Is the Democratic Party moving too far left, too fast? With Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez now a national figure, less than a month after her surprise primary victory over incumbent Rep. Joe Crowley, D-N.Y., the question is everywhere.

Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont nearly seized the Democratic presidential nomination from Hillary Clinton in 2016, and may run again in 2020. Many Democrats see Ocasio-Cortez’s primary victory as a leading indicator of a grassroots rebellion against the party’s middle-road establishment. When candidates like those — or others interviewed in a New York Times feature this weekend — discuss issues like persistent poverty, lack of economic opportunity and the sense that our political system is more beholden to big businesses than ordinary people, they speak to longstanding tensions and grievances within the Democratic coalition.

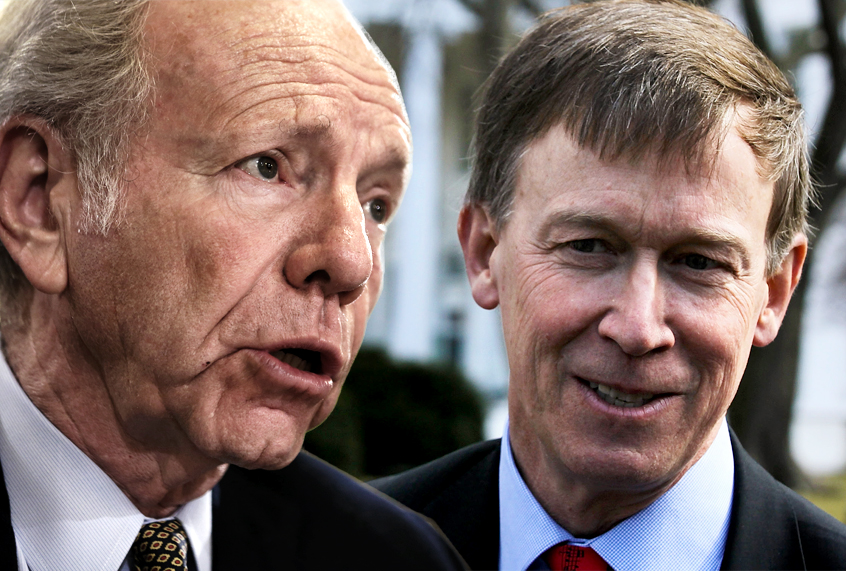

At the same time, many Democrats are uncomfortable with this apparent left turn. For the party to be politically viable in the future, it must develop an approach to governing that can win as many voters as possible, and that can work not only in theory, but in practice. One standard-bearer for this view is former Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, who recently published a Wall Street journal op-ed urging voters in Ocasio-Cortez’s district to re-elect Crowley on a third-party line, despite his decisive defeat in the Democratic primary. Ocasio-Cortez advocates policies “far from the mainstream,” Lieberman wrote, and electing her “would make it harder for Congress to stop fighting and start fixing problems”:

Ms. Ocasio-Cortez is a proud member of the Democratic Socialists of America, whose platform, like hers, is more Socialist than Democratic. Her dreams of new federal spending would bankrupt the country or require very large tax increases, including on the working class. Her approach foresees government ownership of many private companies, which would decimate the economy and put millions out of work.

Ms. Ocasio-Cortez didn’t speak much about foreign policy during the primary, but when she did, it was from the DSA policy book — meaning support for socialist governments, even if they are dictatorial and corrupt (Venezuela), opposition to American leadership in the world, even to alleviate humanitarian disasters (Syria), and reflexive criticism of one of America’s great democratic allies (Israel).

She has received the most attention for calling to “Abolish ICE,” Immigration and Customs Enforcement. This makes no sense unless you no longer want any rules on immigration or customs to be enforced. I have not heard anyone say that. Nonetheless, at least three credible candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination rushed to endorse Ms. Ocasio-Cortez’s position.

That is not likely to work: While it’s true that Crowley’s name will be on the ballot, he has no plans to campaign against Ocasio-Cortez in the general election. Lieberman has some expertise in the topic, however: When he lost the Democratic nomination in Connecticut in 2006, he left the party and was re-elected to the Senate on a third-party line, serving his next term as an independent.

Lieberman’s Wall Street Journal article appeared after my recent conversation with him about the leftward drift of the Democratic Party, but the views he expressed were certainly similar.

“As much as anybody is able to predict anything in our politics these days, I believe that a strong leftward movement in the Democratic Party is a movement in the direction of defeat and minority status,” Lieberman told Salon. “This is an old story that played out over the decades. The inspirational figure of my early life was John F. Kennedy. That was true of a lot of people of my generation. To state a complicated matter simplistically, Kennedy represented what the Democratic Party was, which was progressive on domestic policy and principled and muscular on foreign and defense policy. He believed in regulatory government, but he was pro-business, he was pro-growth. I think that combination still makes a lot of sense to me.”

I also spoke recently with Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper, who has been mentioned as a possible 2020 presidential candidate. He said he was a “maybe” in terms of seeking the Democratic nomination, but dismissed all rumors that me might run on a third-party ticket with Ohio Gov. John Kasich. Like Lieberman, Hickenlooper has a reputation for being far more moderate on policy than is currently popular in his party. When he spoke about health care reform in his state, he sounded a bit like Barack Obama in 2010, when many progressives attacked him for the perceived weakness of the Affordable Care Act.

