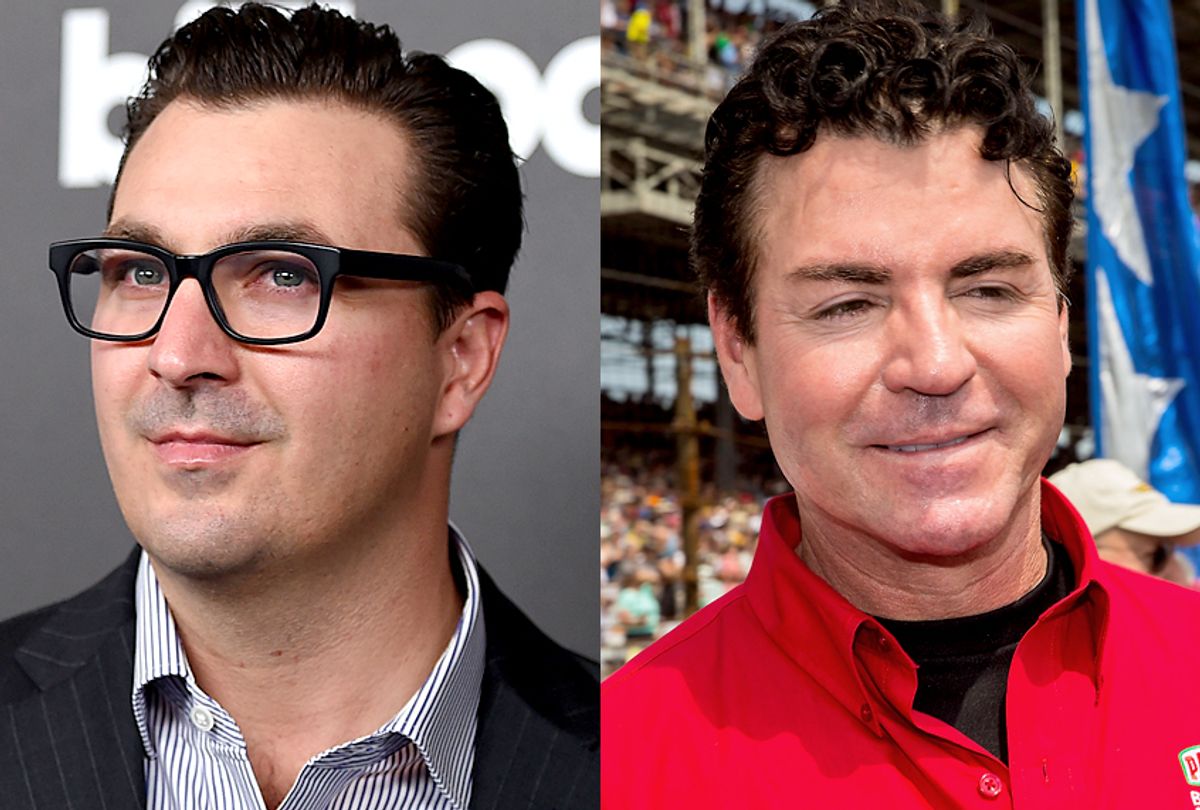

Gee, what a big week for men moving on from their jobs! On Wednesday, Valence Media announced that chief executive of Hollywood Reporter-Billboard Media Group John Amato was stepping down from his position, two months after The Daily Beast reported that Amato had been squelching stories on the recent sexual harassment claims against Republic Records' ex-president Charlie Walk. Meanwhile, Cook County Forest Preserve District police officer Patrick Connor, who went viral when footage of him seeming to do nothing while a woman wearing a Puerto Rico shirt was verbally harassed, resigned from his post. And Papa John's founder John Schnatter also resigned as chairman of his company's board after a Forbes story reported that he'd remarked that "Colonel Sanders called blacks [the n-word]" during a call with a marketing agency.

Getting to quietly slink off from your job after your behavior — or lack of it — has been exposed is becoming a familiar theme lately. The offenders are often men, though the recently resigned woman known as Permit Patty is certainly of note. The people calling them out are frequently women, and frequently women of color. And the aspect of this story that keeps crystalizing in my mind is all the monumental effort — the deluge of compelling evidence, the glaring public shaming — that it takes to get one of these guys to go away. Not even be fired! Just to get them to say, "Well, I guess gotta fly right and go home now."

