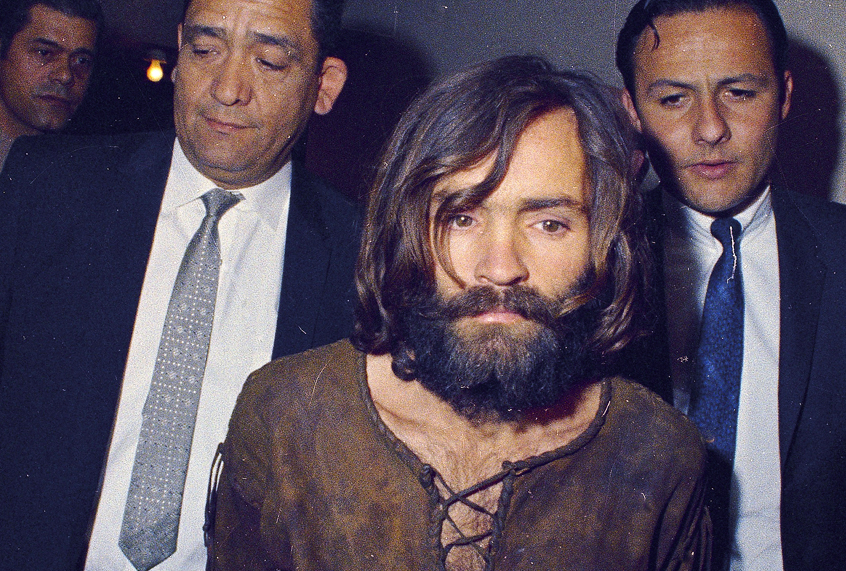

The year 2019 will mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Tate-LaBianca murders that made Charles Manson a household name, and the man and his Family are still everywhere. In 2016 they were on network television with the return of Season Two of David Duchovny’s “Aquarius” to NBC’s schedule. They were at the center of Emma Cline’s debut novel, “The Girls,” which was prominently reviewed all over the mainstream press, hitting the New York Times Best Seller list within two weeks of publication. They were in the news in the developing story of the most recent parole hearing of Family member Leslie Van Houten. As 2017 began, Manson’s staying power was undimmed: there was a major survey of the art of Raymond Pettibon in New York featuring numerous Manson-inspired works, a heavily promoted Family documentary on ABC, early word of a new film project based on the meeting of Manson and television host Tom Snyder in 1981, and online whispers suggesting that the year might also finally bring us the long-rumored indie film project, “Manson Girls.” Well-promoted teasers about Manson-related movies from prestigious film directors Quentin Tarantino and Mary Harron also crossed our screens.

During 2016 and early 2017, Manson’s presence — at once frightful and comic — took on added resonance in the context of Donald Trump’s campaign for, and ascension to, the presidency of the United States. Given that Manson has served for decades as a kind of shorthand for charismatic pathology, it would have been hard to resist Manson/Trump juxtapositions. So, during the campaign multiple Internet rumors about Manson’s putative endorsement of the candidate circulated; more than a few compared Trump to the cult leader with respect to the power he held over his followers. In the early days of 2017, when Manson was rushed to the hospital for an undisclosed health emergency, Andy Borowitz and other comic writers suggested that now the president-elect would have to take the cult leader’s name off his shortlist to fill the Supreme Court seat of Antonin Scalia. Others noted similarly that when they saw Manson’s name trending on social media after his health scare they at first assumed it was because Trump must have named him to a cabinet position. Most efficient of all was a widely circulated GIF that simply put video footage of Trump and Manson side by side so that viewers could observe and draw conclusions from the similarities in their exaggerated facial expressions.

The past few years have been relatively strong for Manson-related cultural chatter but this is really a matter only of degree. Since August 1969, when a few members of the Family spent two nights killing seven residents of Los Angeles in what generally travels under the banner of the “Tate-LaBianca murders,” the Family has never slipped from the American radar for long. We have rarely been able to talk about “the sixties” without Manson and his “girls” somehow entering the discussion; many of our most important cultural conversations about teenagers, about sexuality, drugs, music, California in the sixties, and yes, about family, mention the Manson Family in one way or another.

And then the man died. Manson’s death in November 2017 is not likely to change much about how he has operated in, and on, the American consciousness. The coverage of his demise at eighty -three did not show any indication that the volume was being turned down: the sober paper of record, the New York Times, headed its obituary with a phrase that described Manson as the “Wild-Eyed Leader of a Murderous Crew.” Twitter was briefly aflame with the news-and was largely taken up with baby boomers instructing millennials why they should not be commemorating the event with “RIP Charles Manson.” As the year ended, Manson appeared near the top of almost every list of major celebrity deaths, and rarely was he treated with anything other than the ritual horror that has so often attended mention of his name. The Times’s predictably detailed coverage repeated at some length the narrative first proposed by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi at the 1970s trial, and then later codified in his 1974 book “Helter Skelter,” that suggested Manson directed his “murderous crew” to kill seven people over two nights in August 1969 as part of his evil plan to incite a race war.

