A big part of Donald Trump’s strategy to whip up racist hysteria against immigrants is straight-up lying. Last weekend, for instance, Trump breathlessly declared on Twitter that he has “watched ICE liberate towns from the grasp of MS-13,” a lie so ridiculously over the top it would be funny if so many people didn’t believe it. Unfortunately, Trump knows his constant stream of tall tales about immigrant gangs controlling American cities will gain traction, no matter how often they’re debunked in the media. Research indicates that the public is drastically misinformed about the nature of immigration in the 21st century, making many Americans easy marks for Trump’s propaganda.

This week, a new working paper from Harvard economists was published in the National Bureau of Economic Research that illustrates how dire the situation really is. The researchers surveyed people in six countries — Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden and the U.S. — and found that native-born people in all six nations had ideas about immigration that were drastically out of step with statistical realities and often much closer to negative stereotypes propagated by the right.

“We had an intuition that people would be off” in their perceptions of immigrants, researcher Stefanie Stantcheva told Salon. That intuition, she said, “turned out to be more right than we thought.”

There are a lot of ugly stereotypes that people have about immigrants, such as believing that they’re lazy or have criminal tendencies. The researchers chose to focus on a handful of these myths that “can be checked against reality,” as Stantcheva put it. These include how many immigrants there actually are, where they come from and what their economic circumstances are really like.

“An overwhelming majority in all countries have really skewed perceptions about immigrants,” Stantcheva said.

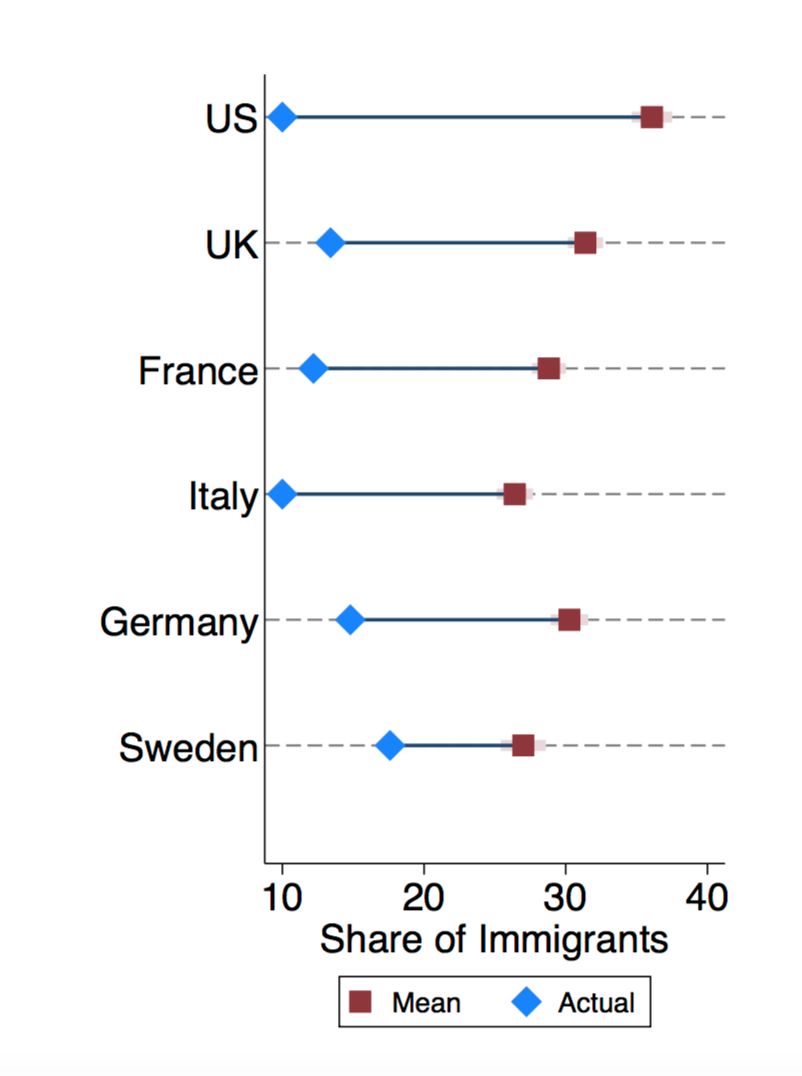

For instance, in the United States, native-born citizens drastically overestimated how many immigrants there are. Native-born Americans estimated that 36 percent of the population were legal immigrants, when the reality is around 10 percent. These wild exaggerations of reality were seen in most countries, though the Swedish were the closest to reality in their estimates. This chart, courtesy of the Harvard researchers, shows the gap, with the blue dot representing reality and the red dot representing what respondents guessed on average.