Imagine having the privileges of being the founder and chairman of a successful pizza chain. You think you'd have the social intelligence to have an unexpressed thought or two, not to have to weigh in on NFL players taking a stance on racial injustice. You'd think after a public debacle over it, you'd learn something. You wouldn't have to, as John Schnatter did, literally use a marketing agency named Laundry Service for what Forbes this week called a "role-playing exercise for Schnatter . . . to prevent future public-relations snafus." And you surely wouldn't then casually reference a racial slur and then recount the days when "people used to drag African-Americans from trucks until they died."

Yet somehow Schnatter made it to the age of 56 without learning how to have a business conversation that doesn't offend people — even after Netflix PR chief Jonathan Friedland was canned under similar circumstances just last month.

You might also think that if you were the head of a large media group, you would know — as one staffer in John Amato's company told The Daily Beast — that, "It’s a pretty brazen act of mansplaining to decide what’s newsworthy and what’s not. It's not smart to tell reporters, many of whom are female, what is valuable to report and not to report in #MeToo." But here we are.

Here we are, where it takes dozens of individuals telling the same story of abuse or harassment for it to become a news story. Here we are, where it takes a deluge of public exposure for there to be consequences for bullying, racist or violent behavior, where the only way to get action is to drag the story, kicking and screaming, into the daylight.

I think about the phrase "emotional labor" all the time lately. I think about the daily effort that goes into fixing other people's screwups, pointing out problems, asking politely for things to be done or undone or changed or improved. I think about how routinely many of us find ourselves faced with three crappy choices — to cajole, beg and demand something get done; to ignore the problem as it continues; or to find a way to fix it ourselves. I assure you all three are stressful and time-consuming. I think of the psychic toll the moral laziness and learned helplessness of others truly takes on everybody else.

In Gemma Hartley's galvanizing 2017 essay, "Women Aren't Nags—We're Just Fed Up," she was speaking specifically of family dynamics when she wrote on women and "the subject of all the behind-the-scenes work they do," and how "it’s frustrating to be saddled with all of these responsibilities, no one to acknowledge the work you are doing, and no way to change it without a major confrontation." But this is a workplace issue and a political issue as well as an intimate one. Because it's the contract we didn't sign but find ourselves bound to anyway — that crappy people are going to keep right on doing crappy things until we do the herculean work of changing them or replacing them. Because it's the tacit expectation that unless we're providing a specific set of actions that need to be taken, action will not be taken.

Do we actually have to have thousands of people on social media point out that a cop should intervene when a woman is being harassed in park? When did that become everybody else's job? Whether it's a trail of dirty laundry left on a bedroom floor or a media executive who'd apparently rather protect a bro than publish newsworthy information or an administration that seems stoked to take away your bodily autonomy, the job of keeping everything from not going completely off the rails — or bringing it all back when it does — is relentless. And it comes at the expense of all the stuff we'd frankly be rather be doing.

Nearly every time some incompetent or toxic individual is forced to acknowledge a mess of his own creation, it comes with a shrugging plea of ignorance. Louis C.K., a 50-year-old man, says, "What I learned later in life, too late, is that when you have power over another person, asking them to look at your dick isn’t a question. It’s a predicament for them." Really? You had to learn that? Matt Lauer says, after being fired, "I realize the depth of the damage and disappointment I have left behind at home and at NBC." Oh, now you do? The implication is clear, and I'd wager it's one you've heard in your own work and marital fights: "How am I supposed to know unless you tell me?" To which I ask, do you think everybody else got a secret memo you weren't cc:ed on? Or do you think some people are just born with a native talent for remembering birthdays or not sexually harassing their coworkers? And why are you punting the job of educating you back to us? The infantilized BS we endure at the hands of incompetent and destructive is ceaseless.

The rest of us, those without the privileges of a secure job or wealth or fame, have to figure these things out early. Not everybody does, of course. But a great many people know by the time they reach adulthood how to clean up our messes, how to treat other people in a way that's not just respectful but actually conciliatory, because we have to. So we do the boring, grueling, thankless work, because we have yet to run out of selfish d-bags who refuse to do the right thing until they are forced to. But we have carried you guys for millennia now and our backs are sore. We got the same manual on how to behave appropriately that you did, except we read it. And now, I swear, the emotional labor force is ready to go on strike.

Shares