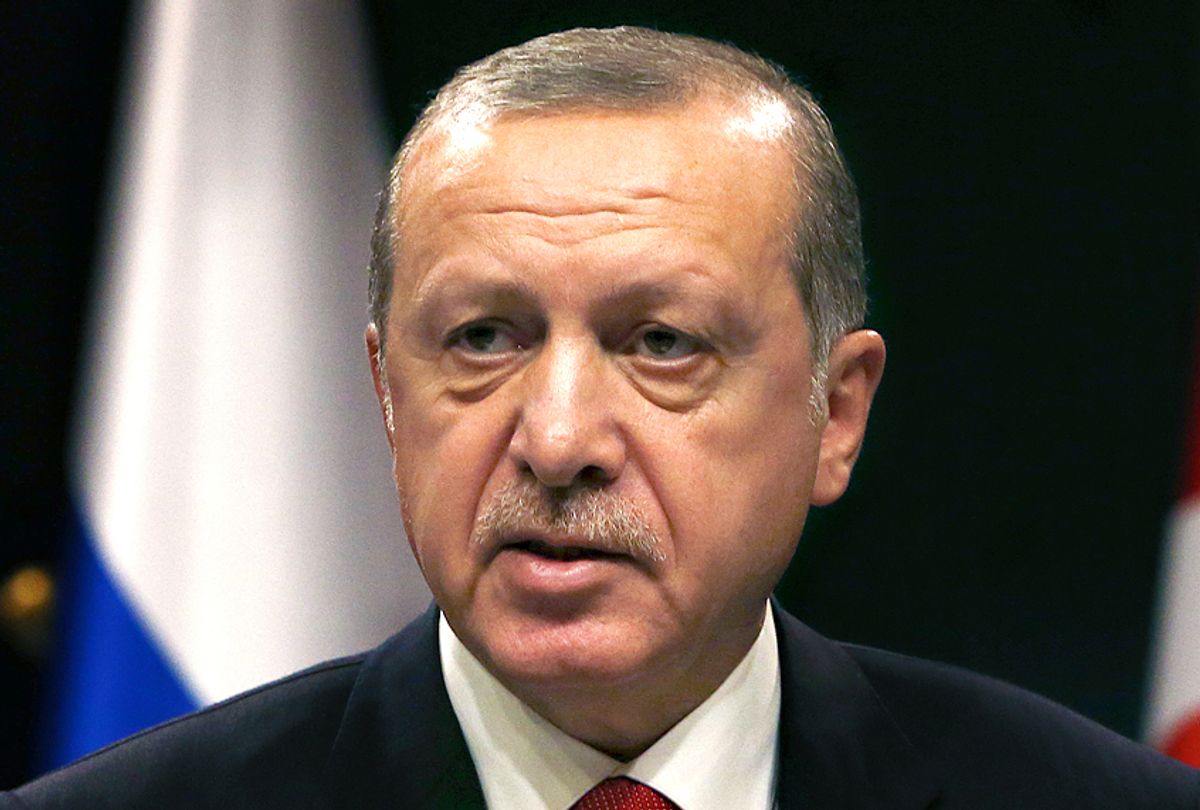

Turkey, NATO’s second-largest member, is bracing for further violence and chaos following the victory of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in an election that cemented his near-dictatorial powers.

Celebratory gunfire rang across the streets of Istanbul and other Turkish cities early on Monday after his victory, with about 52.5 percent of votes, was announced (observers said fraud was minimal). However, his promises of economic prosperity and stability ring hollow, experts say.

And fears of further violence and crackdowns in the country are growing.

“Things will get worse before it gets better,” Cenk Sidar of Sidar Global Advisors — a strategic advisory firm based in Washington, DC — told WhoWhatWhy. “[The] Turkish economy is still under major pressure due to political risk, private sector [indebtedness] and decreasing international competitiveness. Also there is no clear sign that political tension and polarization in the country will be ending.”

Following the election, and a constitutional referendum last year which takes full effect now, Erdogan, who describes himself as a moderate Islamist, has become Turkey’s first executive president; he will preside over the official transition to a presidential republic. It is the triumph of years of efforts: to force through his vision, he has cracked down on civil liberties, thrown his opponents in jail by the tens of thousands, and started a controversial foreign intervention as well as reignited a closely-linked domestic insurgency. The once-prospering economy, over which he has presided for more than 15 years, is close to its knees.

Despite widespread fears of vote rigging and reports of a few incidents, the election was relatively free of fraud, if hardly fair, observers say. The official results largely match figures provided by independent observers, Gurkan Ozturan, a journalist and the executive manager of the Dokuz8 independent citizen journalism news agency, told WhoWhatWhy. Dokuz8 is one of the last news platforms outside the government’s grip in Turkey.

However, Erdogan’s rivals received almost no air time, in a country where media are tightly controlled, and state-of-emergency decrees have limited the freedom of assembly and speech.

“The restrictions we have seen on fundamental freedoms have had an impact on these elections,” Ignacio Sanchez Amor, the leader of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe election monitoring mission, said in a statement. He noted that two observers were prevented from entering Turkey. “I expected more cooperation from the Turkish authorities on such an important election observation mission, as we always act in good faith and in Turkey’s best interest.”

The president’s first urgent task after the election is to try to prop up the economy, William Hale, a professor emeritus of Turkish politics at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, told WhoWhatWhy. He added that there are early signs Erdogan may listen to his more experienced economic advisors and lessen his meddling in Central Bank policy, which has precipitated the fall of the Turkish lira by almost 20 percent against the dollar since the start of the year.

More controversial is the issue of the state of emergency, in place now for almost two years after a failed military coup attempt in July 2016. Erdogan had promised to lift the emergency decrees after the election, but his party now lost its majority in parliament, forcing him to rely on his ultranationalist ally MHP, also known as the Nationalist Movement Party, to pass laws and make official the power transfer. MHP opposes lifting the state of emergency.

When it comes to hopes for peace or for improved relations with the West, few have many. The MHP is a sworn enemy of the Kurds, who, by different estimates, make up between a sixth and a quarter of Turkey’s population of 80 million. The ultranationalist ally has cheered and spurred on the merciless military campaigns against Kurdish guerrillas that Erdogan has waged in Turkey as well as in Syria and Iraq in recent years, in a successful bid to rally nationalist sentiment behind him.

Kurdish militants in Syria are a key ally of the US in the war against Islamic State, and those campaigns have already severely strained Turkey’s relationship with NATO. Now Erdogan may have no option but to continue, even though he has seemingly accomplished his power grab.

“The notoriously anti-Kurdish MHP is king maker for AKP in parliament and has made it clear that it expects to play a role in policy,” Jenny White — a prominent Turkey analyst at Stockholm University — told WhoWhatWhy. “This means that AKP will keep on the path to war, not peace, with the Kurds, whether in Syria, Iraq or Turkey.”

Noting that, despite his success, his power base is eroding, critics also fear further crackdowns on what remains of Turkey’s democracy. Fresh from the voting booth, the country is already eyeing next year’s municipal elections, widely seen as a stepping stone toward meaningful opposition. (“Whoever wins Istanbul, wins Turkey,” Erdogan, a former Istanbul mayor, likes to say.)

“I think they will start a new wave of raids after the election now, against the few remaining independent media, and some leftist organizations, and some youth unions, etc.,” said Ozturan. “This is the first step they will take, I think, because they realize that right now, everyone is focusing on the municipal elections. So for six months, I think, they will start imposing even further pressure, but this is also going to reflect sadly on the economy.” The prospect of further unrest, experts warn, may further destabilize the US’s already frayed relationship with a key ally.

Shares