“One of the great aspects of Hayabusa-2 is that it will be a sample-return, so it has to interact with the surface of that object,” Alan Fitzsimmons, an astronomer in the QUB Astrophysics Research Centre, explained in a press conference hosted by the B612 Foundation on Thursday. “In the past we have only done that with a different type of asteroid.”

Those past missions include NASA’s NEAR Shoemaker, which collected samples from an asteroid named Eros in 2001. (Unlike Hayabusa-2, NEAR Shoemaker was not a sample return mission, however.) Remote studies of those samples, according to NASA, have since provided scientists with a better understanding of how asteroids like Eros are linked to meteorite samples found on Earth.

Eros is an S-type asteroid — short for silicaceous asteroid — which means it orbits the sun, and is mostly composed of nickel-iron rock. Ryugu is thought to be different, a C-type or carbonaceous asteroid— in other words, containing largely carbon. While most asteroids, according to Fitzsimmons, are believed to be C-type, it is important for scientists to continue to learn about all different types of asteroids.

“But that doesn’t guarantee that when we want to deflect or closely inspect an asteroid in the future that it will be silicate, it could well be a carbonaceous asteroid... and so we are going to learn a lot, first of all, just from the interaction,” he said, referring to the interaction between Hayabusa-2 and Ryugu.

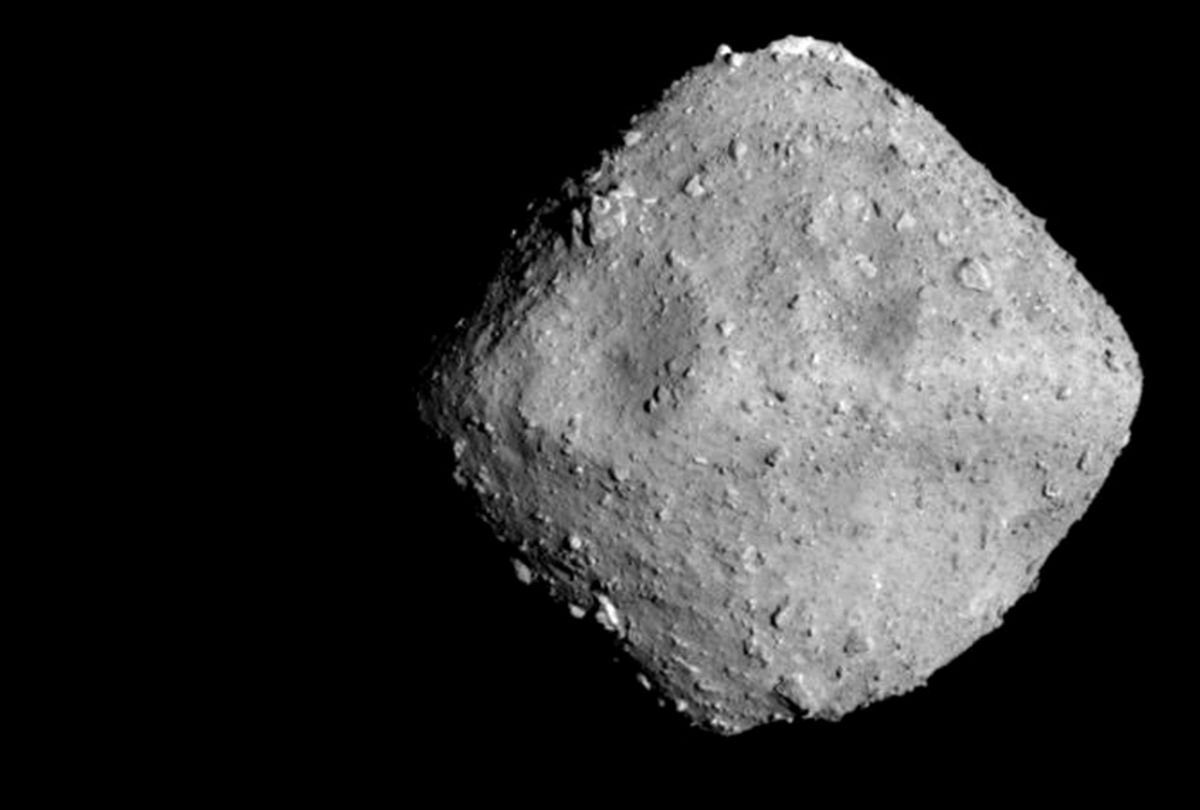

The advancements made in such little time during this mission are remarkable. As JAXA explains on its information page, not too long ago Ryugu was merely a featureless dot on the spacecraft's Star Tracker. It was not until earlier this week that scientists got a close look at the asteroid, and were surprised by its shape.

“From a distance, Ryugu initially appeared round, then gradually turned into a square before becoming a beautiful shape similar to fluorite, known as the 'firefly stone' in Japanese,” project manager Yuichi Tsuda said in a 25 June statement.

"This form of Ryugu is scientifically surprising, and also poses a few engineering challenges," the statement added, referring specifically to the challenge of landing on a low-mass and therefore low-gravity object like Ryugu.

Fitzsimmons noted that the spacecraft's arrival at Ryugu has already yielded important scientific data.

“We are seeing on its surface a fairly complex terrain,” he told Salon. “It is something we did somewhat anticipate given that many of these objects of this size are rubble-pile asteroids... they are not a single cohesive body that you might expect to see if you are a fan of 'Star Wars' or science fiction movies.”

Still, it will be some time before the samples arrive in an Earth lab. In late 2019, Hayabusa-2 will start its one-year journey back to Earth — universe-willing — with its precious rock samples in hand.

Shares