According to the most recent U.S. census, approximately 15 percent of all newlywed couples are interracial. More interracial relationships are also appearing in the media — on television, in film and in advertising.

These trends suggest that great strides have been made in the roughly 50 years since the Supreme Court struck down anti-miscegenation laws.

But as a psychologist who studies racial attitudes, I suspected that attitudes toward interracial couples may not be as positive as they seem. My previous work had provided some evidence of bias against interracial couples. But I wanted to know how widespread that bias really is.

What does each race think?

To answer this question, my collaborator James Rae and I recruited participants from throughout the U.S. to examine implicit and explicit attitudes toward black-white interracial couples.

Psychologists typically differentiate between explicit biases — which are controlled and deliberate — and implicit biases, which are automatically activated and tend to be difficult to control.

So someone who plainly states that people of different races shouldn’t be together would be demonstrating evidence of explicit bias. But someone who reflexively thinks that interracial couples would be less responsible tenants or more likely to default on a loan would be showing evidence of implicit bias.

In this case, we assessed explicit biases by simply asking participants how they felt about same-race and interracial couples.

We assessed implicit biases using something called the implicit association test, which requires participants to quickly categorize same-race and interracial couples with positive words, like “happiness” and “love,” and negative words, like “pain” and “war.” If it takes participants longer to categorize interracial couples with positive words, it’s evidence that they likely possess implicit biases against interracial couples.

In total, we recruited approximately 1,200 white people, over 250 black people and over 250 multiracial people to report their attitudes. We found that overall, white and black participants from across the U.S. showed statistically significant biases against interracial couples on both the implicit measure and the explicit measure.

In contrast, participants who identified as multiracial showed no evidence of bias against interracial couples on either measure.

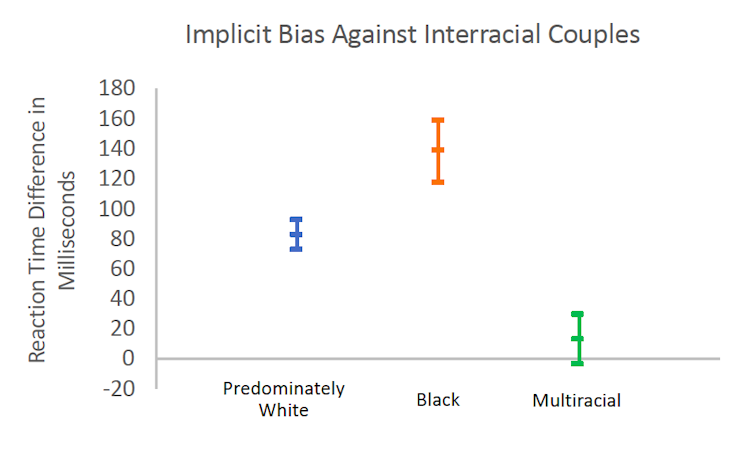

The figure below shows the results from the implicit association test. The lines indicate the average discrepancy in the length of time it took participants to associate interracial couples with positive words, when compared to associating same-race couples with positive words. Notice that for multiracial participants, this average discrepancy overlaps with zero, which indicates a lack of bias.

Allison Skinner and James Rae, Author provided

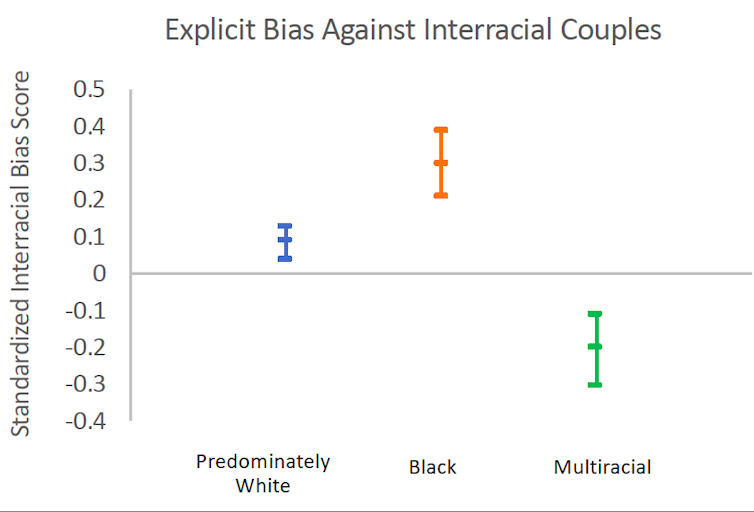

Next is a figure detailing the results from the explicit bias test, with lines measuring average levels of explicit bias against interracial couples. Positive values indicate bias against interracial couples, while negative values indicate bias in favor of interracial couples. Note that multiracial participants actually show a bias in favor of interracial couples.

Allison Skinner and James Rae, Author provided

Although we cannot know for sure from our data, we believe that the lack of bias observed among multiracial participants may stem from the fact that they’re the product of an interracial relationship. Then there’s the reality of their own romantic relationships. Multiracial people have few romantic options that would not constitute an interracial relationship: Over 87 percent of multiracial participants in our sample reported having dated interracially.

Predicting bias

We also wanted to know what might predict bias against interracial couples.

We anticipated that those who had previously been in an interracial romantic relationship — or were currently involved in one — would hold more positive attitudes.

For both white and black participants, this is precisely what we found. There was one catch: Black participants who had previously been in an interracial relationship were just as likely to harbor explicit biases as those who hadn’t been in one.

Next, we wanted to test whether having close contact — in other words, spending quality time with interracial couples — was associated with positive attitudes toward interracial couples. Psychological evidence has shown that contact with members of other groups tends to reduce intergroup biases.

To get at this, we asked participants questions about how many interracial couples they knew and how much time they spent with them. We found that across all three racial groups, more interpersonal contact with interracial couples meant more positive implicit and explicit attitudes toward interracial couples.

Finally, we examined whether just being exposed to interracial couples — such as seeing them around in your community — would be associated with more positive attitudes toward interracial couples. Some have argued that exposure to interracial and other “mixed status” couples can serve as a catalyst to reduce biases.

Our results, however, showed no evidence of this.

In general, participants who reported more exposure to interracial couples in their local community reported no less bias than those who reported very little exposure to interracial couples. In fact, among multiracial participants, those who reported more exposure to interracial couples in their local community actually reported more explicit bias against interracial couples than those with less exposure.

The outlook for the future

According to polling data, only a small percentage of people in the U.S. — 9 percent — say that the rise in interracial marriage is a bad thing.

Yet our findings indicate that most in the U.S. harbor both implicit and explicit biases against interracial couples. These biases were quite robust, showing up among those who had had close personal contact with interracial couples and even some who had once been involved in interracial romantic relationships.

The only ones who didn’t show biases against interracial couples were multiracial people.

Nonetheless, in 2015, 14 percent of all babies born nationwide were mixed race or mixed ethnicity — nearly triple the rate in 1980. In Hawaii, the rate is 44 percent. So despite the persistence of bias against interracial couples, the number of multiracial people in the U.S. will only continue to grow — which bodes well for interracial couples.

Allison Skinner, Psychology Researcher, Northwestern University