During the 1990s, legal assaults on the tobacco industry spawned the largest and most expensive civil litigation in U.S. history. Explosive revelations from secret internal documents and tobacco whistleblowers became front page news.

After decades of deception, cigarette makers were forced to admit the dangers and addictiveness of smoking. Sweeping settlements with state attorneys general totaling $246 billion placed marketing restrictions on the industry and, by driving up the price of cigarettes, accelerated a decline in smoking rates.

And then, more than a decade ago, tobacco litigation all but died — except in Florida.

Anti-tobacco lawsuits have flourished in the one state that has remained a dismal swamp for cigarette makers, thanks to a unique set of ground rules that have given sick smokers a leg up in bringing claims. Tobacco companies face more lawsuits in Florida than in all other states combined, observers say. In recent years, the companies have paid out close to $800 million in damage awards and settlements, according to records and a running tally by plaintiffs lawyers. They have spent tens of millions more on legal fees. The final bill will go much higher as cigarette makers still face nearly 3,000 pending claims, interviews and records show.

It’s all the legacy of an exceptional case that seemed beyond a long shot when it was filed nearly a quarter-century ago.

In 1994, Miami trial lawyer Stanley Rosenblatt and his law partner-wife Susan Rosenblatt sued leading cigarette makers on behalf of all Florida smokers who allegedly suffered disease or death because of their addiction to smoking. The class action case, Engle vs. Liggett Group, Inc., was named for lead plaintiff Howard Engle, a Miami Beach pediatrician and lifelong smoker.

In July, 2000, after a nearly two-year trial in Miami-Dade Circuit Court, jurors issued a jaw-dropping verdict, ordering cigarette makers to pay $144.8 billion in punitive damages to be distributed among class members. But after hard-fought appeals, the Florida Supreme Court in 2006 dissolved the class and tossed out the $144.8 billion award.

Yet in ruling that sick smokers must bring their claims individually, the court also decreed that individual trials were to be guided by certain facts favorable to plaintiffs that were established in the Engle case–namely, that nicotine is addictive; that smoking is a proven cause of a number of lethal diseases; and that cigarette makers sold a product they knew was unreasonably dangerous while conspiring to conceal information from the public. These ground rules gave plaintiff lawyers a head start in building successful cases and have made Florida ”a world unto itself,” said Charles Tauman, a Portland, Oregon, attorney and president of the Tobacco Trial Lawyers Association, a plaintiff lawyers group. “Every time a judge reads the jury instructions, it’s a tribute to the Rosenblatts,” he said.

Stanley Rosenblatt, who is retired from his law practice, did not respond to requests for comment. Officials of top cigarette makers Philip Morris USA and R.J. Reynolds also did not respond to calls and emails requesting interviews.

In the wake of the Florida high court’s ruling, about 8,000 so-called “Engle progeny” suits were filed on behalf of individual smokers against the makers of the brands they smoked.

In 2013, cigarette maker Liggett Group settled most of the claims against it for $110 million. And in 2015, Philip Morris USA, R.J. Reynolds and Lorillard Tobacco Co. — which since has been acquired by Reynolds — agreed to pay $100 million to settle 415 Engle cases pending in federal court.

As of mid-June, 315 cases had been tried, with plaintiffs winning 168, or 53 percent, according to a running tally by the tobacco trial lawyers group. The others ended in defense verdicts or mistrials, according to the group’s box score.

Juries have hit the tobacco companies with dozens of damage awards of $10 million or more, though the biggest judgments rarely have been paid in full due to appeals or post-trial settlements for lower amounts.

Notably, in 2014 a jury in Escambia County in the Florida Panhandle delivered a punitive damage verdict of $23.6 billion in the case of Cynthia Robinson v. R.J. Reynolds. But a Tallahassee appellate court vacated the award, citing prejudicial statements by the plaintiff’s lawyers, who the court said “denigrated defendants for contesting the very facts that they, as plaintiffs, are required by law to prove.” The case is heading for retrial.

With the huge backlog of cases — and trials moving at a rate of only 30 to 50 per year — there is a chance of many claims dying with plaintiffs or their elderly survivors before they can be tried.

It isn’t easy to secure a trial date, said Howard Acosta, a longtime tobacco plaintiffs lawyer from St. Petersburg, who has about 150 pending Engle cases. “It’s very time-consuming,” he said. “State courts have to set aside three-week dockets for these trials, and most judges will set aside only two or three a year.”

Joseph Rice of Motley Rice, a prominent South Carolina plaintiffs firm that has dozens of Engle cases, said their dispersal to courts throughout Florida plays to the tobacco companies’ business strategy of “slow-walking” the litigation.

But relatively few tobacco lawsuits even exist in other states. “There are still people who are sickened by tobacco and who die, but the missing ingredient is, they can’t find a lawyer who wants to take their case, for what are probably good business reasons,” Tauman said.

For one thing, tobacco companies generally won’t settle cases or pay judgments without exhausting lengthy appeals, so even when cases are successful it takes years for the lawyer to get paid. Moreover, since cigarettes have carried warning labels for 50 years and awareness of the danger is nearly universal, it’s hard for smokers to argue that they didn’t know the risks.