“I’ve been supporting and we’ve been working towards universal health care coverage in the State of Colorado system,” Hickenlooper told Salon. “The day I got elected, I stood firm and have always stood firm that health care should not be a privilege, it should be a right.” He says he doesn’t see proponents of a single-payer system as “extreme,” adding, “There’s no question that single payer is going to be more cost effective.”

He simply doesn’t believe that’s an achievable goal. “I just think that we can’t get there,” Hickenlooper said. “I don’t think we can get to universal coverage as quickly if we try to fight that battle now. I think that the imperative now should be to make sure everyone’s covered, that we should get there first.”

Hickenlooper also said that as the governor of a Western state, he has the advantage of working within a political culture that encourages and rewards bipartisan collaboration.

“I trace it back all the way to when the West was first settled and it was somewhat inhospitable in those early days,” Hickenlooper said. “In the early 19th century people had to work together. I mean, the wagon train was a great tool, that settled the West. On a wagon train, everybody’s got a role, right? One person’s cooking, one person’s hunting, one person’s cleaning. It was a really collaborative system.” Hickenlooper says that same ethos lingered in the political culture of the Rocky Mountain states all the way into the 21st century.

“It’s very rare that you persuade someone to change their opinion about something by just telling them why they’re wrong,” Hickenlooper reflected. “The best way to persuade anyone of anything is to listen harder.”

Will Marshall, the president and founder of the Progressive Policy Institute (an organization once known as the “idea mill” for President Bill Clinton), emphasized the need for Democrats to have a “big tent” approach that can reach out to people not only from diverse demographic backgrounds, but also diverse ideological perspectives.

“I think the imperative for Democrats is to nominate a candidate who can broaden the party’s base, not just energize it,” Marshall told Salon. “Obviously when you’re in the minority in Washington and most states, and only hold 16 governorships, you aren’t winning enough elections in enough places. Your most urgent challenge is to build new majorities and win more elections. Instead of fighting over ideology, you’ve got to choose a presidential nominee who can bring new voters into the fold and make the Democrats more competitive in the places we’ve been losing across the country.”

Marshall argues there is an excessive emphasis on ideological fealty among Democrats at times, as evidenced in the victory of Ocasio-Cortez over Crowley. He sees that as dangerous for the party, at least on the national level.

“I am de-emphasizing ideology because the Democrats’ challenge is to build a big tent coalition that can win anywhere in the country,” Marshall explained. “Our Building New Democratic Majorities event last week was a real show of strength for the pragmatic wing of the party. For every progressive that wins a primary race in a deep blue district, a pragmatic candidate wins a race on more competitive ground. And when we go into the presidential election, we’ll need a candidate that can expand the party’s appeal beyond our urban and coastal strongholds.”

Marshall’s point was reiterated by Lieberman. “As you look back, when we won in recent decades, it’s been from the center, it’s been as a center-left party,” Lieberman explained. “I’m thinking particularly of [Jimmy] Carter and [Bill] Clinton, but I would also argue, and probably more controversially, Obama.” Lieberman actually opposed Obama in 2008, endorsing John McCain.

“One of the reasons I supported Hillary Clinton strongly in 2016 was that I believed not only was she totally capable of being a very good president, but within the Democratic Party she might well be our last chance for a while to have a center-left party and not a left-left party. That’s the battle that’s going to be fought during the presidential primaries leading up to 2020.”

Many people from the progressive wing of the Democratic Party would likely raise two familiar arguments here: Bernie Sanders would have had a better chance of defeating Donald Trump than Hillary Clinton did, and that there’s no meaningful difference between Democratic moderates like Hickenlooper or Lieberman and mainstream Republicans.

How well Sanders would have done in a general election against Trump is not knowable. Individual polls may have shown Sanders outperforming Clinton against Trump, but it’s not clear how widely Sanders’ philosophy was understood among the general electorate. Clinton’s supposed scandals became defining issues of the campaign, but had Sanders been nominated, voters would have been bombarded with attack ads about his alleged radicalism.

This isn’t to say that Clinton was necessarily the best choice for the Democratic Party. I’ve argued, both recently and as far back as 2015, that former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley deserved to be taken more seriously. It certainly doesn’t mean that the Democratic Party shouldn’t reform its primary process. But it’s by no means self-evident that the primary lesson from 2016 is that Clinton was too moderate and that an authentic leftist like Sanders would have won.

The second argument, it is specious for an entirely different and more ominous reason. The modern Republican Party seems to have been hijacked by its more extreme elements — fewer and fewer conservatives come from the more moderate tradition of McCain or Mitt Romney, and more and more seem to be trying to out-Trump the president at every turn. One of the Trump movement’s chief rhetorical weapons is to claim that Republicans who argue for bipartisan compromise are weak-minded sellouts.

When progressives apply that same logic to Democrats who mostly agree with them on the issues — and there can be little doubt that Joe Crowley and John Hickenlooper have far more in common with Bernie Sanders than they do with virtually any contemporary Republican — they are guilty of the same error as the pro-Trump faction of the GOP. If we truly want to break out of our era of hyper-partisanship and build a government that works again, we must apply the same standards to both sides.