Bugliosi worked hard at the trial of Manson to develop this story and never stopped working on it up until his own death in 2015. This “Helter Skelter” story has become much more important as a cultural script, meant to explain a good deal about the chaos of the American 1960s even if it could not necessarily hold water as a full or coherent explanation for Manson’s actions. Our continued investment in Manson has not waned and suggests that we all are taking on the role played by the talent manager Col. Tom Parker who, upon the death of Elvis Presley, was asked what he planned to do: “Why, go right on managing him.” There is every indication that we plan to go right on managing Manson, who shows no signs of becoming any less useful to us in death than he has been as a living presence for the past fifty years or so.

While Manson and the Family gained notoriety in connections with the killings of August 9 and 10, 1969, it was creepy crawling, more than murder, that was their emblematic crime. I understand that Manson and the Family are most well-known for the murders of 1969, and that these murders provide an abundance of salacious, terrifying, and bizarre details: the writing in blood on the wall, the stunning dialogue reported from Cielo Drive, the post-murder snacks and showers — there is a generation’s worth of film, fiction, and song built from the basic elements of the crimes. But I am not interested in the crime itself: I am much more interested in how the overall presence of the Family has been impossible to shake after its dark fame was established. The murders were bounded events. They happened, investigations and trials ensued, the convicted were incarcerated. But the creepy crawl never ended: Manson continues to make challenges to our sense of family, to our legal and judicial systems, to our minds. The Family, in short, has been central to the construction of American identity from the last days of the 1960s through our own time.

What the Family meant by “creepy crawling” was at once simple and profoundly upsetting. Leaving their communal home at Spahn Ranch in the San Fernando Valley, the Family would light out for private homes. Once inside, the Family members would not harm the sleeping family members. Instead, they would rearrange some of the furniture. That’s all. Stealing was sometimes part of the agenda, especially toward the end, but it was not the raison d’etre. No dead bodies, no blood on the wall. Just the bare minimum of evidence that the sanctity of the private home had been breached-that the Family had paid a visit to this family.

The significant cultural legacy of the Manson Family is embodied in the creepy crawl. Our understanding of Manson and the Family’s place in our national history has been too often hampered by cliche, above all that they represented the “end of the sixties,” which is tempting, and convenient: after all, the murders took place in August 1969 and Manson and his confederates were indicted that December. It was the end of the 1960s. But that only gets us so far. There is little question that the Manson Family has held sway (to borrow the title of Zachary Lazar’s Manson-inspired novel, which Lazar borrowed from the Rolling Stones’ own end-of-the-sixties song of the same name) over our minds for almost half a century now. The power of the Manson Family goes well beyond matters of body count and even beyond the manifestly gruesome details of those two August nights.

The Family appears so many places, communicating so many different claims about who we are, what we fear, and how we got here, that is has long been necessary to develop a key to crack the Manson Code. This requires a kind of detective work that Vincent Bugliosi was not inclined or trained to do. True crime books are mostly organized around the same question: whodunit? But what if we stop focusing on the “who” (we more or less know the answer to that question) and start paying attention to the “it”? What exactly is it that we are accusing Manson and the Family of having done? Murder, of course, but what else? Misreading song lyrics? Eating garbage? Having too much sex? Doing too many drugs? Loving one another?

It is important to keep in mind that the sheer fact of our obsessive repetition of Manson lore is a big part of the story I am after here. When it comes to Manson, it is not just that we ritually retell the facts of the case, or name-check Manson and his minions in song, story, film, and so on; we use “Manson” repeatedly as a historical shortcut, a quick and efficient way to tell much larger stories. Here’s an example. Joan Didion was one of the many journalists to find gold in the Manson case. Relatively early on she cozied up to Linda Kasabian who had turned state’s evidence and according to some reports was planning to write a book about the former “Manson girl.” Didion did not write that book, but she did write about the murders at length in The White Album (and I imagine some of you reading this could probably chant this along with me): “Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, ended at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brush fire through the community, and in a sense this is true. The tension broke that day. The paranoia was fulfilled.” I have been researching my book on Manson and the Family for some years, and I only wish I had kept count of how many times I came upon these words of Didion, repeated as gospel; without an accurate count, the best I can offer at this point is an indefinite hyperbolic numeral along the lines of “umpteen” or a “gazillion.”

