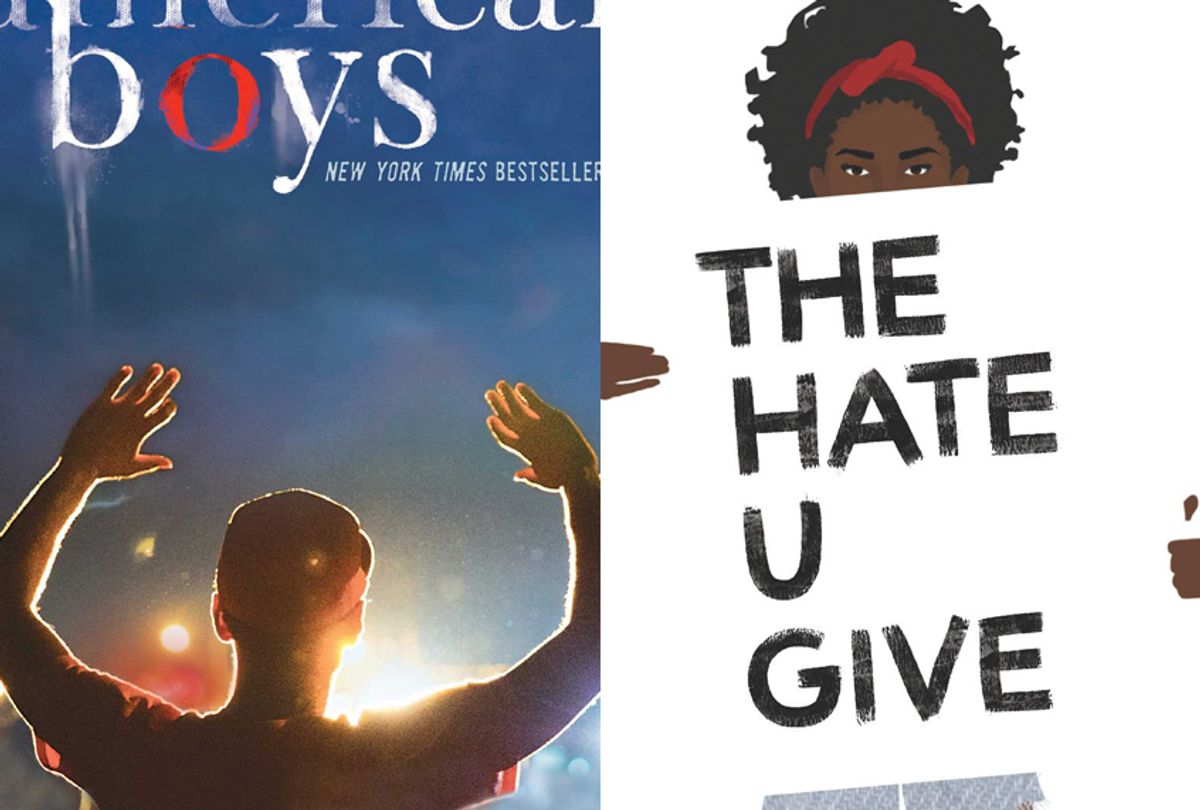

Two award winning, bestselling young adult books are the center of controversy in Charleston County, South Carolina. Police have spoken out against the inclusion of "The Hate U Give" by Angie Thomas and "All American Boys" by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely on a summer reading list for Wando High School's English I class, raising concerns about police involvement in school curricula.

Both books explore themes of racism and police brutality, issues that are relevant to the lives of many youth and young adults, especially in black communities. According to the president of the Fraternal Order of Police Tri-County Lodge #3, "The Hate U Give" and "All American Boys" encourage "distrust of police" and the law enforcement union is seeking the removal of the two texts from the list.

"Whether it be through social media, whether it be through text message, whether it be phone calls, we've received an influx of tremendous outrage at the selections by this reading list," lodge president Jon Blackmon told local news channel News 2. "Freshmen, they're at the age where their interactions with law enforcement have been very minimal. They're not driving yet, they haven't been stopped for speeding, they don't have these type of interactions. This is putting in their minds, it's almost an indoctrination of distrust of police and we've got to put a stop to that."

He added, "There are other socio-economic topics that are available and they want to focus half of their effort on negativity towards the police? That seems odd to me."

Neither of the books are mandatory reading — the list includes eight books, and students only have to select two.

The response from the FOP, one of the largest police organizations in the country, raises concerns for school librarians about censorship and for members of the Charleston community. After all, this is the same city where white police officer Michael Slager fired eight shots at Walter Scott while he ran away, striking him five times in total and three times in the back, in 2015. It was a crime so blatant the officer was actually prosecuted — and convicted, with a 20-year sentence, for an on-duty shooting. That same year, white supremacist Dylann Roof walked into a Charleston church and massacred nine black parishioners, and police bought Roof a Burger King meal after they apprehended him.

Poet Marjory Wentworth teaches a college course on banned books at The Art Institute of Charleston. She told Salon that "these are exactly the kinds of books we need to be reading and the conversations we need to be having."