But in Florida, tobacco cases still are heard in courtrooms all over the state. Eulalia Lopez v. R.J. Reynolds was recently tried in the Miami-Dade County Courthouse, where the original Engle trial commandeered a spacious courtroom.

The Lopez trial was held in a cramped courtroom big enough for only about two dozen visitors, the six-person jury and two alternates, along with oversized boxes of depositions and medical records. In the gallery were law firm interns, Lopez family members and a videographer from Courtroom View Network, a subscriber video service that streamed the proceedings, as it does many tobacco trials in Florida.

The case was atypical in some ways. Auto mechanic Juan Lopez died of lung cancer in 1994 at the age of 52, leaving his 41-year-old wife, Eulalia, to raise two young sons. From the early 1980s until his death in 1994, his cigarette of choice was Winston 100s, an R.J. Reynolds brand.

The complications were that Lopez, a native of Cuba, was already a heavy smoker when he fled to the U.S. in 1979. At some point he was also exposed to asbestos, another carcinogen, and lawyers and expert witnesses clashed over what actually killed him.

On June 6, after a scant two hours of deliberations, the jury returned a verdict for the defense.

For plaintiff attorney Eric Rosen, it was the first loss in seven tobacco trials. A week later, he seemed disappointed but undaunted. “We do plan to appeal at this point,” he said.

Rosen, 37, said he became intrigued with tobacco cases during his second year of law school after happening on a 1984 book called “Trial Lawyer,” by Stanley Rosenblatt.

Rosen said he expects to litigate tobacco cases for the foreseeable future. “To me these are the best cases to represent people and go up against an industry that has just completely disregarded human life and consumer safety,” he said. “The companies just look at their bottom line at the expense of consumers who didn’t really understand what they were getting into.”

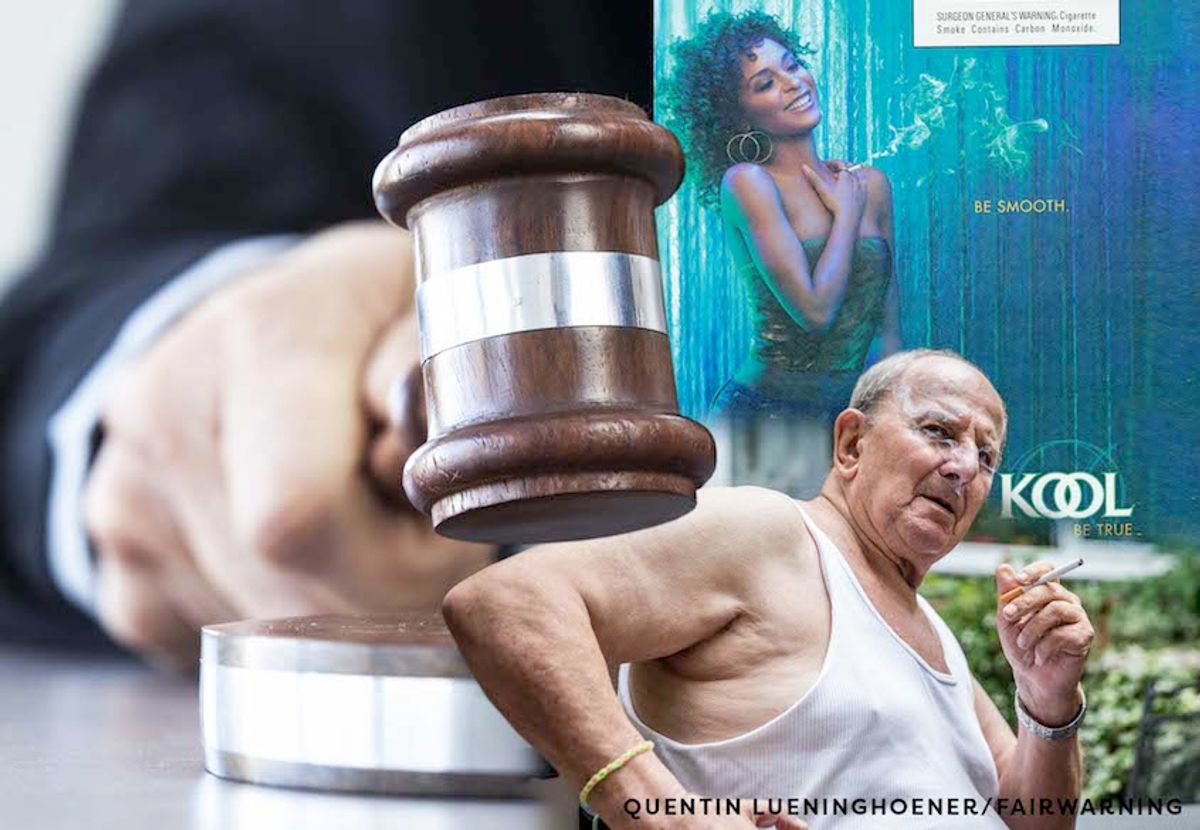

Kool ad courtesy of Stanford Research Into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising (tobacco.stanford.edu)

Shares