Americans were also bad at guessing where immigrants originally came from or what their religious background is. For instance, less than 1 percent of immigrants to the United States are from North Africa, but respondents estimated it was closer to 8.5 percent. About 4 percent of immigrants come from the Middle East, but survey respondents put the number closer to 12 percent. Only about 10 percent of immigrants are Muslim, but Americans guessed it was over 22 percent. And while more than 60 percent of immigrants are Christian, respondents estimated the number to be less than 40 percent.

Even more disturbing, perhaps, were the misperceptions people had about the economic circumstances of immigrants. Only 5.5 percent of immigrants are unemployed and 13.6 percent live in poverty, but native-born Americans put the numbers at 26 percent and 35 percent, respectively.

While all categories of Americans had distorted views of immigration, some people’s views were notably more distorted than others. Conservatives, unsurprisingly, had more distorted views than liberals. Low-skilled workers who work in industries that employ a large number of immigrants also had more distorted views. Interestingly, however, high-skilled workers who also had a large share of immigrant colleagues — such as computer programmers — while still off in their estimates, were closer to the mark.

One intriguing variable, researchers discovered, was personal relationships.

“If you have regular contact with an immigrant, if you have friends or acquaintances who are immigrants, you tend to have more accurate perceptions along all these dimensions,” Stantcheva said.

One important thing to consider with this paper, however, is that the section measuring who has the most and least accurate views of immigrants only measures correlation, not causation. For instance, Stantcheva said, it’s possible that knowing immigrants causes people to have a better understanding of immigrant realities, or it could be that people who have more accurate views of immigrants “may just decide to get to know more immigrants.”

While the first part of the paper only describes correlations, the second part of the paper does get into experimental territory. To measure how people’s feelings about immigrants affected their attitudes toward income redistribution, researchers split respondents into two groups. One group got the questions about immigration before they were asked questions about their views on the social safety net and income inequality. For others, the order was reversed.

By asking people about their views on immigration, Stantcheva said, they “are made to think about immigrants.” The result was such people became stingier, even if they generally held more liberal views.

“Those who were shown the immigration questions first are more averse to redistribution, believe inequality is less of a serious problem, and donate less to charity,” the study authors write.

The charity results — in which respondents were told they were enrolled in a lottery to win $1,000 and asked what percentage they would like to donate to charity — was particularly interesting. Many people who defend hostility to immigration argue that it’s not about racism but rather about a national responsibility to put native-born citizens ahead of foreigners when it comes to things like jobs or welfare benefits. Charitable spending, which is about generosity and not duty, presumably should not be impacted by such arguments. Yet people did reduce their (hypothetical) charitable donations when primed to think about immigration, and those who held more negative views of immigrants reduced their donations the most.

This research is certainly dispiriting to those who are frustrated by Trump’s anti-immigration demagoguery and who want the United States and other western countries to become more welcoming to immigrants.

“These results suggest that much of the political debate about immigration takes place in a world of misinformation,” the study authors conclude. “Citizens and voters have distorted views about the number, the origin, and the characteristics of immigrants.”

But there is a possible opportunity here. While many avid right-wingers who believe false things about immigrants are unlikely to be talked out of those views, which they cling to out of a fervent desire to believe, this research suggests that a large number of Americans and Europeans might be reachable by education campaigns. Stronger public education efforts from pro-immigration activists and journalists about the reality of immigration could go a long way to calming public fears and increasing tolerance.

We’re already seeing this in the aftermath of Trump’s family separation policies. As people learn more about refugees and start to see them as they are — hard-working families, often seeking to escape terrible violence — stereotypes are challenged by sympathetic realities. The large crowds that turned out to support Central American refugees over the weekend was a testament to how much power education can have when it comes to changing people’s minds on the reality of immigration.