Charles Manson and members of his Family were convicted in 1971 for crimes connected to seven murders committed in August 1969. From the time Manson and his followers were arrested up until today, the Family has also regularly been prosecuted for killing the counterculture, the “free” love movement, hitchhiking, the freak scene, and the 1960s as a whole. Along with the doomed concert sponsored by the Rolling Stone at the Altamont Freeway in California just a few days after the decisive break in solving the case, Manson quickly became a punchline and an epitaph. The spectacular murders of August 9 and 10, 1969, five at the Cielo Drive home shared by actor Sharon Tate and director Roman Polanski, and then two at the Waverly Drive home of Rosemary and Leno LaBianca the next night, contributed an enormous amount of energy to a story that got told over and over again, in many different forms, about how this was a tragic but necessary reboot: the counterculture had gone “too far” and these murders were somehow the natural result of too much something- with drugs and sex the most commonly cited villains.

Insofar as we have developed a collective belief in a meaningful and recognizable stretch of time that we agree to call “the sixties,” there is a surprising consensus that Manson somehow helped to end the era. The stunning amount of investment that has been made in this construction should remind us above all that plenty of people were really eager to shut the door not just on Manson but on all the hippies, Yippies, and freaks he came to stand for. For sheer destruction of human life, the Tate-LaBianca murders do not rise to the level of the daily horrors inflicted at the same time by American forces in Vietnam, or the string of race riots that marked the decade, but we do not have the same tendency to claim that these “killed the sixties.” The uncomfortable truth is that Manson was quickly converted into a weapon used to discipline the unruly generation in which he had immersed himself.

Joan Didion’s words have contributed a great deal of energy to this cultural effort. This apocalyptic tale-telling had a clear case to make about the promiscuous cultural mixing that had been rife in the previous half decade. As the story goes, this was all bound to lead to a crack-up. Didion has not carried the torch by herself, of course. The end-of-the-sixties rhetoric has become a standard feature in voice-over documentary narration (what Twitter regulars have come to refer to more generally as Ron Howard voice), in journalistic feature stories, and in the work of plenty of professional scholars such as Todd Gitlin, who frames his reading of the Manson affair as belonging in the “realm of the demonic.” There was a sense of doom in the air,” Gitlin informs us. “The culture,” Gitlin explains, was “full of intimations of ending.”

I don’t want to invest too much energy prosecuting a case against Didion, Gitlin, and others who want to use the Manson moment as an occasion to shut the door on a number of the most ambitious movements and social experiments of the 1960s. There are plenty of Latin phrases you could throw at these forces of simplification and generalization (post hoc ergo propter hoc, for example), but what I care most about is how they participate in building a cult(ure) of Manson. The creepy crawls were short-term and episodic, but the whole point is that even locking up a number of the key members of the Family has not done much to expel Manson from our midst. From Didion to Bugliosi to the dozens, if not hundreds, of artists who have kept him present, the creepy crawl abides. Manson’s Family have proven to be the (uninvited) guests who never leave.

There is a film clip in the AP archive dated 1971 (and now on YouTube) that shows five women associated with Manson literally crawling through the streets of Los Angeles. This is, as the AP record puts it, a “stunt”–the young women are making sure that the people of Los Angeles know that even with their sisters and brothers behind bars, the creepy crawl lives on. It is pretty fascinating to track the reactions of the people they encounter. First a young man walks by, content with the apple he is eating and not paying much attention to the crawling women: this is Los Angeles and who knows what else he has seen on his walk. Then, after the camera shows us that they are crossing the intersection against the “Don’t Walk” sign, we see the Family women pass a very square-looking white woman in matching sweater and skirt, white handbag slung over her forearm. This woman makes a slightly alarmed move to give these crawlers a wide berth, but then cannot help but turn back in order to get another look at the fascinating sight. At the same time, two youngish looking African Americans pass the women but appear not to even notice them. On the next block a fairly hip group of young white people comes out of an office building to watch the show. For the most part they are having a good time, except for one woman who is nervously chewing on her fingers. Two construction workers continue to do their work. A woman with a brown paper sack catches up to the crawlers and bends down to feed one of them; it is not clear if she is part of the stunt or not. The final significant figure, who I hope received an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in some alternate universe, appears in the final seconds of the clip. He is white and middle-aged. He is mostly bald and his pants are hiked up a little bit higher than the national average. When we first see him he is pointing with alarm at the group–it seems possible he is trying to enlist somebody else to help him rectify the situation. But then we see him again as he crosses the street to get closer to the action: with one of the most eloquent shrugs in film history, this Angeleno has under-gone a change of attitude. Our furniture is being rearranged, his shrug seems to say, and I guess there is not a damn thing we can do about it. Over the course of the 1970s it got more and more difficult to shrug the Family off. In our own time we continue to wrestle with what the new arrangement of furniture means.