"Keeping them out of the hands of kids is a dangerous activity," said Wentworth.

Wentworth added that Blackmon's depiction of the two books as anti-police is a miscategorization. "The idea that this is a one-dimensional, anti-police book, just, it's inaccurate," Wentworth said.

"The Hate U Give" was inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement and tells the story of a teenage girl who sees the police shoot her unarmed best friend. Beyond the nuanced exploration of police brutality and its wide-reaching effects on a community, the protagonist's uncle is a black police officer and a positive influence in her life. The acclaimed bestseller has been turned into a movie, which premieres this fall.

"All American Boys" follows a teenage boy trying to grapple with the aftermath following an incident with the police where he is falsely accused of shoplifting and then brutally beaten by a police officer.

"Especially in Charleston County, look at what we've lived through there," Wentworth said. For young people, she said, "books are a great way to process and make sense of something that they don't understand."

South Carolina high school librarian Tamara Cox agreed. She emphasized to Salon that high school students are engaged and interested in the issues that are center stage in the nation, "and that’s what they want to see reflected in what they read."

"That helps them figure out what they think and helps them figure out their place in the world," said Cox. "Reading is just a powerful way to engage in the world that the kids are surrounded by already. You're really not protecting them by limiting what they can read because they're already in the middle of it."

She added that usually when adults challenge books that kids are reading in school, they haven't actually read them in full and they're judging the cover, a blurb, or an excerpt taken out of context. Cox said that the police union's framings of the books as "negativity towards the police" makes her assume they have not read them either.

School librarian and South Carolina Association of School Librarians president Heather Thore agrees.

"I encourage everyone who is worried about these books to actually read them, and even talk to teens about their impressions of the books," Thore wrote in a statement to Salon.

Both veteran librarians wondered why the police union's first reaction was to ban or to remove the books, rather than read and discuss them with the students.

"Neither book is anti-police. Sadly, we do live in a world where police brutality is a thing," Thore continued. "Unfortunately, there are some people who have experienced police brutality, and their world needs to be shown through literature, as well as those who have the best experience with law enforcement."

Blackmon's stance that literature or art can sour young people on the police is also misguided, according to author Mychal Denzel Smith.

"The idea that people are planting this idea of the police in children's heads as opposed to children observing the world and seeing police for who they are, what they actually do, is completely off-base," said Smith, author of the New York Times Bestseller "Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching."

"[Black] children have had interactions with the police, whether the police want to admit to this or not. It starts way earlier than when they can drive," he continued. "They know family members who have been arrested. They've been in cars that have been stopped, if they weren't driving them themselves. All of this stuff is in the lives of black children."

When Blackmon says teenagers might not have first hand experience with the police before reading these books, he might be thinking of white teens instead. But when 12-year-old Tamir Rice is gunned down by an officer, when 17-year-old Antwon Rose is shot while running away and when 18-year-old Mike Brown is described as "Hulk Hogan," it shows how, so often, police don't see or treat black children as the kids they are.

"So they do have interactions with the police. On the basis of that alone that they are presumed to be bigger, older, and larger threats than what they are. What we're dealing with is an organization of police officers that are trying to protect their reputation of mythology around police that is divorced from reality," Smith said. "That's the problem here is that the police are more interested in upholding the myth than they are in changing the reality."

Much like the conversation of separating and detaining immigrant children away from their parents has warped into a debate over it was rude to deny press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders service and other values of civility, the controversy in Charleston County dims the spotlight on police brutality and misconduct, focusing instead on the young adult authors' responses to such violence. Rather than focusing on accountability from the source and perpetrators of state violence, the conversation shifts to debating the legitimacy of people's reactions.

Wando High School Principal Dr. Sherry Eppelsheimer wrote in a statement to News 2 that "A 'Request for Reconsideration of Instruction Materials' form has been submitted and the school and District will follow the procedures outlined in Policy IJKAA-R in connection with the reconsideration request."

The policy instructs that a committee be formed to review the material and to hear from the parent who complained, the assigning teacher and other experts. A recommendation is provided to the Superintendent, who can accept or reject it. A final decision is made by the Board of Trustees.

So the verdict is still out on if Wando High School students will have the opportunity to dissect poignant, relevant literature like "The Hate U Give" and "All American Boys" as a class, which would be a vital opportunity for at least some students to see themselves represented and their experiences reflected in school curricula.

With public school resources at a premium, the police union has in a way already won part of its battle — precious time must be devoted now to reviewing the the books' inclusion rather than on other programs or initiatives.

In this vein, Blackmon's remarks signal the lack of interest of the local FOP in reckoning with the murder of Walter Scott and the racist bloodshed by Roof, as he seeks to discredit the art and experiences of an entire population of people impacted by police brutality. But Thore wonders if those students deserve to see themselves represented in literature, too.

"There are so many books available where police are the heroes, but is every police officer a hero?" she questioned. "Bottom line, our young readers (especially teens who often lose interest in reading) need to have access to diverse books. . . As school librarians, it is our job to give students this access, to provide the mirrors and windows for every student."

Shares